Back in the 70s, like most kids who grew up middle-class and media-saturated in the U.S., I lived for the blocks of cartoons that aired after school and on Saturday mornings. From Warner Brothers and Popeye shorts to affable junk like Hong Kong Phooey, I devoured just about everything, with the notable exception of Scooby Doo, which I endured with resigned numbness as a bridge between more interesting shows. (Prefiguring my later interest in special effects both cheesy and classy, I was also nutty for the live-action Filmation series the networks would occasionally try out on us: cardboard superhero morality plays like Shazam! and Isis, as well as SF-lite series Ark II, Space Academy, and Jason of Star Command, which was the Han Solo to Space Academy‘s Luke Skywalker.)

Nowadays, as a fancypants professor of media studies who teaches courses on animation and fandom, I have, I suppose, moved on to a more mature appreciation of the medium’s possibilities, just as animation itself has found a new cultural location in primetime fare like Family Guy, South Park, and CG features from Pixar and DreamWorks that speak simultaneously to adult and child audiences. But the unreformed ten-year-old in me is still drawn to kids’ cartoons – SpongeBob is sublime, and I rarely missed an episode of Bruce Timm’s resurrection of Superman from the 1990s. This week I had a look at the new CW series, The Spectacular Spider-Man (Wiki rundown here; Sony’s official site here), and was startled both by my own negative response to the show’s visual execution and my realization that the transmedia franchise has passed me by while I was busy with others things … like going to graduate school, getting married, and buying a house. Maybe the photographic evidence of a youthful encounter that recently turned up has made me sensitive to the passage of time; whatever the cause, the new series came as a shock.

First, the visual issue. It’s jolting how crude the animation of the new Spider-Man looks to my eye, especially given my belief that criticisms of this type are inescapably tied to generational position: the graphics of one era seem trite beside the graphics of another, a grass-is-always-greener perceptual mismatch we all too readily misrecognize as transhistorical, inherent, beyond debate. In this case, time’s arrow runs both ways: The garbage kids watch today doesn’t hold a candle to the art we had when I was young from one direction, Today’s shows [or movies, or music, or baseball teams, etc.] are light-years beyond that laughable crap my parents watched from the other. Our sense of a media object’s datedness is based not on some teleological evolution (as fervently as we might believe it to be so) but on stylistic shifts and shared understandings of the norm — literally, states of the art. This technological and aesthetic flux means that very little cultural material from one decade to another escapes untouched by some degree of ideological Doppler shift, whether enshrined as classic or denigrated as obsolete, retrograde, stunted.

Nevertheless, I have a hard time debating the evidence of my eyes – eyes here understood as a distillation of multiple, ephemeral layers of taste, training, and cultural comfort zoning. The character designs, backgrounds, framing and motion of The Spectacular Spider-Man seem horribly low-res at first glance: inverting the too-many-notes complaint leveled at W. A. Mozart, this Spider-Man simply doesn’t have enough going on inside it. Of course, bound into this assessment of the cartoon’s graphic surface is an indictment of more systemic deficits: the dialogue, characterization, and storytelling seem thin, undercooked, dashed off. Around my visceral response to the show’s pared-down quality there is a whiff of that general curmudgeonly rot (again, one tied to aging — there are no young curmudgeons): The Spectacular Spider-Man seems slangy and abrupt, rendered in a rude optical and narrative shorthand that irritates me because it baffles me. I see the same pattern in my elderly parents’ reactions to certain contemporary films, whose rhythms seem to them both stroboscopically intense and conceptually vapid.

The irony in all this is that animation historically has been about doing more with less — maximizing affective impact, narrative density, and thematic heft with a relative minimum of brush strokes, keyframes, cel layers, blobs of clay, or pixels. Above all else, animation is a reducing valve between the spheres of industrial activity that generate it and the reception contexts in which the resulting texts are encountered. While the mechanism of the live-action camera captures reality in roughly a one-to-one ratio, leaving only the stages of editing and postproduction to expand the labor-time involved in its production, animation is labor- and time-intensive to its very core: it takes far longer to produce one frame than it takes to run that frame through the projector. (This is nowhere clearer than in contemporary CG filmmaking; in the more crowded shots of Pixar’s movie Cars, for example, some frames took entire weeks to render.)

As a result, animation over the decades has refined a set of representational strategies for the precise allocation of screen activity: metering change and stasis according to an elaborate calculus in which the variables of technology, economics, and artistic expression compete — often to the detriment of one register over another. Most animation textbooks introduce the idea of limited animation in reference to anime, whose characteristic mode of economization is emblematized by frozen or near-frozen images imparted dynamism by a subtle camera movement. But in truth, all animation is limited to one degree or another. And the critical license we grant those limitations speaks volumes about collective cultural assumptions. In Akira, limitation is art: in Super Friends (a fragment of which I caught while channel-surfing the other day and found unwatchably bad), it’s a commercial cutting-of-corners so base and clumsy as to make your eyeballs burst.

It’s probably clear that with all these caveats and second-guessings, I don’t trust my own response to The Spectacular Spider-Man‘s visual sophistication (or lack of it). My confidence in my own take is further undermined by the realization that the cartoon, as the nth iteration of a Spider-Man universe approaching its fiftieth year, pairs its apparent crudeness with vast complexity: for it is part of one of our few genuine transmedia franchises. I’ve written on transmedia before, each time, I hope, getting a little closer to understanding what these mysterious, emergent entities are and aren’t. At times I see them as nothing more than a snazzy rebranding of corporate serialized media, an enterprise almost as old as that other oldest profession, in which texts-as-products reproduce themselves in the marketplace, jiggering just enough variation and repetition into each spinoff that it hits home with an audience eager for fresh installments of familiar pleasures. At other times, though, I’m less cynical. And for all its sketchiness, The Spectacular Spider-Man offers a sobering reminder that transmedia superheroes have walked the earth for decades: huge, organic archives of storytelling, design networks, and continuously mutating continuity.

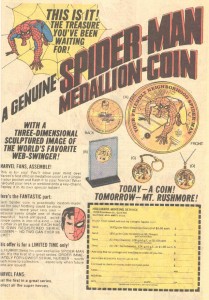

Geoff Long, who has thought about the miracles and machinations of transmedia more extensively and cogently than just about anyone I know, recently pointed out that we live amid a glut of new transmedia lines, most of which — like those clouds of eggs released by sea creatures, with only a lottery-winning few lucky enough to survive and reproduce — are doomed to failure. Geoff differentiates between these “hard” transmedia launches and more “soft” and “crunchy” transmedia that grow slowly from a single, largely unanticipated success. In Spider-Man, Batman, Superman and the like, we have serial empires of apparent inexhaustibility: always more comic books, movies, videogames, action figures to be minted from the template.

But the very scale of a long-lived transmedia system means that, at some point, it passes you by; which is what happened to me with Spider-Man, around the time that Venom appeared. This symbiotic critter (I could never quite figure out if it’s a sentient villain, an alter-ego of Spidey, or just a very aggressive wardrobe malfunction) made its appearance around 1986, approximately the same time that I was getting back into comic books through Love and Rockets, Cerebus, and the one-two punch of Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns and Moore’s and Gibbons’s Watchmen. Venom represented a whole new direction for Spider-Man, and, busy with other titles, I never bothered to do the homework necessary to bind him into my personal experience of Spider-Man’s diegetic history. Thus, Sam Raimi’s botched Spider-Man 3 left me cold (though it did restage some of the Gwen Stacy storyline that broke my little heart in the 70s), and when Venom happened to show up on the episode of Spectacular Spider-Man that I watched, I realized just how out of touch I’ve become. Venom is everywhere, and any self-respecting eight-year-old could probably lecture me on his lifespan and dietary habits.

Call this lengthy discourse a meditation on my own aging — a bittersweet lament on the fact that you can’t stay young forever, can’t keep up with everything the world of pop entertainment has to offer. Long after I’ve stopped breathing, the networked narratives of my favorite superheroes and science-fiction worlds will continue to proliferate. My mom and dad can enjoy this summer’s Iron Man without bothering over the lengthy history of that hero; perhaps I’ll get to the same point when, as an old man one day, I confront some costumed visual effect whose name I’ve never heard of. In the meantime, Venom oozes virally through the sidechannels and back-alleys of Spider-Man’s mediaverse, popping up in the occasional cartoon to tease me — much as he does the eternally-teenaged, ever-tormented Peter Parker — with a dark glimpse of my own mortality, as doled out in the traumas of transmedia.