Sad news: Ben Chapman, who played the Creature from the Black Lagoon in the 1954 film of the same name, is dead.

Chapman’s death, while no less tragic, hits me a little differently than the passing of William Tuttle, whom I wrote about last August. While Tuttle contributed to hundreds of films, Chapman played just one role in one movie — and that uncredited at the time. While Tuttle worked behind the scenes, Chapman performed in front of the camera. And while Tuttle designed and applied makeup and prosthetics that others wore, Chapman was literally the man in the suit: a full-body sheath made of foam rubber, a headpiece fringed with pulsating gills, and two webbed gloves tipped with fearsome claws.

In this sense, we might think of Chapman as occupying a nodal point in the circuit of special effects manufacture precisely opposite that of the costume’s “creator.” Somebody else designed the thing; all Chapman did was inhabit it. Indeed, Chapman’s contribution subdivides and apparently dissipates the more closely we examine it, scattering into a shadowy network of elided labor and thwarted fame. He was not, for example, the only person to play the Creature. Ricou Browning wore the suit for underwater sequences, while Chapman did the bits on land. (Browning returned for the water scenes in sequels Revenge of the Creature [1955] and The Creature Walks Among Us [1956]; in these films the Creature-on-land was played by Tom Hennesy and Don Megowan respectively.) Even the suit’s original designer is in question, credited for many years to veteran makeup artist Bud Westmore, but recently recuperated as the work of Milicent Patrick.

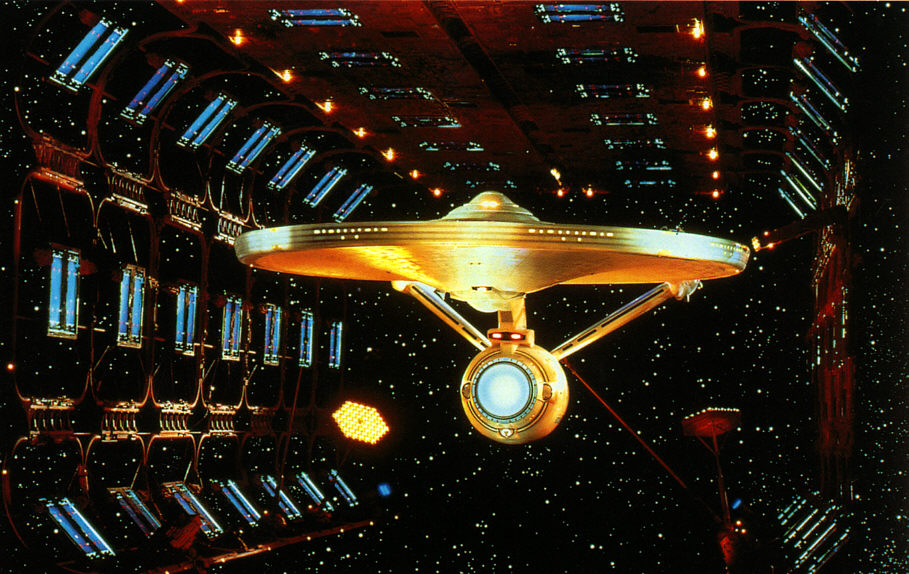

Yet amid the thicket of Hollywood’s ramified pasts, Chapman and the suit he wore are fused in my memory as well as the collective memory of horror and science fiction fans. To some extent this is due to the first Creature‘s place at the overlap of several important genre histories. It was a cornerstone of the grand 1950s wave of cinematic SF that includes The Thing from Another World (1951), The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), War of the Worlds (1953), Them (1954), Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), Earth Versus the Flying Saucers (1956), The Blob (1958), and — a personal favorite and source of this blog’s signature image — Forbidden Planet (1956). Moreover, Creature was directed by Jack Arnold, who also helmed the classics It Came From Outer Space (1953), This Island Earth (1955), and The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957).

Not all of these films are of equal caliber, certainly. They run the gamut from cerebral “message” films to drive-in shockers, a continuum on which Creature probably registers toward the window-mounted-speakers end. Befitting its status as an early Jaws, Creature was released in 3D. As a kid, I was lucky enough to see one of these ghosty red-and-green prints at a screening on the University of Michigan campus; the headache induced by those plastic glasses is inseparable from the excitement of seeing claws jutting out of a petrified wall in one of the film’s opening images.

But the fascination of Creature (the movie) and Creature (the monster) outlasted their tricked-up 3D and their genre boomlet, surviving as only an icon can throughout many replayings on TV, VCR, and DVD. Ben Chapman built a career out of his few minutes on screen, appearing at conventions, giving interviews, and running a website whose very title — www.the-reelgillman.com — insists on the singular authenticity of his performance. Like the suit he wore, a neglected piece of film flotsam rediscovered by a janitor and ultimately purchased by Forrest J. Ackerman of Famous Monsters, Chapman physically anchored a diffuse cloud of memories and fantasies, concretizing a point in time and space where Creature from the Black Lagoon “really happened.”

Not just an icon, then, but an index: evidentiary proof of a world existing simultaneously before the camera and within our imaginations, and hence a junction point between virtual and real, dream and daylight, forgotten and retrieved, submarine and dry land.