As part of a larger project I’m preparing on “blueprint culture” — fan subcultures devoted to drawing, drafting, charting, mapping, and playing the worlds of science-fiction media — here is a brief history, excerpted from my book manuscript on special effects and transmedia, of Franz Joseph and the Starfleet Technical Manual he created in 1975.

One man in particular would dominate Star Trek’s design-oriented fandom in the 1970s. Though not a fan himself, Franz Joseph Schnaubelt was the first to awaken a broad base of fans to the pleasures of charting and extending Star Trek’s diegetic backdrop. By the same token, Schnaubelt brought to the attention of the show’s license holders the enormous profit potential of Trek manufacturing: first through supplementary materials expanding on the Trek universe, then through relaunching Trek as a storytelling franchise.

Schnaubelt, who in his professional life went by the name Franz Joseph, was born in Chicago in 1914. A designer and draftsman, Joseph began working at the aeronautical and military research firm General Dynamics in 1941, drawing up plans of seaplanes and fighter planes. “For being a man who was vehemently opposed to war,” Joseph’s daughter Karen Dick writes, he “certainly worked on some of the most formidable war machinery of the ‘40s, ‘50s, and ‘60s.”[i] Laid off in 1969, Joseph entered an early retirement that ended when his attention turned to Trek – not as entertainment, but as intellectual exercise. During the original series’ run, Joseph and Karen had watched the show together, but her passion outstripped his (he considered Star Trek only slightly superior to Lost in Space). In April 1973, Karen took her father to the inaugural meeting of the San Diego branch of the Star Trek Association for Revival (S.T.A.R.).[ii] The fans gathered there brought with them homemade models of Trek equipment such as communicators and phasers. According to Joseph, the ersatz props “were made out of cardboard, balsa wood, tape, wiring, glue, and paint and, for college kids … the workmanship was pretty bad any way you looked at it.”[iii] A former Cub Scout director, Joseph told the amateur craftsmen he thought “they could do better.”[iv] When they asked for assistance, Joseph agreed to bring his own professional training to bear.

Working from more than 800 film clips Karen had amassed, Joseph began to draft blueprints of the props, basing his work on a principle of architectural draftsmanship in which schematic drawings are projected into 3D views. Joseph reversed this, moving “from picture to plan” rather than from plan to picture.[v] In this sense, he inverted the process by which Matt Jefferies, a decade earlier, designed Trek’s sets and spacecraft: Jefferies would prepare both top-down plans and elevations – 3D views, some in color – showing how the finished object would look from camera viewpoint. According to Joseph,

I could take a picture of an enemy airplane and, as long as there was something on the airplane, or in the picture, that permitted me to determine the scale or make a fairly good judgment of the scale, then I would simply reverse the procedure and draw the plans of the airplane in that picture. This is what I was doing with the Star Trek slides. I drew the plans of the communicator, and then plans of the hand phaser and the pistol phaser.[vi]

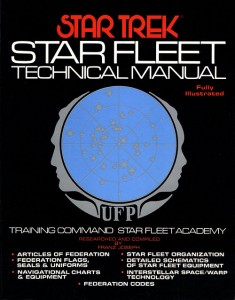

When Karen’s friends saw the drawings, Joseph said, they “went wild over them. They wanted a lot more. They wanted everything. They made a whole list of stuff they wanted to see and I decided, well, I would do it if there was an interest in it.”[vii] When Joseph examined the lists, he realized that the fans were asking for “a ‘technical’ manual,” and set to work drawing up a comprehensive mechanical anatomy of Trek’s diegetic contents (Figure 3).[viii] From Lincoln Enterprises, the memorabilia vendor run by Roddenberry and Majel Barrett, Karen obtained a set of Matt Jefferies’s drawings of the Enterprise, the Galileo shuttlecraft, and the shuttledeck. “From those sketches and those in Whitfield’s book [The Making of Star Trek],” Joseph “laid the drawing out, scaled and sized it, and made a drawing of the Enterprise.”[ix] He then departed for the first time from canon, extrapolating a new type of Starfleet vessel – a massive warship called the Dreadnaught, which rearranged elements of the Enterprise configuration. Joseph topped off this initial set of drawings with a pattern for the standard Starfleet uniform, again demonstrating the seamless slippage among visual effects and more concrete elements such as sets, costumes, and props.

In the course of preparing the technical manual, Joseph decided it would be necessary to map the Enterprise’s internal layout. This was because the fan community

wanted bridge stations and other things concerned with the interior of the Enterprise, which did not exist except in a book or in somebody’s mind as a throwaway line. So it became rather obvious that I would have to lay out the Enterprise far enough to get to those areas – to see whether I could make drawings. This is how the Enterprise blueprints came about – in the middle of making the technical manual – they were primarily an afterthought.[x]

In “lofting” the ship, however, he discovered several errors in scale and perspective, most stemming from the change from 203 to 430 personnel (and a corresponding change in length from 180 to 947 feet) made by Roddenberry and Jefferies during preproduction on the original series. He also noticed that the bridge was 36 degrees out of alignment with the rest of the saucer – throughout the series, Captain Kirk had been facing slightly to the left of the ship’s angle of travel, a mistake that had to do with the producers’ need to create dramatic visual compositions by placing the “turbolift” elevator so it was not directly behind the captain’s chair. Drafting the technical manual and ship blueprints was, then, largely a matter of reconciling the “imaginary” object of the Enterprise miniature with the “real” object of sets such as the bridge, sickbay, and engineering, explaining in graphic form how exterior and interior aspects of the Enterprise fit together into a coherent whole. In this sense, Joseph’s work might be described as operationalizing the Kuleshov effect, tying down and standardizing relationships created through editing. The technical materials upon which design-oriented fandom thrives – blueprints, models, hand-crafted props – thus serve an essentially conservative function, knitting together loose seams of an imperfectly-manufactured diegetic reality, as opposed to the exploding/perverting of officially preferred meanings that occurs in fan fiction (particularly slash).

Nevertheless, his technical productions did ultimately bring him into conflict with Trek’s legal authors. Interviews with Joseph demonstrate the care he took not to step on the toes of Trek’s copyright holders; from the start, he corresponded with Roddenberry and Paramount executives, sending them samples of his work. At the same time, Joseph’s encounters with the fan community convinced him there was substantial interest in his technical drawings, a site of imaginative investment as well as potential profit. By May 14, 1973 – only a month after the S.T.A.R. meeting that inspired the project – Joseph, having completed a dozen drawings, contacted Roddenberry and received a go-ahead. Roddenberry hinted that Lincoln Enterprises would market the drawings once Joseph completed them. For a brief time, Roddenberry even employed Joseph as technical consultant and designer on a new science-fiction series he was then developing, Planet Earth.

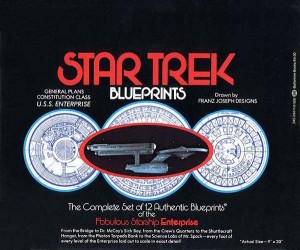

But months later, with a major Trek convention approaching, Joseph had still not received official permission to sell his work. Bypassing Roddenberry, he made a one-time deal with Paramount to sell the “General Plans” (the Enterprise blueprints) at the upcoming convention. Equicon 1974 took place in Los Angeles from April 12-14. Of the 500 copies of the General Plans Joseph had prepared, 410 sold immediately; 450 requests for additional copies were taken on postcards. Paramount, which received Joseph’s royalty check shortly thereafter, sensed it was on to something, and began negotiating for a mass-market release of both the General Plans and the still-growing Technical Manual. The results exceeded all expectations. The blueprints went on sale across the nation on May 24, 1975, selling out within two hours. By May 28, 50,000 additional copies had sold, prompting Ballantine to print 100,000 more. In July the New York Times marveled,

It lives! There’s one publication that’s been selling so furiously in book stores during recent weeks that it would be included on the list [of bestsellers] above except for one fact. It’s not a book. “Star Trek Blueprints” is a set of 12 reproductions by Franz Joseph Schnaubelt showing “every foot of every level of the fabulous starship Enterprise.” Since mid-May Ballantine Books has sold 150,000 sets, enclosed in a plastic and leatherette portfolio, at $5. This week it goes back to press for 100,000 more.[xi]

The blueprints continued to sell strongly throughout the summer, reaching 10th on the paperback bestseller list and receiving a fourth printing in October. Meanwhile, interest in Franz Joseph’s other creation, the Technical Manual, was growing: at a time when a typical first printing of a Trek-related publications might run 20,000, Ballantine Books planned an initial run of 450,000. Both the General Plans and the Technical Manual ended up as bestsellers.

Although he found the widest audience, Joseph was by no means the first or only producer of design-oriented Trek material. In addition to the substantial body of such work that went on unremarked in bedrooms and basement workshops, many fans printed blueprints and manuals and sold them at conventions and through mail order. Geoffrey Mandel’s Starfleet Handbook, for example, came out in September 1974 and featured “schematics of the phaser, communicator, tricorder, and shuttlecraft.”[xii] Nevertheless, Franz Joseph’s creations inspired numerous others throughout the mid- and late 1970s to map the fantasy world of Trek in exacting detail through blueprints of the bridge, K-7 Space Station, and Klingon and Romulan cruisers. The success of the General Plans and Technical Manual led to a string of similar publications at the mass-market level, and constituted an access point for fans wishing to join the ranks of professionals: The Star Fleet Medical Reference Manual, published in 1977, featured the work of Geoffrey Mandel and Doug Drexler (who would later go on to create Christopher Pike, Commanding and other imagery for the “Ships of the Line” calendars). The popularity of Joseph’s technical materials arguably influenced the development of the “Star Trek Poster Magazine,” whose first issue came out in September 1976, and the Trek “Fotonovel” series, both of which showcased Trek’s spectacular visuals through color reproductions of film frames.[xiii] This trend would eventually lead to a series of official Trek publications such as Mr. Scott’s Guide to the Enterprise, as well as technical manuals for spinoff series The Next Generation and Deep Space Nine.[xiv] With the growth of the personal-computer industry, software products such as the Interactive Guide to the Enterprise and Starship Creator joined the lineup.

Franz Joseph himself, however, did not go on to do more Trek projects. In part this was due to a series of illnesses affecting both him and his wife; but the larger obstacle seems to have been caused by Gene Roddenberry and Paramount themselves, who, during Trek’s pop-culture renaissance, were hard at work on relaunching the Star Trek franchise. In the early 1970s, Roddenberry assured Joseph that development of the General Plans and Technical Manual could continue unimpeded because Trek was, to all intents and purposes, a dead property. “Before I started seriously on the Manual,” Joseph said, “I had talked to Gene, Paramount, NBC, and Ballantine Books, and they all assured me that the Star Trek TV series was dead, it would not go back into production.”[xv] But the show had left a uniquely profitable corpse in the form of “the seventy-nine jewels,” as industry insiders called the original series, which continued to earn revenue through constant rebroadcast. The syndicated series was profitable in a secondary, subcultural sense, as Joseph himself acknowledged: “the reruns were maintaining continued fan interest, and gaining new fans every year. So I felt it was all right if I made the manual. It was something the original series never had, Gene wanted me to go ahead and finish it, and Ballantine was interested in publishing it.”[xvi]

[ii] Paul Newitt, “An Interview with Franz Joseph” (June 1984), <http:www.trekplace.com/fj-fjnewitt01.html>, accessed 18 June 2005.

[viii] Newitt, “An Interview with Franz Joseph.”

[x] Gerry Williams and Penny Durrans, “These Will Be A Reality Sooner than You Think.”

[xi] “Paper Back Talk,” New York Times (13 July 1975), 210.

[xii] Joan Marie Verba, Boldly Writing: A Trekker Fan and Zine History, 1967-1987, 2nd Ed. (Minnesota: FTL Publications, 2003), 17.

[xiii] Lynn Simross, “Fotonovel: The Movie-Picture Book,” Los Angeles Times (18 September 1978), OC_B1.

[xiv] Shane Johnson, Mr. Scott’s Guide to the Enterprise (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1989); Rick Sternbach and Michael Okuda, Star Trek: The Next Generation Technical Manual (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1991); Herman Zimmerman, Rick Sternbach, and Michael Okuda, The Deep Space Nine Technical Manual (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1998).

[xv] Newitt, “An Interview with Franz Joseph.”