In his essay “Before and After Right Now: Sequels in the Digital Era,” Nicholas Rombes gives an example of the troubling way that CGI has eroded our trust in visual reality. Citing the work of Lola Visual Effects to digitally “youthen” the lead actors in the 2006 film X-Men: The Last Stand, Rombes cites a line from the effects house’s website: “Our work has far-reaching implications from extending an actor’s career for one more sequel to overall success at the box of?ce. We allow actors and studios to create one more blockbuster sequel (with the actor’s fan base) by making the actor look as good (or better) than they did in their ?rst movie.” Rombes responds: “What is there to say about such a brash and unapologetic thing as this statement? The statement was not written by Aldous Huxley, nor was it a darkly funny dystopian story by George Saunders. This is a real, true, and sincere statement by a company that digitally alters the faces and bodies of the actors we see on the screen, a special effect so seamless, so natural that its very surrealism lies in the fact that it disguises itself as reality.”

Before we adjudicate Rombes’s claim, we might as a thought experiment try to imagine the position from which his assertion can be made – the nested conditionals that make such a response plausible in the first place. If a spectator encounters X-Men: The Last Stand without prior knowledge of any kind, including the likelihood that such a film will employ visual trickery; if he or she is unaware of the overarching careers, actual ages, and established physiognomies of Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellan; and perhaps most importantly if that viewer cannot spot digital airbrushing that even now, a scant six years later, looks like a heavy coat of pancake makeup and hair dye, then perhaps we can accept Rombes’s accusation of hubris on the part of the visual-effects house. On the other hand, how do we explain the larger incongruity in which Rombes premises his critique of the “seamless … natural” and thus presumably unnoticeable manipulation on a widely-available text, part of Lola’s self-marketing, that highlights its own accomplishment? In short, how can a digital effect be simultaneously a surreptitious lie in one register and a trumpeted achievement in another? Is this characterization not itself an example of misdirection, the impossible masquerading as the possible, a kind of rhetorical special effect?

The truth is that Rombes’s statement in all its dudgeon, from an otherwise astute observer of cinema in the age of digital technologies, suggests something of the problem faced by film and media studies in relation to contemporary special effects. We might describe it as a problem of blind spots, of failing to see what is right before our eyes. For it is both an irony and a pressing concern for theoretical analysis that special effects through their very visibility – a visibility achieved both in their immediate appearance, where they summon the powers of cleverly-wrought illusion to create convincing displays of fantasy, and in their public afterlife, where they replicate and spread through the circulatory flows of paratexts and replay culture – lull the critical gaze into selective inattention, foregrounding one set of questions while encouraging others to slip from view.

By hailing CGI and the digital mode of production it emblematizes as a decisive break with the practices that preceded it, Rombes acquiesces to the terms on which special effects have always – even in predigital times – offered themselves through From the starting point of what Sean Cubitt calls “the rhetoric of the unprecedented,” such scholarship can only unfold an analysis whose polarities, whether celebratory or condemnatory, mark but one axis of debate among the many opportunities special effects provide to reassess the changing nature of textuality, storytelling, authorship, genre, and performance in the contemporary mediascape. A far-ranging conversation, in other words, is shut down in favor of a single set of concerns, organized with suspicious tidiness around a (rather abstract) distinction between truth and falsehood. This distinction structures debates about special effects’ “spectacular” versus “invisible” qualities; their “success” or “failure” as illusions; their “indexicality” or lack of it; and their “naturalness” versus their “artificiality.” I mean to suggest not that such issues are irrelevant to the theorization of special effects, but that their ossification into a default academic discourse has created over time the impression that special effects are only about such matters as “seamless … disguise.”

Perniciously, by responding to CGI in this way, special-effects scholarship participates in the ongoing production of a larger episteme, “the digital,” along with its constitutive other, “the analog.” Although it is certainly true that the underlying technologies of special-effects design and manufacture, like those of the larger film, television, and video game industries in which such practices are embedded, have been comprehensively augmented and in many instances replaced outright by digital tools, the precise path and timing by which this occurred are nowhere near as clean or complete as the binary “analog/digital” makes them sound. In point of fact, CG effects, so often treated as proof-in-the-pudding of cinema’s digital makeover, not only borrowed their form from the practices and priorities of their analog ancestry, but preserve that past in a continued dependence on analog techniques that ride within their digital shell like chromosomal genetic structures. In a narrowly localized sense, digital effects may be the final product, but they emerge from, and feed in turn, complex mixtures of past and present technologies.

Our neglect of this hybridity and the counternarrative to digital succession it provides is fueled more than anything else by a refusal to engage with historical change – indeed, to engage with the very fact of history as a record of incremental and uneven development. Consider the way in which Rombes’s charge against CGI rehearses almost exactly the terms of Stephen Prince’s influential essay “True Lies: Perceptual Realism: Digital Images, and Film Theory.” “What is new and revolutionary about digital imaging,” Prince wrote, “is that it increases to an extraordinary degree a filmmaker’s control over the informational cues that establish perceptual realism. Unreal images have never before seemed so real.” (34) Prince’s claim about the “extraordinary” nature of digital effects was written in 1996 and refers to movies such as The Abyss (1989), Jurassic Park (1993), and Forrest Gump (1994), all of which featured CG effects alleged to be photorealistic to the point of undetectability. Rombes, writing in 2010, bases his claim about digital effects’ seduction of reality on the tricks in a film released in 1996. “What happens,” Rombes asks, “when we create a realism that outstrips the detail of reality itself, when we achieve and then go beyond a one-to-one correspondence with the real world?” (201) The answer, of course, is that one more special effect has been created from the technological capabilities and stylistic sensibilities of its time: capabilities and sensibilities that may appear transparent in the moment, but whose manufacture quickly becomes apparent as the imaging norm evolves. If digital effects are as subject to aging as any other sort of special effects, then concerns about the threat they pose to reality become empty alarms, destined to be viewed with amusement, if not ridicule, by future generations of film theorists.

The key to dissolving the impasse at which theories of digital visual effects find themselves lies in restoring to all special effects a temporality and interconnectedness to other layers of film and media culture. The first step lies in acknowledging that special effects are always undergoing change; the state of the art is a moving target. Laura Mulvey’s term for this process is the “clumsy sublime.” She refers to the use of process shots in classical Hollywood to rear-project footage behind actors – effects intended to pass unnoticed in their time, but which now leap out at us precisely in their clumsiness, their detectability.

The lesson we should take from this is not that some more lasting “breakthrough” in special effects waits around the corner, but that the very concept of the breakthrough is structured into state-of-the-art special effects as a lure for the imagination of spectators and theorists alike. The danger is not of realer-than-real digital effects, but our overconfidence in critically assessing objects that are predicated on misdirection and the promise of conquered frontiers – and our mistaken assumption that we as scholars see these processes more objectively or accurately than prior generations. In this sense, special-effects scholarship performs the very susceptibility of which it accuses contemporary audiences, accepting as fact the paradigm-shifting superiority of digital effects, rather than seeing that impression of superiority as itself a byproduct of special-effects discourse.

In this way, current scholarship imports a version of spectatorship from classical apparatus theory of the 1970s, along with a 70s-era conception of the extent and limit of the standard feature film text. Both are holdovers of an earlier period of theorizing the film text and its impact on the viewer, and are jarringly out of date when applied to contemporary media, in their cycles of replay and convergence which break texts apart and combine them in new ways, as well as to the audience, which navigates these swarming texts according to their own interests, their own “philias.” The use of obsolete models to describe special effects is all the more ironic for the appeals such models make to a transcendent “new.” The notion that the digital, as emblematized by CGI, represents a qualitative redrafting of cinema’s indexical contract with audiences, holds up only under the most restrictive possible picture of spectatorship: it imagines special effects as taking place in a singular, timeless instant of encounter with a viewer who has only two options, accepting the special effect as unmediated event or rejecting it as artifice. That special-effects theory from Andre Bazin and Christian Metz onward has allowed for bifurcated consciousness on the part of the viewer is, in the era of CGI, set aside for accounts of special effects that force them into a real/unreal binary. The digital effect and its implied spectator are trapped in a synchronic isolation from which it is impossible to imagine any other way to conceptualize the work of special effects outside the moment of their projection. Even accounts of special effects’ semiosis, like Dan North’s, that foreground their composite nature; their role in the genres of science fiction (Vivian Sobchack), the action blockbuster (Geoff King), or Aristotelian narrative (Shilo McClean), only scratch the surface of the complex objects special effects actually are.

What really changes in the clumsy sublime is not the special effect but our perception of it, an interpretation produced not through Stephen Prince’s perceptual cues, Scott Bukatman’s kinesthetic immersion in an artificial sublime, or Tom Gunning’s appeal of the attraction – though all three may indeed be factors in the first moment of seeing the effect – but by a more complex and longitudinal process involving conscious and unconscious comparisons to other, similar effects; repeated exposure to and scrutiny of special effects; behind-the-scenes breakdowns of how the effect was produced; and commentaries and reactions from fans. Within this matrix of evaluation, the visibility or invisibility, that is to say the “quality,” of special effects, is not a fixed attribute, but a blackboxed output of the viewer, the viewing situation, and the special effect’s enunciatory context in a langue of filmic manipulation.

According to the standard narrative, some special effects hide, while others are meant to be seen. Wire removal and other forms of “retouching” modify in subtle ways an image that is otherwise meant to pass as untampered recording of profilmic reality, events that actually occurred as they seem to onscreen. “Invisible” effects perform a double erasure, modifying images while keeping that modifying activity out of consciousness, like someone erasing their own footsteps with a broom as they walk through snow. So-called “visible” special effects, by contrast, are intended to be noticed as the production of exceptional technique, capitalizing on their own impossibility and our tacit knowledge that events on screen never took place in the way they appear to. The settings of future and fantasy worlds, objects, vehicles, and performers and their actions are common examples of visible special effects.

This much we have long agreed on; the distinction goes back at least as far as Metz, who in “Trucage and the Film” proposed a taxonomy of special effects broad enough to include wipes, fades, and other transitions as acts of optical trickery not ordinarily considered as such. Several things complicate the visible/invisible distinction, however. Special effects work is explored in publications and in home-video extras, dissected by fans, and employed in marketing appeals. These paratextual forces, which extend beyond the frame and the moment of viewing, tend inexorably to tip all effects work eventually into the category of “visible.” But the ongoing generation of a clumsy sublime reveals a more pervasive process at work: the passage of time, which steadily works to open a gap between a special effect’s intended and actual impact. Dating is key to dislodging reductive accounts of special effects’ operations. The clumsy sublime is a succinctly profound insight into the way that film trickery can shift over time to become visible in itself as a class of techniques to be evaluated and admired, opening up discussions about special effects beyond the binary of convincing/unconvincing that has hamstrung so many conversations about them.

If today’s digital special effects can age and become obsolete – and there is no reason to think they cannot – then this undermines the idea that there is some objective measure of their quality; “better” and “worse” become purely relational terms. It also raises the prospect that the digital itself is more an idea than an actual practice: a perception we hold – or a fantasy we share – about the capabilities of cinema and related entertainments. The old distinction that held during the analog era, between practical and optical effects, constituted a kind of digital avant la lettre; practical effects, performed live before the camera, were considered “real,” while optical effects, created in post-production, were “virtual.” The coming of CGI has remapped those categories, making binaries into bedfellows by collapsing practical and optical into one primitive catchall, the “analog,” defined against its contemporary other, the “digital.” Amid such lexical slippages and epistemic revisions, current scholarship is insufficiently reflexive about apprehending the special effect. We have been too quick to get caught up in and restate the terms – Philip Rosen calls it “the rhetoric of the forecast” – by which special effects discursively promote themselves. In studying illusion, we risk contributing to another, larger set of illusions about cinematic essence.

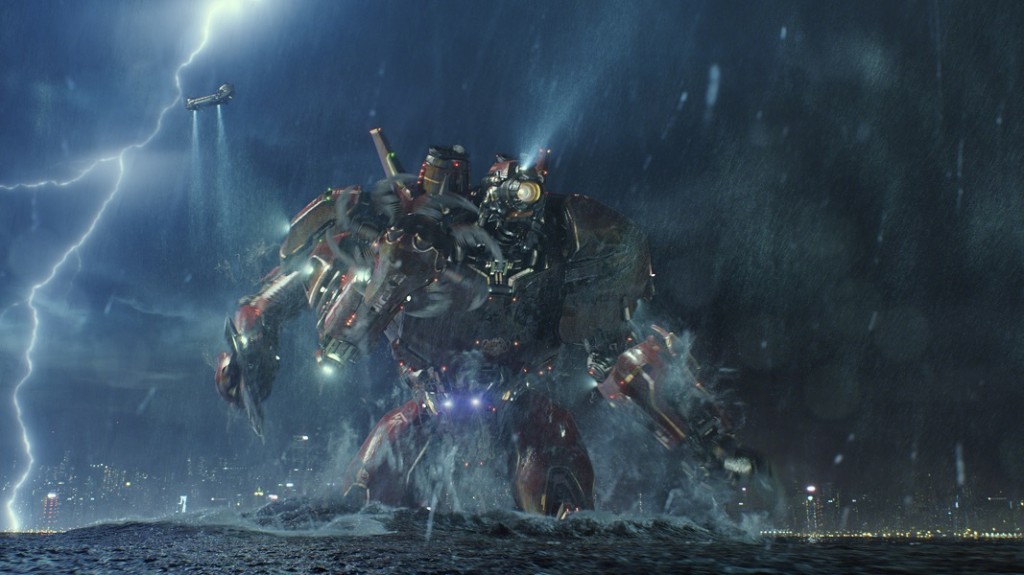

What is revealed, then, by stepping out of our blind spot to survey special effects across the full range of their operations and lifespans? First, we see that special effects are profoundly composite in nature, marrying together elements from different times and spaces. But the full implications of this have not been examined. Individual frames are indeed composites of many separate elements, but viewed diachronically, special effects are also composited into the flow of the film – live-action intercut with special effects shots as well as special effects embedded within the frame. This dilutes our ability to quarantine special effects to particular moments; we can speak of “special-effects films” or “special-effects sequences,” but what percentage of the film or sequence consists of special effects, and in what combination? Consider how such concerns shape our labeling of a given movie as a “digital effects” film. Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) and The Matrix (1999) each contained only a few minutes of shots in which CG elements played a part, while the rest of their special effects were produced by old-school techniques such as animatronics and prosthetics. Yet we do not call these movies “animatronics films” or “prosthetics films.” The sliding of the signified of the film under the signifier of the digital suggests that, when it comes to special effects, we follow a technicist variation of the “one-drop rule,” where the slightest collusion of computers is an excuse to treat the whole film a digital artifact.

What, then, is the actual “other” to indexicality posed by special effects, digital and analog alike? It is insufficient simply to label it the “nonindexical”; in slapping this equivalent of “here there be dragons” on the terra incognita at the edge of our map’s knowability, we have not answered the question but avoided it. The truth is that all special effects, even digital ones, are indexical to something; they can all, in a certain sense, be “sourced” to the real world and real historical moments. If nothing else, they are records of moments in the evolution of imaging, and because this evolution is driven not only by technology but by style, it is always changing without destination. (As Roland Barthes observes, the fashion system has no end.) Digital special effects record the expressions of historically specific configurations of software and hardware just as, in the past, analog special effects recorded physical arrangements of miniatures and paintings on glass. Nowadays, with all analog effects retroactively rendered “real” by the digital, even processes such as optical printing and traveling mattes have come to bear their own indexical authenticity, just as film grain and lens flares record specifics of optics and celluloid stock. But the indexical stamp of special effects goes deeper than their manufacture. Visible within them are design histories and influences, congealed into the object of the special effect and frozen there, but available for unpacking, comparison, fetishization, and emulation by audiences increasingly organized around the collective intelligence of fandom. Furthermore, because of the unique nature of special effects (that is, as “special” processes celebrated in themselves), materials can frequently be found which document the effect’s manufacture, and in many cases – preproduction art, maquettes, diagrams – themselves represent evolutionary stages of the special effect.

Every movie, by virtue of residing inside a rationalized industrial system, sits atop a monument of planning and paperwork. In films that are heavy on design and special effects, this paperwork takes on archival significance, becoming technical archeologies of manufacture. Our understanding of what a special effect is must begin by including these stages as part of its history – the creative and technological paths from which it emerged. We recognize that what we see on screen is only a surface trace of much larger underlying processes: the very phenomenon of making-of supposes there is always more to the (industrial) story.

Following this logic, we see that special effects, even digital ones, do not consist of merely the finished, final output on film, but a messy archive of materials: the separate elements used to film them and the design history recorded in documents such as concept art and animatics. Special effects leave paratextual trails like comets. It is only because of these trails that behind-the-scenes materials exist at all; it is what we look at when we go behind the scenes. Furthermore, we see that special effects, once “finished,” themselves become links in chains of textual and paratextual influence. It is not just that shots and scenes provide inspiration for can-you-top-this performances of newer effects, but that, in the amateur filmmaking environments of YouTube and “basementwood,” effects are copied, emulated, downgraded, upgraded, spun, and parodied – each action carrying the effect to a new location while rendering it, through replication, more pervasive in the mediascape. Special effects, like genre, cannot be copyrighted; they represent a domain of audiovisual replication that follows its own rules, both fast-moving and possessed of the film nerd/connoisseur’s long-tail memory. Special effects originate iconographies in which auras of authorship, collections of technical fact, artistic influences, teleologies of progress/obsolescence, franchise branding, and hyperdiegetic content coexist with the ostensible narrative in which the special effect is immediately framed. These additional histories blossom outward from our most celebrated and remembered special effects; in fact, it is the celebration and remembering that keeps the histories alive and developing.

All of this contributes to what Barbara Klinger has called the “textual diachronics” of a film’s afterlife: an afterlife which, given its proportional edge over the brief run of film exhibition, can more frankly be said to constitute its life. Special effects thus mark not the erasure of indexicality but a gold mine of knowledge for those who would study media evolution. Special effects carry information and behave in ways that go well beyond their enframement within individual stories, film properties, or even franchises. Special effects are remarkably complex objects in themselves: their engineering, their semiotic freight, their cultural appropriation, their media “travel,” their hyperdiegetic contribution.

What seems odd is that while one branch of media studies is shifting inexorably toward models of complexity and diffusion, travel and convergence, multiplicity and contradiction, the study of special effects still grapples with its objects as ingredients of an older conception of film: the two-hour self-contained text. What additional and unsuspected functions lurk in the “excess” so commonly attributed to prolonged displays of special effects? Within the domains of franchise, transmedia storytelling, and intertextuality, the fragmentation of texts and their subsequent recontainment within large-scale franchise operations makes it all the more imperative to find patterns of cluster and travel in the new mediascape, along with newly precise understandings of the individuals/audiences who drive the flow and give it meaning.

To say that CG effects have become coextensive with filmmaking is not to dismiss contemporary film as digital simulacrum but to embrace both “digital effects” and “film” as intricate, multilayered, describable, theorizable processes. To insist on the big-screened, passively immersed experience of special effects as their defining mode of reception is to ignore all the ways in which small screens, replays, and paratextual encounters open out this aspect of film culture, both as diegetic and technological engagement. To insist that special effects are mere denizens of the finished film frame is to ignore all the other phases in which they exist. And to associate them only with the optical regime of the cinematic apparatus (expressed through the hypnotic undecidable of real/false, analog/digital) is to ignore the ways in which they spread to and among other media.

The argument I have outlined in this essay suggests a more comprehensive way of conceptualizing special effects in the digital era, seeing them not just as enhancements of a mystificatory apparatus but as active agents in a busy, brightly-lit, fully conscious mediascape. In this positivist approach, digital effects contribute to the stabilizing and growth of massive fantastic-media franchises and the generation of new texts (indeed, of the concept of “new” itself). In all of these respects, digital special effects go beyond the moment of the screen that has been their primary focus of study, to become something more than meets the eye.