Ooooh, the next two weeks have me tingling with anticipation: it’s time again for the Democratic National Convention and its bearded-Spock alternate-universe doppelganger, the Republican National Convention. I intend to watch from my cushy couch throne, which magisterially oversees a widescreen high-def window into the mass ornament of our country’s competing electoral carnivals.

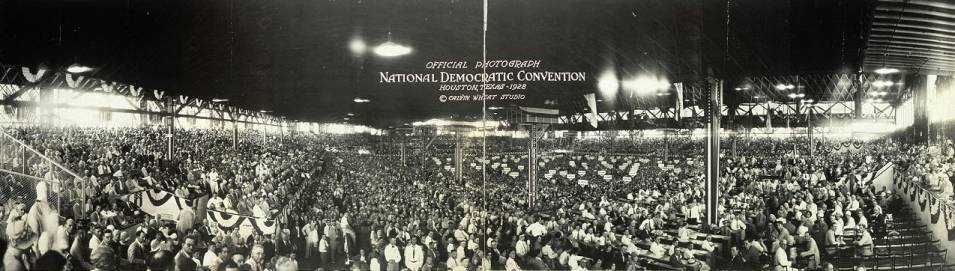

Strangely, the Olympics didn’t hold me at all (beyond the short-lived controversy of their shameless simulationism), even though they served up night after night of HD spectacle. It wasn’t until I drove into the city last week to take in a Phillies game that I realized how hungry I am to immerse myself in that weird, disembodied space of the arena, where folks to the right and left of you are real enough, but rapidly fall away into a brightly-colored pointillist ocean, a rasterized mosaic that is, simply, the crowd, banked in rows that rise to the skyline, a bowl of enthusiastic spectatorial specks training their collective gaze on each other as well as inward on a central proscenium of action. At the baseball game I was in a state of happy distraction, dividing my attention among the actual business of balls, strikes, and runs; the fireworky HUDs of jumbotrons, scoreboards, and advertising banners, some of which were static billboards and others smartly marching graphics; the giant kielbasa (or “Bull Dog”) smothered with horseradish and barbecue sauce clutched in my left hand, while in my right rested a cold bottle of beer; and people, people everywhere, filling the horizon. I leaned over to my wife and said, “This is better than HD — but just barely.”

Our warring political parties’ conventions are another matter. I don’t want to be anywhere near Denver or Minneapolis/St. Paul in any physical, embodied sense. I just want to be there as a set of eyes and ears, embedded amid the speechmakers and flagwavers through orbital crosscurrents of satellite-bounced and fiber-optics-delivered information flow. I’ll watch every second, and what I don’t watch I’ll DVR, and what I don’t DVR I’ll collect later through the discursive lint filters of commentary on NPR, CNN, MSNBC, and of course Comedy Central.

The main pleasure in my virtual presence, though, will be jumping around from place to place inside the convention centers. I remember when this joyous phenomenon first hit me. It was in 1996, when Bill Clinton was running against Bob Dole, and my TV/remote setup were several iterations of Moore’s Law more primitive than what I wield now. Still, I had the major network feeds and public broadcasting, and as I flicked among CBS, NBC, ABC, and PBS (while the radio piped All Things Considered into the background), I experienced, for the first time, teleportation. Depending on which camera I was looking through, which microphone I was listening through, my virtual position jumped from point to point, now rubbing shoulders with the audience, now up on stage with the speaker, now at the back of the hall with some talking head blocking my view of the space far in the distance where I’d been an instant previously. It was not the same as Classical Hollywood bouncing me around inside a space through careful continuity editing; nor was it like sitting in front of a bank of monitors, like a mall security guard or the Architect in The Matrix Reloaded. No, this was multilocation, teletravel, a technological hopscotch in increments of a dozen, a hundred feet. I can’t wait to find out what all this will be like in the media environment of 2008.

As for the politics of it all, I’m sure I’ll be moved around just as readily by the flow of rhetoric and analysis, working an entirely different (though no less deterministic) register of ideological positioning. Film theory teaches us that perceptual pleasure, so closely allied with perceptual power, starts with the optical and aural — in a word, the graphic — and proceeds downward and outward from there, iceberg-like, into the deepest layers of self-recognition and subjectivity. I’ll work through all of that eventually — at least by November 4! In the meantime, though, the TV is warming up. And the kielbasa’s going on the grill.