Here are preliminary notes for a brief guest lecture I’m giving tomorrow in Professor Maya Nadarni’s course “Anthropological Perspectives on Childhood and the Family.” The topic is Children at Play.

Introduction: my larger research project

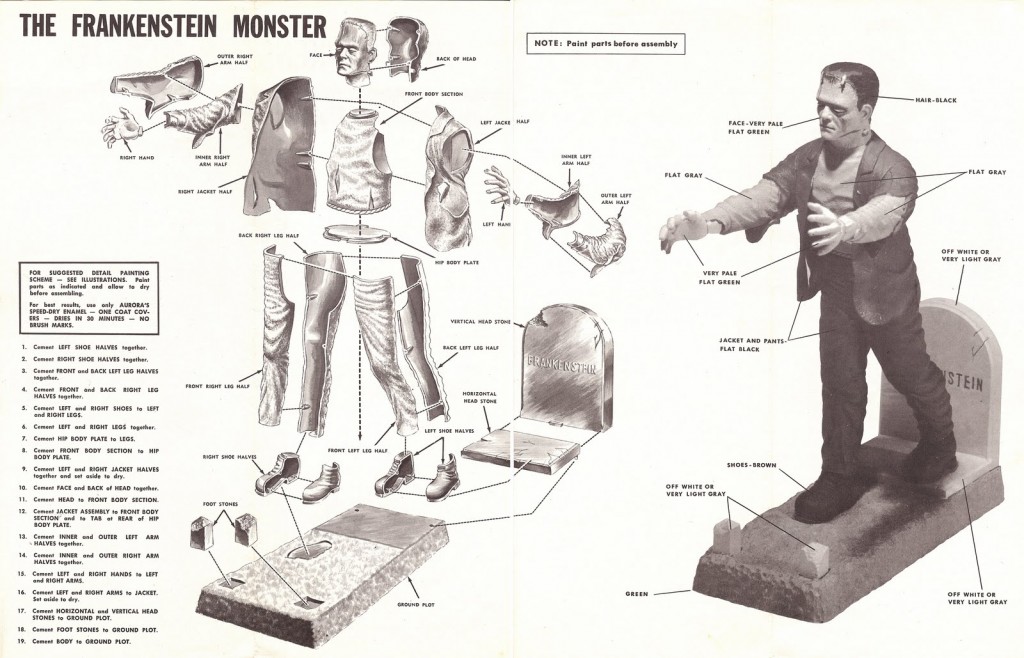

- fantastic-media objects, includes model kits, collectible statues, wargaming figurines, replica props: unreal things with material form

- these objects are an integral part of how fantastic transmedia franchises gain purchase culturally and commercial, as well as how they reproduce industrially

- particularly complex objects in terms of signification and value, mediation of mass and private, principles of construction, and local subcultures (both fan and professional) where they are taken up in different ways

- while these objects have been with us for decades, evolving within children’s culture, hobby cultures, gaming, media fandom, and special-effects practices, the advent of desktop fabrication (3D printing) paired with digital files portends a shift in the economies, ontologies, and regulation of fantastic-media objects

Jonathan Gray, Show Sold Separately: a counter-reading of toys and action figures

- examines Star Wars toys and action figures as examples of paratexts shaping interpretation of “main text”

- story of Lucas’s retention of licensing rights, considered risible at the time

- graphic showing that toys and action figures account for more profits than films and video games combined

- rescues “denigrated” category of licensed toys as “central to many fans’ and non-fans’ understandings of and engagements with the iconic text that is Star Wars. … Through play, the Star Wars toys allowed audiences past the barrier of spectatorship into the Star Wars universe.” (176)

- licensed toys provide opportunities “to continue the story from a film or television program [and] to provide a space in which meanings can be worked through and refined, and in which questions and ambiguities in the film or program can be answered.” (178)

- notes role of SW toys in sustaining audience interest during 1977-1983 period of original trilogy’s release

- transgenerational appeal of franchise linked to toys as transitional objects, providing a sense of familiarity in young fans’ identities

- current transmedia franchises include licensed objects as components of extended storyworlds

Case study in history: the objects of monster culture

- 1960s monster culture spoke to (mostly male and white) pre-teen and adolescent baby boomers

- mediated through Famous Monsters of Filmland (1958-), especially advertising pages from “Captain Company”

- Aurora model kits were key icons of this subculture: “plastic effigies”

- Steven M. Gelber: popularization of plastic kits represented “the ultimate victory of the assembly line,” contrasting with an earlier era of authentic creativity in which amateur crafters “sought to preserve an appreciation for hand craftsmanship in the face of industrialization.” (262-263)

- model kits provided young fans with prefab creativity, merging their own crafts with media templates; also opportunities for transformation (1964 model kit contest)