How does the old joke go? “What a terrible restaurant — the food sucks, and such small portions!” That seems to be the way a lot of people feel about AMC’s The Walking Dead: it’s an endless source of disappointment as well as the best damn zombie show on television.

How does the old joke go? “What a terrible restaurant — the food sucks, and such small portions!” That seems to be the way a lot of people feel about AMC’s The Walking Dead: it’s an endless source of disappointment as well as the best damn zombie show on television.

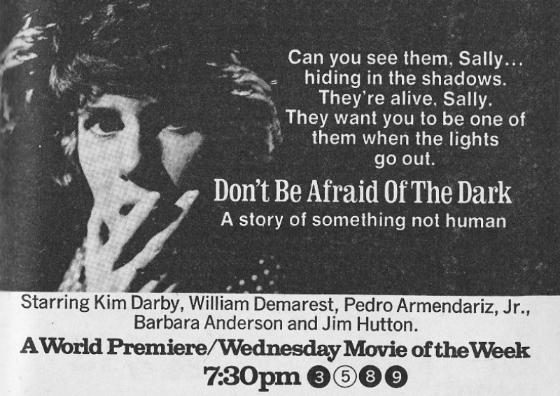

Not that there’s much competition. Contemporary TV horror is a small playing field, nothing like the heyday of the 1970s, when Night Gallery, Kolchak, Ghost Story, and telefilms like Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark fed home audiences a plentiful stream of dark and disturbing content, “channeling” a boom in horror cinema that began with demonic-possession blockbuster The Exorcist and morphed late in the decade, via Halloween and Friday the 13th, into the slasher genre. The only real competition for TWD is American Horror Story, a series whose unpleasantness is so expertly-wrought that I couldn’t make it past the third episode. Apart from this and an endless supply of genre-debasing quasi-reality shows on SyFy a la Paranormal Witness, there’s simply not a lot to choose from, and for this reason alone, The Walking Dead is far, far better than it needs to be.

But it’s still a frustrating show: like its zombies, slow-moving and unsure of its goals. (The guys at Penny Arcade, it should be pointed out, hold the opposite interpretation.) Following a phenomenal pilot episode that ended on one of the best cliffhangers I’ve seen since the closing shot of Best of Both Worlds, Part 1, the first season burned through four tense episodes, only to close with an implausible, shoehorned finale set in CDC control center. Season two, at twice the length, has moved at half the speed, and while I enjoyed the thoughtful pace of life at Herschel’s farm, I grew impatient — like many — with plots that seemed to circle compulsively around the same issues week after week, played out in arguments that reduced a formidable cast of characters (and likeable actors) into tiresomely broken records. (The death of Dale [Jeffrey DeMunn] in the antepenultimate episode came as a relief, signaling that the series was fed up with its own moral center.)

Too, there is simply a feeling that more should be happening on a show about the zombie apocalypse; events should play out on a larger scale, balancing the conflicts among characters with action sequences on the level of the firebombing of Atlanta that opens “Chupacabra.” Part of the problem, I suspect, is that the ZA has been visualized so thoroughly in the decades since George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead; books like Max Brooks’s Zombie Survival Guide and World War Z, not to mention the many sequels, remakes, and ripoffs of Romero’s 1968 breakthrough, have fleshed out the undead plague on a planetary scale. The blessing of this most fecund of horror genres (second only, perhaps, to vampires) is also its curse: too much has been said, too many bottoms of barrels scraped, too many expectations raised. When the Centers for Disease Control put out preparedness warnings, it’s a safe bet the ante has been upped.

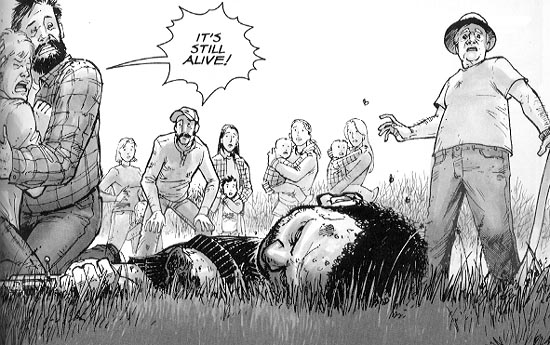

Of course, the most proximate source of raised expectations is the comic book and graphic novel series that originated The Walking Dead; Robert Kirkman, Tony Moore, and Charlie Adlard captured lightning in a bottle with their brisk yet methodical storytelling, whose black-and-white panels powerfully recall Romero’s foundational film, and whose pacing — in monthly bites of thirty pages — lends itself to a measured unfolding that has so far eluded the TV version. I’m less interested in discrepancies between the comic and the show than in the formal (indeed, ontological) problems of adaptation they illustrate: like Zack Snyder’s Watchmen movie, some fundamental, insurmountable obstruction seems to exist between the two forms of visual storytelling that otherwise seem so suited to mutual transcoding.

On a surface level, what works in the comic — the mise-en-scene of an emptied world, a uniquely American literalization of existential crisis through the metaphor of reanimated, cannibalistic corpses — works beautifully on screen. And person by person, the show brings the characters of the page to life (an artful act of reanimation itself, I suppose). But what it hasn’t done, and maybe never can do, is recreate the comic’s particular style of punctuation, doling out panels that closely attend to nuances of expression and shifts in lighting, then interleaving those orderly moments of psychological observation with big, raw shocks of splash pages that bring home the sickening spectacle of existence as eventual prey.

I’ll tune in tonight for the finale, and without question I will be there to devour season three. Furthermore, I’ll defend The Walking Dead — in both its incarnations — as some of the best horror that’s currently out there. But I’ll be watching the show out of a certain duty to the genre, whereas the comic, which I’m saving up to read in blocks of 10 and 12 issues at a go, I’ll savor as such stories are meant to be savored: late at night, alone in the quiet house, by a lamp whose glow might as well be the last light left in a world gone dark.