This is the third in a series of posts on a new project of mine exploring movie-monster fandom and “kid culture” in the U.S. from the early 1960s onward. My focus will be less on monster movies themselves than on the objects that circulated around and constituted the films’ public — and personal — presence: model kits, toys, games, and other paraphernalia. Approaching media culture through its object practices, I argue, reveals a dynamic space of production in which texts, images, and objects translate and transform one another in flows of commodities, collectibles, and creativity. [Previous posts can be found here.]

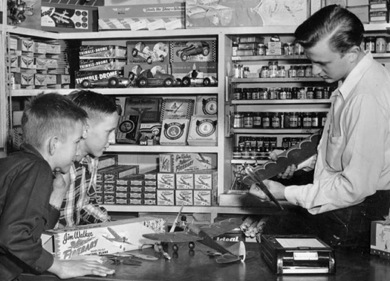

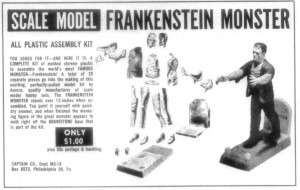

The line of monster models put out by Aurora starting in 1962 were not, of course, the first figure kits; neither were they the first scale plastic models. As Thomas Graham notes in his collectors’ guide Aurora Model Kits, the company’s first foray into the world of scale model kits was in 1952, with a line of airplanes. Other kits released by Aurora in its first decade of operation included automobiles, boats, submarines, tanks, and missiles. These subjects shared a set of qualities: they were based not on fictional, licensed properties but on existing real-world referents; not on organic, living beings (with the exception of figure kits, which I will discuss below) but on mechanical vessels; and, though they comprised a range of historical periods from antique cars (the WWI-era Stutz Bearcat) to the latest in mid-century aerospace experimentation (the Ryan X-13 Vertijet), favored transport technology and armaments from the two major global military conflicts.

This focus was unsurprising, given the circumstances of plastic kits’ emergence as a popular pastime in the U.S. after the end of World War II. The enormous social and economic changes following 1945 included a radical expansion of products geared to recreation, as factories and workforces were repurposed to drive an affluent North American economy (and a culture of advertising emerged in parallel to foment the necessary appetites). This prosperity played out simultaneously on two levels, one for parents and one for children; as Graham describes it, “Veterans from World War II and Korea resumed their lives, moving to the suburban world of ranch style homes with new Chevies, Fords and Studebakers parked in the car ports. Their kids rode bicycles, shot Daisy air rifles, watched Sky King on TV, listened to 45 rpm records, and read comic books. And they made model airplanes.” (5) As goods proliferated across the spheres of youth and adulthood, the toys of the former scaled down to cheaper, playable size the luxury items of the latter: cars in the garage were mirrored by model autos inside the house. Yet the objects of childhood supplied by mass culture also distorted and amplified the world of adults, condensing primal drives and half-repressed memories in material form: science-fiction serials, air-rifle weapons, and most of all the replication of wartime air- and seacraft in miniature suggest that children of the Baby Boom were awash not just in the detritus of overproductive industry but the solidified, visualized dreams — and nightmares — of the preceding generation.

In Hobbies: Leisure and the Culture of Work in America, Steven M. Gelber situates the postwar explosion of plastic kits against a longer history of crafting and collecting that dates from the late nineteenth century, when social and economic changes in the workplace led to a colonization of domestic space and time by the recognized and hence legitimized world of handicrafts. “Before about 1880 a hobby was a dangerous obsession,” he writes. “After that date it became a productive use of free time.” (3) For Gelber, the paradox of such activities is that they reproduce the attributes of labor, such as regimented time and the creation of commodities, in a domain that should ideally be distinct from, and uncorrupted by, such labor.

Hobbies are a contradiction; they take work and turn it into leisure, and take leisure and turn it into work. Like work, hobbies require specialized knowledge and skills to produce a product that has marketplace value (even if there is no thought of selling it). … Hobbies occupy the borderland that is beyond play but not yet employment. More than any other form of recreational activity, hobbies challenge the easy bifurcation of life’s activities into work and leisure. (23)

Hobbies, in this view, have the ideological effect of industrializing the home, and reconfiguring domestic subjects as subjects of domestic labor — bringing what might otherwise be an unruly and disobedient space into line with the values and beliefs of modern capitalist society. This essentially disciplinary function did not preclude the very real pleasures that could be obtained from, for example, sewing, stamp collecting, or needlepoint. In addition, hobbies could represent complex negotations with the economy, as when items of furniture built at home replaced those that would otherwise have been purchased at stores, or when, during the Great Depression of the 1930s, hobbies took on new ameliorative significance as an inexpensive way to fill the working hours denied to the unemployed. Finally, hobbies remixed gendered identities and skill sets in unusual ways, as women explored newly authorized forms of creative expression and men adapted to more domestic roles.

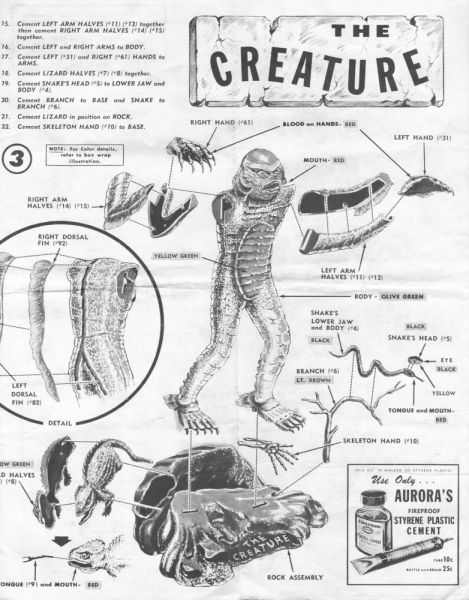

For Gelber, however, the rising popularity of kits in the postwar period was a less positive development. Citing a 1949 catalog for the hobby supplier American Handicrafts, Gelber notes the way in which kits — prepackaged sets of items for assembly into everything from pot holders and pottery to woven stools and Indian beads — “severely limited hobbyists’ creativity but greatly facilitated their productivity.” (262) Because one could only build a kit into its intended object, and because this process required nothing more than the following of instructions, kits represented a more blunt and dire industrialization of home spaces and subjects, turning hobbies — sometimes literally — into paint-by-numbers activities, “no more art than gluing together a plastic model was a craft.” (263)

The kit was the ultimate victory of the assembly line. Whereas craft amateurs had previously sought to preserve an appreciation for hand craftsmanship in the face of industrialization, kit hobbyists conceded production to the machine. They became the leisure-time equivalent of the apocryphal Ford worker who, as his last wish before retiring, requested permission to finish tightening the bolt he had been starting for the last thirty years. Kit assemblers did not dream of designing the product or forming its parts. It was enough that they could surpass the Ford worker’s wish and actually assemble the whole thing. Forty years of assembly line mentality had transformed the public’s understanding of personal agency from that of the artisan to that of a glorified factory worker. (262-263)

The worst thing about kits, in Gelber’s view, was that “the hobbyist did not have to engage the hobby at a higher level of abstraction.” DIY projects or handicrafts built from the ground up required a hobbyist to solve many problems ahead of time, exerting his or her individuality through the choice of object and materials, along with the tools and skills required. With kits, on the other hand, “There were no preliminary steps, no planning or organizing, no thinking about the process. In other words, the hobbyists did not have to engage the craft intellectually.” (262)

Gelber’s history of hobbies in America stops around 1950, at the dawn of the plastic-kit craze — a time that saw sales of plastic models grow from $44 million in 1945 to $300 million by 1953. His critical reading of the kit phenomenon brings up valid points: this transition to a new era both of industry and recreation marked a profound reconfiguration of longstanding, and much cherished, traditions. The same period saw the diminishment of certain knowledges and skills shared by a public base increasingly dependent on the prefabricated products of mass culture: manufacturing and distribution technologies that Bruno Latour, by way of Marx, has called “congealed labor.” And while, as we shall see, his derision of model-kit building as limited and artless pastime requiring no creative input from the assembler ignores the kinds of transformation, circulation, and sharing that would come to define object practices in 1960s horror fandom, it is easy to imagine the more generous readings that contemporary hobby culture, outside the scope of his book, might engender.

In the next installment, I will turn to the heyday of Aurora, from 1962-1977, and the line of monster kits that made it a success.

Works Cited

Gelber, Steven M. Hobbies: Leisure and the Culture of Work in America. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

Graham, Thomas. Aurora Model Kits. 2nd Ed. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 2006.