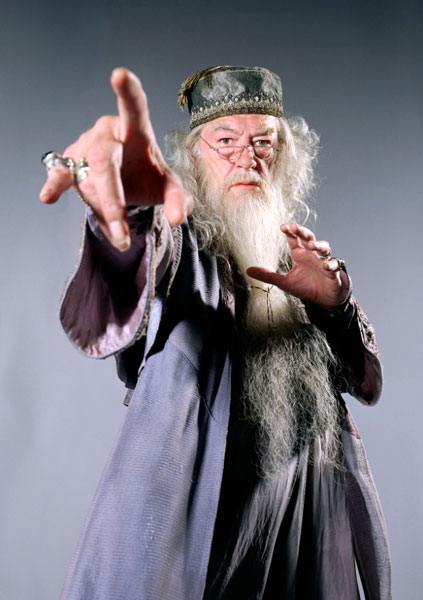

I was all set to write about J. K. Rowling’s announcement that Albus Dumbledore, headmaster of Hogwarts, was gay, but Jason Mittell over at JustTV beat me to it. Rather than reiterating his excellent post, I’ll just point you to it with this link.

Here’s a segment of the comment I left on Jason’s blog, highlighting what I see as a particularly odd aspect of the whole event:

On a structural level, it’s interesting to note that Rowling is commenting on and characterizing an absence in her text, a profound lacuna. It’s not just that Dumbledore’s queerness is there between the lines if you know to read for it (though with one stroke, JKR has assured that future readers will do so, and probably quite convincingly!). No, his being gay is so completely offstage that it’s tantamount to not existing at all, and hence, within the terms of the text, is completely irrelevant. It’s as though she said, “By the way, during the final battle with Voldemort, Harry was wearing socks that didn’t match” or “I didn’t mention it at the time, but one of the Hogwarts restrooms has a faucet that leaked continuously throughout the events of the seven books.” Of course, the omission is far more troubling than that, because it involves the (in)visibility of a marginalized identity: it’s more as though she chose to reveal that a certain character had black skin, though she never thought to mention it before. While the move seems on the surface to validate color-blindness, or queer-blindness, with its blithe carelessness, the ultimate message is a form of “stay hidden”; “sweep it under the rug”; and of course, “Don’t ask, don’t tell.”

We’ve got two more movies coming out, so of course it will be interesting to see how the screenwriters, directors, production designers, etc. — not to mention Michael Gambon — choose to incorporate the news about Dumbledore into the ongoing mega-experiment in cinematic visualization. My strong sense is that it will change things not at all: the filmmakers will become, if anything, scrupulously, rabidly conscientious about adapting the written material “as is.”

But I disagree, Jason, with your contention that Rowling’s statement is not canonical. Come on, she’s the only voice on earth with the power to make and unmake the Potter reality! She could tell us that the whole story happened in the head of an autistic child, a la St. Elsewhere, and we’d have to believe it, whether we liked it or not — unless of course it could be demonstrated that JKR was herself suffering from some mental impairment, a case of one law (medical) canceling out another (literary).

For better or worse, she’s the Author — and if that concept might be unraveling in the current mediascape, all the more reason that people will cling to it, a lifejacket keeping us afloat amid a stormy sea of intepretation.