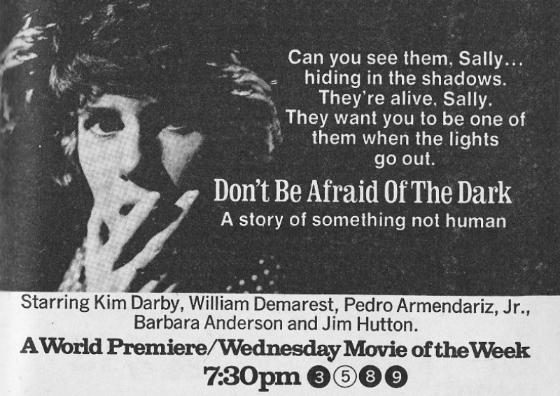

It’s hard to pinpoint the primal potency of the original Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark, the 1973 telefilm about a woman stalked by hideous little troll monsters in the shadowy old house where she lives with her husband. The story itself, a wisp of a thing, has the unexplained purity of a nightmare piped directly from a fevered mind: both circuitously mazelike and stiflingly linear, it’s like watching someone drown in a room slowly filling with water. As with contemporaries Rosemary’s Baby and The Stepford Wives, it’s a parable of domestic disempowerment built around a woman whose isolation and vulnerability grow in nastily direct proportion to her suspicion that she is being hunted by dark forces. All three movies conclude in acts of spiritual (if not quite physical) devouring and rebirth: housewives eaten by houses. To the boy I was then, Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark provoked a delicious, vertiginous sliding of identification, repulsion, and desire: the doomed protagonist, played by Kim Darby, merged the cute girl from the Star Trek episode “Miri” with the figure of my own mother, whose return to full-time work as a public-school librarian, I see now, had triggered tectonic shifts in my parents’ relationship and the continents of authority and affection on which I lived out my childhood. These half-repressed terrors came together in the beautiful, grotesque design of the telefim’s creatures: prunelike, whispery-voiced gnomes creeping behind walls and reaching from cupboards to slice with razors and switch off the lights that are their only weakness.

The 2011 remake, which has nothing of the original’s power, is nevertheless valuable as a lesson in the danger of upgrading, expanding, complicating, and detailing a text whose low-budget crudeness in fact constitutes televisual poetry. Produced by Guillermo del Toro, the movie reminds me of the dreadful watering-down that Steven Spielberg experienced when he shifted from directing to producing in the 1980s, draining the life from his own brand (and is there not a symmetry between this industrial outsourcing of artistry and the narrative’s concern with soul-sucking?). The story has been tampered with disastrously, introducing a little girl to whom the monsters (now framed as vaguely simian “tooth fairies”) are drawn; the wife, played by a bloodless Katie Holmes, still succumbs in the end to the house’s demonic sprites, but the addition of a maternal function forces us to read her demise as noble sacrifice rather than nihilistic defeat, and when husband (Guy Pearce) walks off with daughter in the closing beat, it comes unforgivably close to a happy ending. As for the monsters, now more infestation than insidiousness, they skitter and leap in weightless CGI balletics, demonstrating that, as with zombies, faster does not equal more frightening. But for all its evacuation of purpose and punch, the remake is useful in locating a certain undigestible blockage in Hollywood’s autocannibalistic churn, enshrining and immortalizing — through its very failure to reproduce it — the accidental artwork of the grainy, blunt, wholly sublime original.