I look at Blade Runner as the last analog science-fiction movie made, because we didn’t have all the advantages that people have now. And I’m glad we didn’t, because there’s nothing artificial about it. There’s no computer-generated images in the film.

— David L. Snyder, Art Director

Any movie that gets a “Five-Disc Ultimate Collectors Edition” deserves serious attention, even in the midst of a busy semester, and there are few films more integral to the genre of science fiction or the craft of visual effects than Blade Runner. (Ordinarily I’d follow the stylistic rules about which I browbeat my Intro to Film students and follow this title with the year of release, 1982. But one of the many confounding and wonderful things about Blade Runner is the way in which it resists confinement to any one historical moment. By this I refer not only to its carefully designed and brilliantly realized vision of Los Angeles in 2019 [now a mere 11 years away!] but the many-versioned indeterminacy of its status as an industrial artifact, one that has been revamped, recut, and released many times throughout the two and a half decades of its cultural existence. Blade Runner in its revisions has almost dissolved the boundaries separating preproduction, production, and postproduction — the three stages of the traditional cinematic lifecycle — to become that rarest of filmic objects, the always-being-made. The only thing, in fact, that keeps Blade Runner from sliding into the same sad abyss as the first Star Wars [an object so scribbled-over with tweaks and touch-ups that it has almost unraveled the alchemy by which it initially transmuted an archive of tin-plated pop-culture precursors into a golden original] is the auteur-god at the center of its cosmology of texts: unlike George Lucas, Ridley Scott seems willing to use words like “final” and “definitive” — charged terms in their implicit contract to stop futzing around with a collectively cherished memory.)

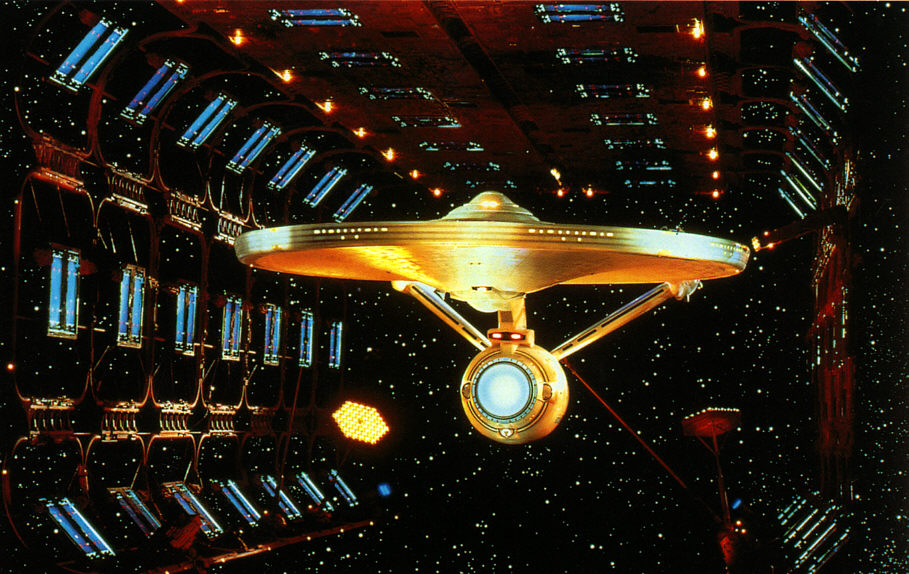

I grabbed the DVDs from Swarthmore’s library last week to prep a guest lecture for a seminar a friend of mine is teaching in the English Department, and in the course of plowing through the three-and-a-half-hour production documentary “Dangerous Days” came across the quote from David L. Snyder that opens this post. What a remarkable statement — all the more amazing for how quickly and easily it goes by. If there is a conceptual digestive system for ideas as they circulate through time and our ideological networks, surely this is evidence of a successfully broken-down and assimilated “truth,” one which we’ve masticated and incorporated into our perception of film without ever realizing what an odd mouthful it makes. There’s nothing artificial about it, says David Snyder. Is he referring to the live-action performances of Harrison Ford, Rutger Hauer, and Sean Young? The “retrofitted” backlot of LA 2019, packed with costumed extras and drenched in practical environmental effects from smoke machines and water sprinklers? The cars futurized according to the extrapolative artwork of Syd Mead?

No: Snyder is talking about visual effects — the virtuoso work of a small army headed by Douglas Trumbull and Richard Yuricich — a suite of shots peppered throughout the film that map the hellish, vertiginous altitudes above the drippy neon streets of Lawrence G. Paull’s production design. Snyder refers, in other words, to shots produced exclusively through falsification: miniature vehicles, kitbashed cityscapes, and painted mattes, each piece captured in multiple “passes” and composited into frames that present themselves to the eye as unified gestalts but are in fact flattened collages, mosaics of elements captured in radically different scales, spaces, and times but made to coexist through the layerings of the optical printer: an elaborate decoupage deceptively passing itself off as immediate, indexical reality.

I get what Snyder is saying. There is something natural and real about the visual effects in Blade Runner; watching them, you feel the weight and substance of the models and lighting rigs, can almost smell the smoky haze being pumped around the light sources to create those gorgeous haloes, a signature of Trumbull’s FX work matched only by his extravagant ballet of ice-cream-cone UFOs amid boiling cloudscapes and miniature mountains in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. But what no one points out is that all of these visual effects — predigital visual effects — were once considered artificial. We used to think of them as tricks, hoodwinks, illusions. Only now that the digital revolution has come and gone, turning everything into weightless, effortless CG, do we retroactively assign the fakery of the past a glorious authenticity.

Or so the story goes. As I suggest above, and have argued elsewhere, the difference between “artificial” and “actual” in filmmaking is as much a matter of ideology as industrial method; perceptions of the medium are slippery and always open to contestation. Special and visual effects have always functioned as a kind of reality pump, investing the “nonspecial” scenes and sequences around them with an air of indexical reliability which is, itself, perhaps the most profound “effect.” With vanishingly few exceptions, actors speak lines written for them; stories are stitched into seamless continuity from fragments of film shot out of order; and, inescapably, a camera is there to record what’s happening, yet never reveals its own existence. Cinema is, prior to everything else, an artifact, and special effects function discursively to misdirect our attention onto more obvious classes of manipulation.

Now the computer has arrived as the new trick in town, enabling us to rebrand everything that came before as “real.” It’s an understandable turn of mind, but one that scholars and critics ought to navigate carefully. (Case in point: Snyder speaks as though computers didn’t exist at the time of Blade Runner. Yet it is only through the airtight registration made possible by motion-control cinematography, dependent on microprocessors for precision and memory storage for repeatability, that the film’s beautiful miniatures blend so smoothly with their surroundings.) It is possible, and worthwhile, to immerse ourselves in the virtual facade of ideology’s trompe-l’oeil — a higher order of special effect — while occasionally stepping back to acknowledge the brush strokes, the slightly imperfect matte lines that seam the composited elements of our thought.