Adapting Watchmen After 9/11

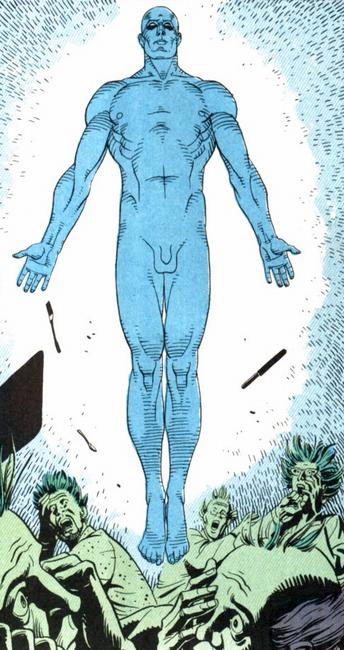

For a work that gives off such a potent impression of originality and singularity, Watchmen has always been haunted by the concept of the near-parallel, the skewed copy, the version. Start with its setting, an alternate-reality 1985. Cocked at a knowing and sardonic angle to our own, the world of Watchmen is one in which superheroes and costumed crimefighters are real, American won the Vietnam War, and Richard Nixon has just been elected to his fifth term as U.S. President. Consider too the book’s industrial origins in the early 1980s, when DC purchased a set of characters from the defunct Charlton Comics and handed them to a rising star, the British writer Alan Moore, to spin into a new series. When it became clear that the “close-ended scenario” Moore envisioned would preempt the Charlton lineup’s commercial possibilities, Moore and his collaborator, illustrator Dave Gibbons, simply reinvented them: Blue Beetle became Nite Owl, Captain Atom became Dr. Manhattan, The Question became Rorschach, and so on — an act of “reimagining” avant la lettre (1). The result, a 12-issue limited series published in 1986-1987 and collected in a single volume many times thereafter, is one of the undisputed keyworks in any canon of comic-book literature (or, if you prefer, graphic novels), winning a 1988 Hugo Award and named by Time Magazine one of the 100 best English-language novels from 1923 to 2005 (2).

But if Watchmen‘s transit across the hierarchies of culture constitutes yet another level of indeterminacy — a kind of quantum tunneling among the domains of geek, popular, and elite taste — this trajectory seemed to hit its limit at the ontological divide between the printed page and moving-image media. The drive to turn Watchmen into a movie arose early and failed often over the next two decades. Producer Joel Silver and directors Terry Gilliam and Darren Aronofsky were among those who ultimately fell before the challenge of what Moore described as an “unfilmable” text for its dependence on the formal aesthetics of comic-book storytelling (3). By the time Zack Snyder’s adaptation finally made it to the screen in 2009, the mission had grown beyond a mere cinematic “take” on the material into the production of something like a simulacrum, marshalling a host of artistic and technological resources to recreate in exact detail the panels, dialogue, and world-design of the original.

Only one thing was changed: the ending.

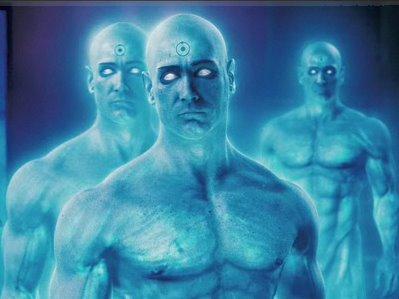

Watchmen‘s climax involves a conspiracy by the polymathic industrialist Adrian Veidt — alter-ego of the superhero Ozymandias — to correct the course of a world on the brink of nuclear armageddon. As written by Moore and drawn by Gibbons, Veidt teleports a giant, genetically-engineered squid into the heart of New York City, killing millions, and tricking global superpowers into uniting against a perceived alien invasion. Snyder’s version omits the squid in favor of a different hoax: in the movie, Dr. Manhattan, a superbeing created by atomic accident, is set up as the fall guy for a series of explosions in major world cities. As explained by Snyder and screenwriter Alex Tse in commentaries and interviews, the substitution elegantly solves a number of storytelling tangles, cutting a Gordian knot much like the one faced by Veidt. It simplifies the narrative by eliminating a running subplot; it employs a major character, Dr. Manhattan, whose godlike powers and alienation from humanity provide a logical basis for the blame he receives; perhaps most importantly, it trades an outrageous and even laughable version of apocalypse for something more familiar and believable.

Measured against the relentless fidelity of the rest of the project, the reimagined ending of Watchmen has much to say about the process of adaptation in an era of blockbuster filmmaking and ubiquitous visual effects, as well as the discursive means by which differences between one version and another are negotiated in an insistently expansive culture of seriality and transmedia. But it is also a striking and symptomatic response to an intervening real-world event, the terrorist attacks of 9/11, and our modes of visualizing apocalypse and its aftermath.

From the start, Watchmen‘s reputation for unadaptability stemmed not just from its origin as a graphic novel but from the self-reflexive way it drew on the unique phenomenology and affordances of comic-book storytelling. Its 384 pages interpolate metafictional excerpts from personal memoirs and tabloid interviews, business memos, and product brochures. The wealth of invented and implied information in these prepackaged paratexts extends the effects of Gibbons’s artwork, laid out in precise, nine-panel grids brimming with background details, from the logo of the Gunga Diner restaurant chain to the smokeless cigarettes, electric cars, and dirigible airships that signal an alternative technological infrastructure. Shaped by symmetries large and small, the comic’s plot — a mystery about the murder of costumed heroes — emerges as a jigsaw of such quotidian pieces, assembled by readers free to pause and scan back through the pages, rereading and recontextualizing, in a singularly forensic and nonlinear experience of the text.

Nowadays, the difficulty of appreciating the unprecedented nature of Watchmen is, ironically, proof of its genre-altering influence: grim dystopias and grittily “realistic” reinventions of superheroes quickly became a trend in comics as well as film, making Watchmen a distant parent of everything from Kick-Ass (Mark Millar and John Romita, Jr., 2008-2010) to Heroes (2006-2010) and The Dark Knight (Christopher Nolan, 2008). It may also be hard, in retrospect, to grasp why a detailed fictional world should pose a challenge to filmmakers. For his 1998 “special editions,” George Lucas added layers of CG errata to the backgrounds of his original Star Wars trilogy, and contemporary techniques of match-moving and digital compositing make it possible to jam every frame with fine detail. (Given that this layered ornamentation is best appreciated through freeze-frames and replays — cinematic equivalents of flipping back and forth through the pages — one might trace this aesthetic back to Watchmen as well.) Simply put, the digital transformation of filmmaking, a shift most visible in the realm of special effects but operative at every level and stage of production, has made the mounting of projects like Watchmen relatively straightforward, at least in technical terms.

But the state of the art did not emerge overnight, and Watchmen‘s path to adaptation was a slow and awkward one. Two concerns dominated early efforts to convert Moore’s and Gibbons’s scenario into a workable screenplay: compression of the comic’s scope (with a consequent reduction of its intricacy); and how to handle its setting. The economics of the blockbuster, built on the exigencies of Classical Hollywood, dictate that confusion on the audience’s part must be carefully choreographed — they should be intrigued and mystified, but not to the point where they choose to take their entertainment dollars elsewhere. Turning Watchmen into a successful feature film meant committing, or not, to a premise that probably seemed more formidable at a time when alternate realities (again, “versions”) were a limited subset of science fiction.

Sam Hamm, the first screenwriter to tackle the adaptation, rejected the squid subplot as an implausible lever for world peace, saying, “While I thought the tenor of the metaphor was right, I couldn’t go for the vehicle.” (4) His 1989 script climaxes with Veidt opening a portal in time in order to assassinate Jon Osterman before he can become Dr. Manhattan — undoing the superhuman’s deforming effects on the world. Although Veidt fails, Manhattan grasps the logic of his plan, and opts to erase himself from the timeline. The ensuing paradox unravels the alternate reality and plunges surviving heroes Nite Owl, Rorschach, and the Silk Spectre into “our” unaffected world.

It is tempting to view Hamm’s ending as a blend of science-fiction film motifs dominant at the end of the 1980s, fusing the time-traveling assassin of The Terminator (James Cameron, 1984) with the branching realities of Back to the Future 2 (Robert Zemeckis, 1989). Certainly David Hayter’s 2003 script takes the ending in a different direction: here Veidt bombards New York City with concentrated solar radiation, killing one million, in order to establish himself as a kind of benevolent dictator. Again, Veidt dies, but — in a denouement closer to the original’s — the hoax is allowed to stand, since to reveal the truth would return the world to the brink of war.

The version that Snyder finally filmed, based on a script co-authored with Alex Tse, makes just one final adjustment to the ending, one that could be seen as a synthesis of the versions that had come before: instead of solar radiation, it is Dr. Manhattan’s energy signature that destroys cities around the world, and Dr. Manhattan who takes the blame, exiling himself to explore other forms of reality.

It may be overestimating the depth of Hollywood’s imagination to suggest that its pairing of Zack Snyder and Watchmen was an inspired rather than merely functional decision — that Warner Brothers saw Snyder not just as a director with the right specializations to make their film, but as a kind of auteur of adaptation. Certainly Snyder had proved himself comfortable with vivid, subculturally cherished texts, as well as effects-intensive film production, with his first two movies, Dawn of the Dead (2004) and 300(2006). The latter film in particular, shot on a digital backlot of greenscreens with minimal sets, must have seemed an ideal resume for Watchmen, demonstrating Snyder’s ability to bring static artwork — in this case, Frank Miller’s and Lynn Varley’s — to strange, half-animated life on screen while maintaining his own distinct layer of stylization. (Snyder’s predilection for speed ramping, in which action shifts temporal gears midshot, may be his most obvious and mockable tic, but it is a clever way to substitute a cinematic signifier for comic art’s speed-line symbolalia.)

Rejecting prior half-measures at sanding off the story’s rough edges, Snyder embraced Moore’s and Gibbons’s work almost literally as a bible, letting the collected Watchmen guide production design “like an illuminated text, like it was written 2000 years ago.” (5) The prominence of this sentiment and others like it in the host of materials accompanying Watchmen‘s marketing can be seen as a discursive strategy as much as anything else, a move to reassure prospective audiences — a group clearly identified early on as a small but important base worthy of wooing, in much the manner that New Line Cinemas cultivated and calibrated its relationships with fans during the making of The Lord of the Rings. (6) Enacted at the layer of the manufactured paratextual penumbra that, as Jonathan Gray reminds us, is now de rigeur for blockbuster film events, public performances of allegiance to a single, accepted reference constitute a crucial discursive technology of adaptation, working in concert with the production technologies involved in translating fan-cherished works (7)

One such production technology doubling as discursive tool was the participation of Dave Gibbons. In DVD and Blu-Ray extras, Gibbons tours the set, posing with Snyder, all smiles, confirming the authenticity and integrity of the production. “I’m overwhelmed by the depth and detail of what I’m seeing,” he wrote of his visit. “I’m overwhelmed by the commitment, the passion, the palpable desire to do this right.” (8) Working with Moore in the 80s, Gibbons’s part in the origination of Watchmen was profound, extending far beyond the simple illustration of a script; the two brainstormed together extensively, and the story’s more reflexive and medium-aware qualities demanded near-microscopic coordination of story and image. Further, Moore’s choice to remove himself from the chain of mandatory citation that constitutes authorship as legal status, relinquishing any claim on the filmic realization of Watchmen, leaves only Gibbons to take credit for the work.

But it is hard to escape a suspicion that promotional discourses around the film lay a surreptitious finger on the scale, biasing the source’s creative center of gravity toward Gibbons, whose contributions are, after all, those most “available” to film production: the design of sets, costumes, props; character physiques and hair styles; background environments and architecture; even the framing of key shots and events. Graphic illustration and cinematic manufacture meet at the layer of the look, understood here not through film theory’s account of the gaze but the more pragmatic (drawable, buildable) framework of mise-en-scene.

Within this odd binary — the highlighting of Gibbons, the structuring absence of Moore — Snyder appears as something of a third term, positioned not as creator but as faithful cinematic translator. His mode of “authorship” is defined chiefly, and perhaps paradoxically, as a fierce and unremitting loyalty to the work of others.

All of these forces come together in the paratextual backstory of the film’s single biggest change. The tie-in publication Watchmen: The Art of the Film reprints storyboards created by Gibbons for the new ending. According to Peter Aperlo, “these new ‘pages’ were drawn at Zack Snyder’s request during pre-production, to ensure that the film’s re-imagined ending nevertheless drew from an authentic source.” (9) Completing the cycle, Gibbons also provided promotional artwork illustrating key images from the film for use in marketing. These interstitial storyboards perform a kind of suture at the industrial level of film-as-artifact and the communicational level of film-as-public-presence, knitting together the visualizations of Gibbons and Snyder in a fusion that guarantees the film’s pedigree while plastering over the hole left by Moore’s departure.

The versionness that has always haunted Watchmen is also present in our hesitation before the question of whether it is a closed, finite text or a sprawling serial object. Is there one Watchmen or many? This indeterminacy too seems embedded in the text’s fortunes from the start: whether you label it a “comic book” or “graphic novel” depends on whether you think of the original as a sequence of twelve discrete issues released one month apart, or as a single work collected between the covers of a book. Kin to Roland Barthes’s distinction between writerly and readerly texts, the latter perspective underpins perceptions of the story as something inviolate, to be protected from tampering; the former leans toward modification, experimentation, openness.

Similarly, Watchmen‘s storyworld — the intricately conceived and exhaustively detailed settings whose minutia, repeated from panel to panel, form a stressed palimpsest — displays characteristics of both a one-off extrapolation, complete unto itself, and the endlessly expandable backdrops of serial fictions like Star Trek, larger than any one instance of the text can contain.

Matt Hills uses the term hyperdiegesis to identify these “vast and detailed narrative spaces” and the rules of continuity and coherence that organize them into explorable terrain (10). A defining attribute of cult texts, hyperdiegesis invites expansion by official authors and fan creators alike, thus functioning as a space of contest and negotiation as well. The approach taken by Snyder, with the participation of Gibbons, is to treat the weakly serial Watchmen as a strongly serial text with a hyperdiegesis whose facts as established — not just the storyworld’s surface designs, but its history, society, and politics — are to be modified only at the adapter’s peril, risking the loss of audiences’ faith.

Watchmen (the film), in adopting its fanatically faithful approach to the visualization layer of the original, risks also replicating its sealed, hermetic qualities. “The cumulative effect of the astonishing level of attention,” writes Peter Y. Paik, “is a palpable sense of suffocation, so that the world of Watchmen ultimately takes shape in the form of a totality that has become wholly closed in upon itself.” (11) For Paik, the “constricting nature of this mortified reality” is Moore’s and Gibbons’s way of conveying the unique existential prison of Watchmen, “in which is ruled out any form of change other than an abrupt and global transformation of the very conditions of existence, such as would take place with the extinction of Homo sapiens.”

This special case of hyperdiegesis, then — in which a closed fictional universe is forced open, via translatory technologies of visualization, across a terminator dividing still comic art from moving cinema image — is one in which the authorial status of Moore and Gibbons is collapsed with that of Zack Snyder, and in turn with the world-manipulating powers of Doctor Manhattan and (in another register) Adrian Veidt. Just as Veidt alters global existence with his own bold intervention, so does Snyder enact a fundamental ontological violence to deform, remake, and relaunch Watchmen in a new medium.

Snyder’s decision to hew as closely as possible to the visual content and layout of the comic book had a number of strategic effects. By creating an elevated platform for the many contributions of Dave Gibbons, it accounted for Moore’s absence while smoothly installing a third partner, Snyder, as fair-minded referee whose task was less to achieve his own artwork than to render onscreen the comic’s nearest possible analog. His role can thus be understood as mediating an encounter between two media, bridging a gulf born both of form (comics versus movies) and of time (represented by the “new” of CGI).

The decision also made available to the production an archive of already-designed material, the extensive visual “assets” from which Watchmen is woven. More than simply a catalog of surfaces, the comic’s panels embed within themselves the history and operating principles of an alternate reality, a backdrop the production would otherwise have had to invent — placing the film in an inherently derivative status to the original. Going hyperfaithful with the adaptation deflected the production’s need to “top” its source design and instead assign itself the new mission of reverent translation.

At the same time, as I have argued, Snyder’s film risked getting stuck in a bubble of irrelevance, the strange half-life of the cult oddity, whose self-referencing network of meaning results (to outsiders) in the production of nonmeaning: a closed system. Preserving too exactly an inherited set of signs took the politically and mythologically overdetermined text of Watchmen and turned it into a “graphically” overdetermined movie, an affective state described by critics in terms like airless and inert.

From an auteurist point of view, going with a different ending may have been Snyder’s way of increasing the chance that his work would be taken as more than mere facsimile. From an industrial standpoint, dropping the squid may have seemed a way of opening up the story’s interpretations, making it available to a broader audience whose shared base of experience did not include giant teleporting squids, but most certainly did include visions of skyscrapers falling and cities smoldering.

“It seems that every generation has had its own reasons for destroying New York,” writes Max Page, tying our long history of visualizing that city’s destruction in film, television, and other media to a changing set of collective fears and preoccupations (12). From King Kong‘s periodic film rampages (1933, 1976, 2005) to Chesley Bonestell’s mid-century paintings of asteroid strikes and mushroom clouds, to nuclear-armageddon scenarios like Fail-Safe (1964) and 24 (2001-2010), the end of the city has been rendered and rerendered with the feverish compulsion of fetish: a standing investment of artistic resources in the rehearsal — and hence some meager control over the meanings — of apocalypse.

At the time Moore and Gibbons were creating Watchmen, the dominant strain in this mode of visualization had shifted from fears in the 1950s and 60s of atomic attack by outsiders to a sense in the 70s and 80s that New York City was rotting from within, its social landscape becoming an alien and threatening thing. The signifiers of this decline — “crime, drugs, urban decay” (13) — were amplified to extremes in Escape from New York (John Carpenter, 1981), shifted into the register of supernatural comedy in Ghostbusters (Harold Ramis, 1984), and refracted through superhero legend in Batman (Tim Burton, 1989).

The New York of Watchmen is divided into sharply stratified tribes, beset by street drugs, and prone to mob violence; moreover, the city stands in for a state of world affairs in which corrupt superpowers square off over the heads of balkanized countries whose diversity only lead to hostility — multiculturalism as nightmare, not the choral utopia of Coca-Cola’s “I Want to Teach the World to Sing” (1971) but the polyglot imbroglio of Blade Runner (1982).

Viewed this way (as following from a particular thesis about the nature of society’s ills), the original ending with the squid can be seen as the Tower of Babel story in reverse: a world lost in a confusion of differences becomes unified, harmonious, one. That this is achieved through an enormous hoax is the hard irony at the heart of Watchmen — a piece of existential slapstick, or to quote another Alan Moore creation, a “killing joke.”

One consequence of having so insistently committed to visual record simulations of New York’s demise was that the events of September 11 — specifically the burning and collapse of the World Trade Center — arrived as both a horrible surprise and a fulfillment of prophecy. The two towers had fallen before, in Armageddon and Deep Impact (both 1998), and the months after 9/11 were filled with self-analysis and recrimination by media suddenly conscious of their potential complicity, if not in the actual act of terrorism, then in its staging as fantasy dry-run.

Among its other effects, 9/11 brought to devastating life a conception of sheer urban destruction that had formerly existed only in the precincts of entertainment. It also crystallized — or enabled our government to crystallize — the enemies responsible, a shadowy network whose conveniently elastic boundaries could expand to encompass whole cultures or dilate to direct lethal interrogative force on individual suspects. The Bush administration’s response to the attacks, as played out in suppressions of liberty and free press in the U.S., in bellicose pronouncements of righteous vengeance in the world court, and ultimately in the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, was like a cruel proof of Veidt’s concept, conjuring into simultaneous existence a fearsome if largely fictional enemy and a “homeland” united in public avowal, if not in actual practice.

One might make the case that Moore and Gibbons in some way “predicted” 9/11 — not in the particulars of the destruction, but in its affective impact and corresponding geopolitical consequences. Just as the squid released in death a psychic shockwave, killing millions while leaving buildings untouched, so did the cognitive effects of the 9/11 attacks ripple outward: at first in a spectacular trauma borne viruslike on our media screens, later in the form of a post-9/11 mindset notable for its regressive conflation of masculinity and security (14). Ten years on, it is highly debatable whether U.S. actions after 9/11 resulted in a safer or more unified world; we seem in some ways to have ended up back where we started, poised at a tipping point of crisis, just as the concluding panels of Watchmen‘s circular narrative “leave in our hands” the decision to publish Rorschach’s journals and blow the hoax wide open. But in the initial, heady glow of late 2001 and early 2002, with the Abu Ghraib revelations (that blunt and pornographic proof of the enterprise’s rotten core) years away, it seemed briefly possible that the new reality we confronted might turn out to be “a stronger loving world.”

That mass deception underlies Veidt’s plan is, of course, another connection to 9/11, in the eyes of those who believe the attacks were carried out by the U.S. Government. Conspiracy theorizing around 9/11 coalesced so quickly it almost qualifies as its own subdiscipline of paranoid reasoning, rivaling perpetual motion and the assassination of JFK as one of the great foci of fringe scholarship. It would hardly be surprising if the original Watchmen was taken up by this movement as a piece of evidence before the fact, for as Stephen Prince observes, pre-9/11 films such as Gremlins (1984), The Peacemaker (1997), and Traffic (2000) have all been accused of embedding subliminal messages about the impending event. (15)

As a media text manufactured well after 9/11, Snyder’s adaptation faced a dual challenge: not simply whether and how to change the ending to something more narratively and conceptually streamlined, but how to negotiate showing the two towers, which by the logic of period were still standing in 1985, even an “alternative” one. The World Trade Center does not figure among the landmarks consumed by the energy wave, which in any case consumes a small amount of screen time (left unadapted is the famed series of full-sized splash pages that opens Watchmen‘s final chapter, an aftermath of panoramic carnage whose stillness builds creepily upon the static nature of the art). But the towers do appear in at least two shots, during the Comedian’s funeral and in the background of Veidt’s office. Both scenes were seized upon for commentary by fans as well as conspiracists. As one blogger wrote,

My interpretation was that Snyder was giving a nod to the fact that the terrible, horrible, completely implausible conclusion of Watchmen has, in fact, already happened. The 9/11 attacks were a lot like the finale of the book — alien, unexpected, tragic, unifying — only without the giant squid. … Snyder felt he had to at least address that in some way. The allusions to the towers were a way of saying, “Okay, I get it. This has already happened.” (16)

The effect of 9/11 on cinematic representation has been to turn either choice — to show or not to show — into a significant decision. For a time following 9/11, studios scrambled to scrub the twin towers from the frame, in films like Zoolander, Serendipity, and Spider-Man. (17) Later appearances of the World Trade Center took on inevitable thematic weight, in films such as Gangs of New York and Munich — presumably a motivation shared by Snyder’s Watchmen, which uses the towers to underscore rhetorical points.

Adaptation is not a new concern for film and media studies, any more than it is a new phenomenon in the industry; as Dudley Andrew points out, “the making of film out of an earlier text is virtually as old as the machinery of cinema itself.” (18) One of the most “frequent and tiresome” discussions of adaptation, Andrew goes on, is the debate over fidelity versus transformation — the degree to which an adapted work succeeds, or suffers, based on its allegiance to an outside source. As tired as this conversation might be, however, Watchmen demonstrates that it continues to structure adaptation both at the level of production (in which Snyder and his crew boast of their painstakingly reverence for the original) and of reception (in which fans analyze the film according to its treatment of Moore and Gibbons). In this way, controversy over the squid’s disappearance goes hand-in-hand with responses to the hyperfaithful visual setting, as referenda on Snyder’s approach; love it or hate it, we cannot resist reading the film of Watchmen alongside the comic book.

But a time of new media gives rise to new questions about adaptation. Whether we understand the mores of contemporary blockbuster filmmaking in terms of ubiquitous special effects, the swarm deployment of paratexts and transmedia, or the address of new audience formations through new channels, Watchmen reminds us that, in an era of new media, all texts mark adaptations in the evolutionary sense, forging recognizability across an alien landscape and establishing continuities with beloved texts — and the media they embody — across the digital divide.

Works Cited

1. Dave Gibbons, Chip Kidd, and Mike Essl, Watching the Watchmen(London: Titan Books, 2008), 28-29.

2. Peter Aperlo, Watchmen: The Film Companion (London: Titan Books, 2009), 16.

3. David Hughes, “Who Watches the Watchmen? How the Greatest Graphic Novel of All Time Confounded Hollywood,” in The Greatest Sci-Fi Movies Never Made (Chicago: A Cappella Books, 2001), 144.

4. Hughes, 147.

5. Aperlo, 26.

6. Kristin Thompson, The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

7. Jonathan Gray, Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and other Paratexts (New York: NYU Press, 2010).

8. Aperlo, 38.

9. Aperlo, 62.

10. Matt Hills, Fan Cultures (London: Routledge, 2002), 137-138.

11. Peter Y. Paik, From Utopia to Apocalypse: Science Fiction and the Politics of Catastrophe (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 50.

12. Max Page, The City’s End: Two Centuries of Fantasies, Fears, and Premonitions of New York’s Destruction (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 7.

13. Page, 144.

14. Susan Faludi, The Terror Dream: Fear and Fantasy in Post-9/11 America (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2007).

15. Stephen Prince, Firestorm: American Film in the Age of Terrorism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 78-79.

16. Seth Masket, “The Twin Towers in ‘Watchmen’ (http://enikrising.blogspot.com/2009/03/twin-towers-in-watchmen.html), accessed January 27, 2011.

17. Prince, Firestorm, 79.

18. Dudley Andrew, “Adaptation,” in Film Adaptation, Ed. James Naremore (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2000), 29.