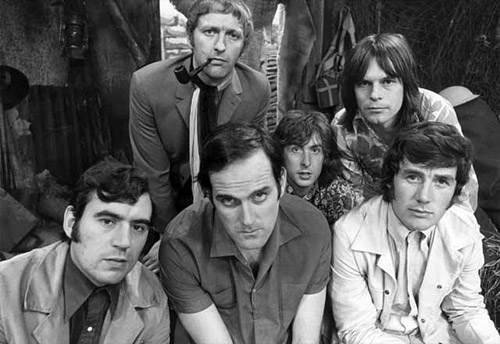

Ordinarily I’d start my post with a by-now-boilerplate apology for lagging behind the news, but in this case I will leave aside the ritual lament (“I’m just so busy this semester!”) and instead make proud boast of my lateness, boldly owning up to the fact that, although it was forty years ago last week that Monty Python’s Flying Circus had its first broadcast, I’m just getting around to remarking on it today. Seems only (il)logical to do so, given that one of Python‘s most fundamental and lasting alterations to the cultural landscape in which I grew up was to validate the non sequitur as an acceptable conversational — and often behavioral — gambit.

Let me explain. For me and my friends in grade school, the early-to-mid-seventies were a logarithmically-increasing series of social revelations, sometimes depressingly gradual, other times bruisingly abrupt, that we were “weird.” Our weirdness went by several aliases. The labels bestowed by forgiving parents and teachers were things like “smart,” “bright,” “eccentric,” “unusual,” and “creative.” Whereas the ones that arrived not from above but laterally, hurled like snowballs in the schoolyard or graffitied in ball-point across our notebooks, were more brutally and colorfully direct, and thus of course more convincing: “freak,” “spaz,” and — for me in particular, since it vaguely rhymes with Rehak — “retard.”

I see now that almost all of these phrases had their grain of truth, their icy core, their scored ink-line. In our weirdness we were smart and unusual and creative; we were also undeniably freakish, and as our emotional gyroscopes whirled wildly in search of some stable configuration, we were, by turns, spastically overenthusiastic and retardedly slow to adapt. We were book and comic readers, TV watchers, play actors, cartoon artists, model builders, rock collectors. We were boys. We liked science fiction and fantasy. Our skills and deficits were misdistributed and extreme: vastly vocabularied but garbled by braces and retainers; carefully observant but blindered by thick glasses; handsome heroes in our hearts, chubby or skinny buffoons in person. Many of us were good at science and math, others at art and theater. None of us did particularly well on the athletic field, though we did provide workouts for the kids who chased us.

Me, I made model kits of monsters like the Mummy, the Wolfman, and the Creature from the Black Lagoon — all supplied by the great company Aurora, with the last mile from hobby store to home facilitated by my indulgent parents — painted them in garish and inappropriate colors, situated them behind cardboard drum kits and guitars on yarn neckstraps, and pretended they were a rock supergroup while blasting the Monkees and the Archies from my record player. (I am not making this up.)

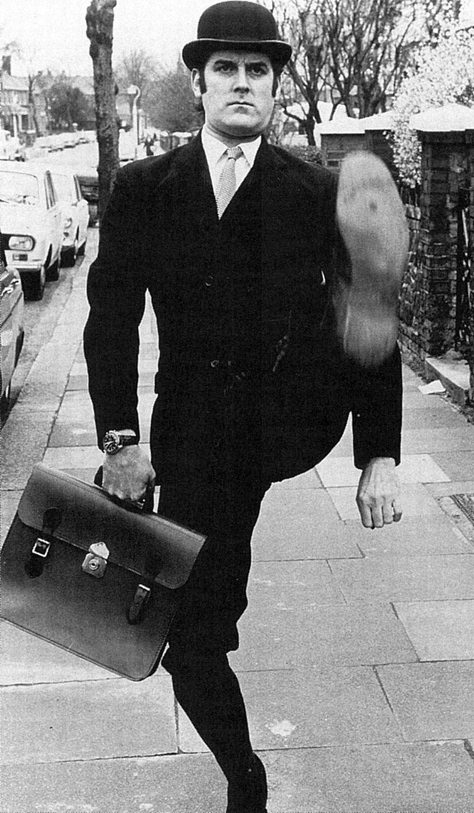

I was also a media addict, even back then, and when Monty Python episodes began airing over our local PBS station, I was instantly and utterly devoted to it. Which is not to say I liked everything I saw — a nascent fan, I quickly began drawing distinctions between the unquestionably great, the merely good, the tolerably adequate, and the terminally lame paroles that constituted the show’s langue, learning connections between these variations in quality and the industrial microepochs that gave rise to them: early, middle, and late Python. I had my favorite bits (Terry Gilliam’s animations, anything ever done or said by John Cleese) and my “mehs” (Terry Gilliam’s acting and the episode devoted to hot-air ballooning). Although or because I was stranded somewhere in the long latency separating my phallic and genital stages, I found every mention of sex and every glimpse of boob a fascinating magma of hypothetical desire and unearned shame. And, of course, it was all hysterically, tear-squirting, stomach-cramp-inducing funny.

The downside of Monty Python‘s funniness was the same as its upside: it gave all of us weirdos a shared social circuit. The show’s peculiar and specific argot of slapstick and trangression, dada and doo-doo, spread overnight to recess and classroom, connecting by a kind of dedicated party line any schlub who could memorize and repeat lines and skits from the show. In short, Monty Python colonized us, or more accurately it lit up like a discursive barium trace the preexisting nerd colony that theretofore had hidden underground in a nervous relay of quick glances, buried smiles, and raised eyebrows. Suddenly outed by a humor system from across the sea, we pint-sized Python fans stood revealed as a brotherhood of nudge-nudge-wink-wink, a schoolyard samizdat.

A good thing, but also a bad thing. The New York Times gets it exactly wrong when describing the “couple of guys in your dorm (usually physics majors, for some reason, and otherwise not known for their wit) who could recite every sketch”; according to Ben Brantley, “They could be pretty funny, those guys, especially if you hadn’t seen the real thing.” Nope — people who recite every Monty Python sketch are by definition not funny, or rather are funny only within an extremely bounded circle of folks who (A) already know the jokes and (B) accept said recitation as legal tender in their subcultural social capital. In my experience, there was no surer date-killer, no quicker way to get people to edge away from you at parties than by launching into such bonafide gems of genius as the Cheese Shoppe or the Argument Clinic. Yet we went on tagging each other as geek untouchables, comedy as contagion, as helpless before Pythonism’s viral spread as we would be, a few years on, by the replicating errata of Middle Earth and the United Federation of Planets.

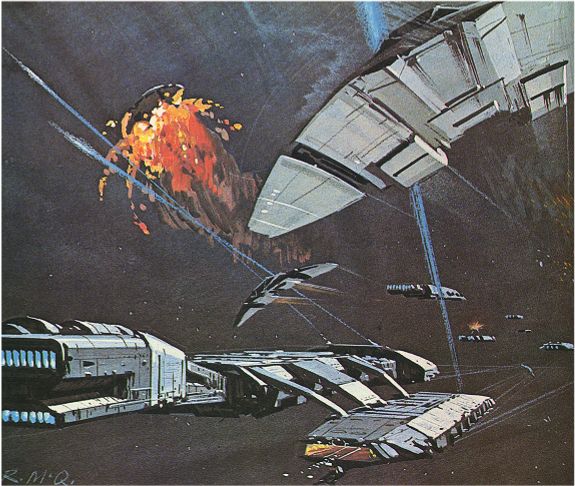

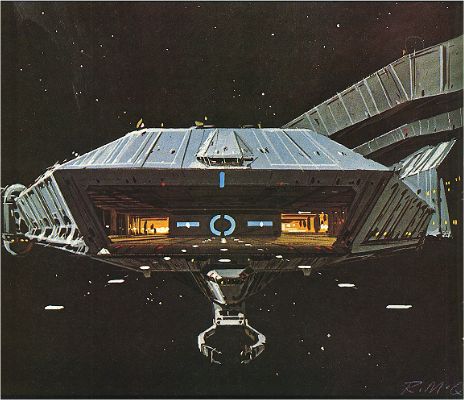

Monty Python was merely the first infusion of obsessive-compulsive nerd scholarship into which I and my friends were forced by a series of cultural imports from Britain: grand stuff like The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Alan Moore, and the computer game Elite. The three movies I like to name as my favorites of all time each have substantial UK components: Star Wars (1977) was filmed partly at Elstree Studios, Superman (1978) at Pinewood and Shepperton Studios, and Alien (1979), with Ridley Scott at the helm, at Shepperton and Bray Studios. And the trend continues right to present day: my favorite band is Genesis, I can’t get enough of Robbie Coltrane’s Cracker, and the science-fiction masterpiece of the summer was not District 9 (which gets high marks nevertheless) but the superb Children of Earth.

I sometimes wonder what to call this collection of British art and entertainment, this odd cultural constellation that seems to obey no organizing principle except its origins in England and its relevance to my development. How do you draw a boundary around a miscellany of so much that is good and essential about imaginary lives and their real social extrusions? Maybe I’m seeking a word like supergenre or metagenre, but those seem too big; try idiogenre, some way of systematizing a group of texts whose common element is their locus in a particular, historically-shaped subjectivity (my own) that is simultaneously a shared condition. The comic tragedy of the nerd, a figure both stranded on the social periphery yet crowded by his peers, lonely yet overfriended, renegade frontiersman and communal sheep, a silly-walking man with an entire Ministry of Silly Walks looming behind him.

I blame, and thank, England.