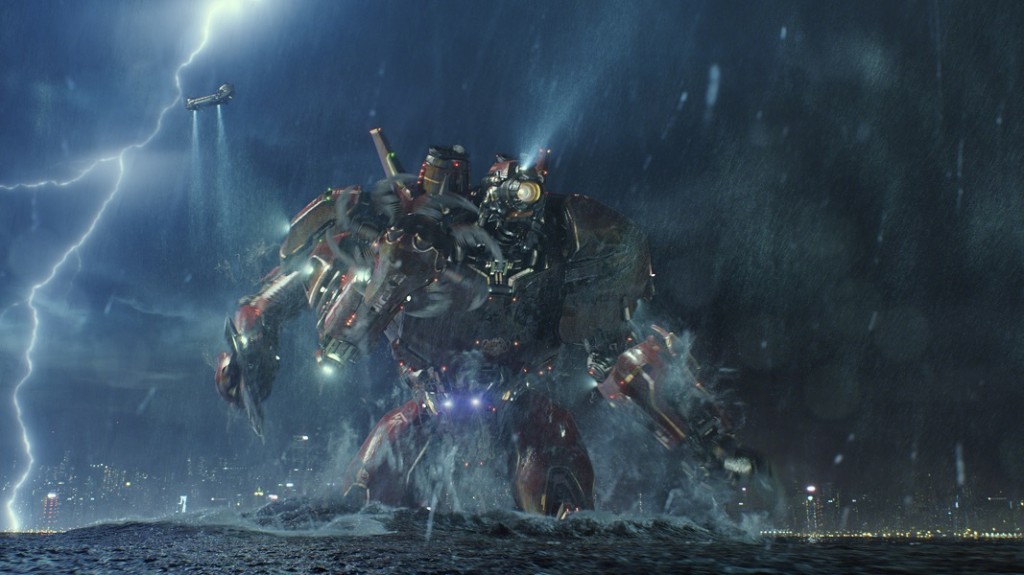

Two-thirds of the way through Pacific Rim — just after an epic battle in, around, and ultimately over Hong Kong that’s one of the best-choreographed setpieces of cinematic SF mayhem I have ever witnessed — I took advantage of a lull in the storytelling to run to the restroom. In the air-conditioned chill of the multiplex the lobby with its concession counters and videogames seemed weirdly cramped and claustrophobic, a doll’s-house version of itself I’d entered after accidentally stumbling into the path of a shink-ray, and I realized for the first time that Guillermo del Toro’s movie had done a phenomenological number on me, retuning my senses to the scale of the very, very big and rendering the world outside the theater, by contrast, quaintly toylike.

I suspect that much of PR’s power, not to mention its puppy-dog, puppy-dumb charm, lies in just this scalar play. The cinematography has a way of making you crane your gaze upwards even in shots that don’t feature those lumbering, looming mechas and kaiju. The movie recalls the pleasures of playing with LEGO, model kits, action figures, even plain old Matchbox Cars, taking pieces of the real (or made-up) world and shrinking them down to something you can hold in your hand — and, just as importantly, look up at. As the father of a two-year-old, I often find myself laying on the floor, my eyes situated inches off the carpet and so near the plastic dump trucks, excavators, and fire engines in my son’s fleet that I have to take my glasses off to properly focus on them. At this proximity, toys regain some of their large-scale referent’s visual impact without ever quite giving up their smallness: the effect is a superimposition of slightly dissonant realities, or in the words of my friend Randy (with whom I saw Pacific Rim) a “sized” version of the uncanny valley.

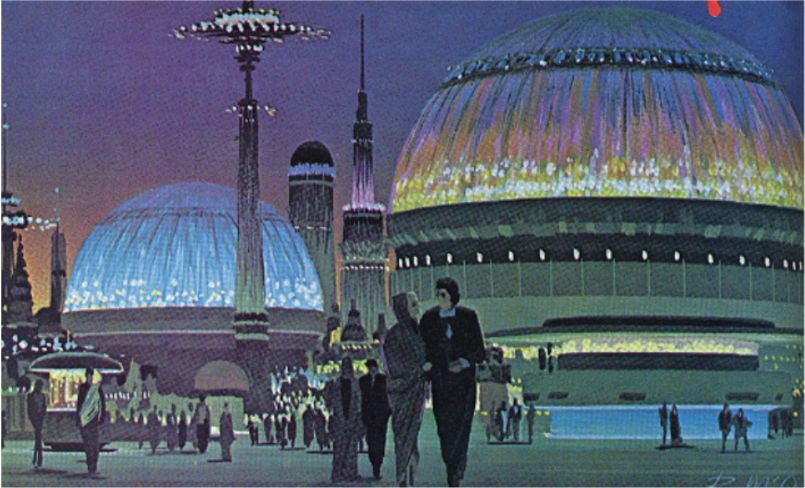

This scalar unheimlich is clearly on the culture’s mind lately, literalized — iconized? — in tilt-shift photography, which takes full-sized scenes and optically transforms them into images that look like dioramas or models. A subset of the larger (no pun intended) practice of miniature faking, tilt-shift updates Walter Benjamin’s concept of the optical unconscious for the networked antheap of contemporary digital and social media, in which nothing remains unconscious (or unspoken or unexplored) for long but instead swims to prominence through an endless churn of collective creation, commentary, and sharing. Within the ramifying viralities of Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, Reddit, and 4chan, in which memes boil reality into existence like so much quantum foam, the fusion of lens-perception and human vision — what the formalist Soviet pioneers called the kino-eye — becomes just another Instagram filter:

The giant robots fighting giant monsters in Pacific Rim, of course, are toyetic in a more traditional sense: where tilt-shift turns the world into a miniature, PR uses miniatures to make a world, because that is what cinematic special effects do. The story’s flimsy romance, between Raleigh Beckett (Charlie Hunnam) and Mako Mori (Rinko Kikuchi) makes more sense when viewed as a symptomatic expression of the national and generic tropes the movie is attempting to marry: the mind-meldly “drift” at the production level fuses traditions of Japanese rubber-monster movies like Gojiru and anime like Neon Genesis Evangelion with a visual-effects infrastructure which, while a global enterprise, draws its guiding spirit (the human essence inside its mechanical body, if you will) from Industrial Light and Magic and the decades of American fantasy and SF filmmaking that led to our current era of brobdingnagian blockbusters.

Pacific Rim succeeds handsomely in channeling those historical and generic traces, paying homage to the late great Ray Harryhausen along the way, but evidently its mission of magnifying 50’s-era monster movies to 21st-century technospectacle was an indulgence of giantizing impulses unsuited to U.S. audiences at least; in its opening weekend, PR was trounced by Grown Ups 2 and Despicable Me 2, comedies offering membership in a franchise where PR could offer only membership in a family. The dismay of fans, who rightly recognize Pacific Rim as among the best of the summer season and likely deserving of a place in the pantheon of revered SF films with long ancillary afterlives, should remind us of other scalar disjunctions in play: for all their power and reach (see: the just-concluded San Diego Comic Con), fans remain a subculture, their beloved visions, no matter how expansive, dwarfed by the relentless output of a mainstream-oriented culture industry.