[This is the last of four posts counting down the final episodes of Battlestar Galactica. To see the others, click here.]

I’d meant to write my final entry in the “Counting Down Galactica” series before the airing of the finale on Friday night; a power outage in my neighborhood prevented me from doing so. Hence everything I’m about to say is colored by having seen the two-hour-and-eleven-minute conclusion, and spoilers lie in wait.

On the topic of spoilers, I know of a few ambitious souls (hi, Suzanne!) who are holding the finale in reserve, planning to watch it next week. Let me note how sympathetic I am toward, and dubious about the chances of, their or anyone’s ability to navigate the days ahead without having the ending spoiled. I haven’t even dared to visit Facebook yet, for fear of destabilizing my own still-coalescing thoughts on the experience; similarly, I won’t go near the various blogs I read. When I got up this morning, I turned on NPR’s Weekend Edition, only to find myself smack-dab in the middle of a postmortem with Mary McDonnell. It was like coming out of hyperspace into an asteroid field, or — a more somber echo — waking on the morning of 9/11 to a puzzled voice on the radio saying, in perhaps our last moment of innocence, that pilot error seemed to be behind a plane’s freak collision with the World Trade Center.

Comparing BSG’s wrapup to the events of 9/11 might seem the nadir of taste, except that Galactica probably did more in its four seasons than any other media artifact besides 24 — I’m discounting Oliver Stone movies and the Sarah Silverman show — to process through pop culture the terrorist attacks and their corrosive aftereffects on American psychology and policy. It became, in fact, an easy truism about the show, to the point where I’d roll my eyes when yet another commentator assured me that BSG was about serious things like torture and human rights. But then I shouldn’t let cynicism blind me to the good that stories and metaphors can do; I myself publicly opined that the season-two Pegasus arc marked a “prolapse of the national myth,” a moment at which BSG “strode right over the line of allegory to hold up a mirror in which the United States could no longer misrecognize its practices of dehumanization and torture.” And who am I to argue with the United Nations, anyway?

But maybe the more fitting connection is local rather than global, for losing power yesterday reminded me how absolutely dependent the current state of my life is on technology: the uninterrupted flow of internet, television, radio. My wife and I were able to brew coffee by plugging the pot into one remaining active outlet, and our cell phones enabled us to maintain contact with the outside world (until their batteries died). After that, it was leave the house and brave the bright outdoors and actual, face-to-face conversation with other human beings.

I bring this up because, in its final hours, BSG plainly announced itself as concerned, more than anything else, with the relationship between nature and technology — between humans and their creations. In retrospect, this dialectic is so obvious that I’m embarrassed to admit it never quite came into focus for me when the series was running. Sure, the initiating incident was a sneak attack by Cylons, a race of human-built machines who got all uppity and sentient on us. (Or maybe it’s the case that the rebellious Cylons descended from some other, ancient caste of Cylons — I’m not entirely clear on this aspect of the mythology, and consider it the show’s failing for not explaining it more clearly. But more about that in a moment.) Even in that first, fateful moment of aggression, though, the lines between us and them were blurred; in “reimagining” the 1970s series that was its precursor, Ronald D. Moore’s smartest decision — apart from scuffing up the mise-en-scene — was to posit Cylons who look like us; who think, feel, and believe like us. As the series wore on, this relationship became ever more intimate, incestuous, and uncomfortable, so that finally it seemed neither species could imagine itself outside of the other. It was differance, supplement, and probably several other French words, operationalized in the tropes of science fiction.

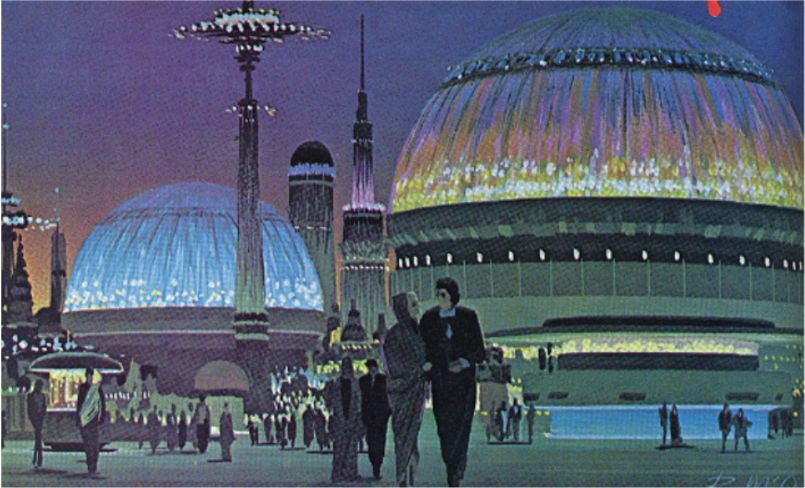

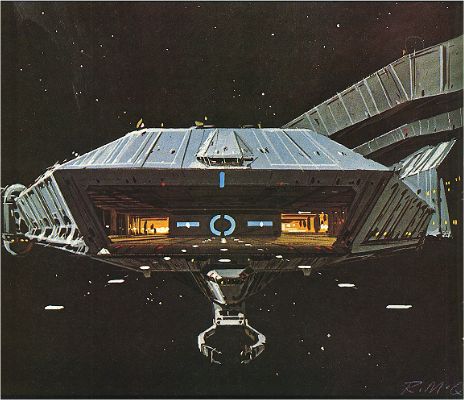

A more detailed textual analysis than I have the patience to attempt here would likely find in “Daybreak” an eloquent mapping of these tense territories of interdependent meanings. One obvious starting point would be the opposition between Cavil’s Cylon colony, a spidery, Gigeresque encrustation perched in a maelstrom of toxic-looking space debris, and the plains of Africa, evoked so emphatically in the finale’s closing third hour that I began to wonder if the story’s logic could admit the existence of any sites on Earth (or pseudo-Earth, as the story cutely frames it) that aren’t sunny, hospitable, and friendly. In this blunt binary I finally saw BSG’s reactionary (one might say luddite) ethos emerge in full flower: a decision on the undecidable, a brake on the sliding of signifiers. For all the show’s interest in hybrids of every imaginable flavor, it did finally come down to a rejection of technology, signaled most starkly in Lee Adama’s call to “break the cycle” by not building more cities — and the sailing of Galactica and her fleet into the sun. Even as humans and Cylons decide to live together (and, it’s suggested in the coda, provide the seed from which contemporary civilization sprouted), it seems to me the metaphor has been settled in humanity’s favor.

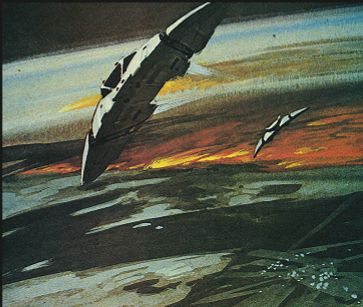

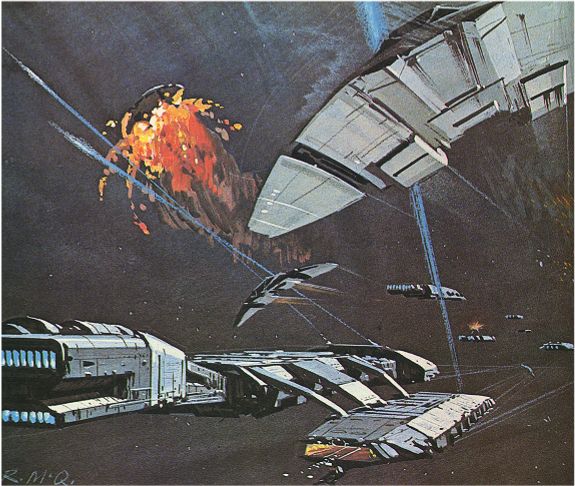

That’s fine; at least the show had the courage to finally call heads or tails on its endless coin-flipping. Interesting, though, that the basic division over which the narrative obsessed was reflected formally in the series’ technical construction and audience reception. I refer here to a dialectic that emerged late in the show’s run, between visual effects and everything else — between space porn and character moments. Reading fan forums, I lost count of the number of times BSG was castigated by some for abandoning action sequences and space battles, only to be countered by another group tut-tutting along the lines of This show has never been about action; it’s about the people. For what it’s worth, I’m firmly in the first camp (as my post last week demonstrates): the best episodes of Galactica were those that featured lots of space-set action (the Hugo-winning pilot, “33”; “The Hand of God”; most of the first season, for that matter, and bright moments sprinkled throughout the rest of the series). Among the worst were those that confined themselves exclusively to character interaction, such as “Black Market,” “Unfinished Business,” and most of the latter half of season four.

It’s not that the show was ever poorly written, or the characters uninteresting. But it did seem for long stretches to develop an allergy to action, with the result a bifurcated structure that drove some fans crazy. Much like the pointless squabbles around Lost, whose flashback structure still provokes some to shout “filler episode!” where others cry “Character development!”, debate on the merits of BSG too often devolved into untenable assertions about the antithetical relationship between spectacle and narrative, with space-porn fans lampooned as short-attention-span stimulus junkies and character-development fans mocked as pretentious blowhards. Speaking as a stimulus junkie and pretentious blowhard, I feel safe in pointing out the obvious: it’s hard to pull off compelling science fiction characters without some expertly integrated shiny-things-go-boom, while spaceships and ‘splosions by themselves get you nowhere. You need, in short, both — which is why BSG’s industrial dimension neatly homologized its thematic concerns.

I’m relieved that last night’s conclusion managed to reconcile the show’s many competing elements, and that it did so stirringly, dramatically, and movingly. I expected nothing less than a solid sendoff from RDM, one-half of the writing team behind perhaps the greatest series finale ever, Star Trek: The Next Generation‘s “All Good Things …” — but that’s not to say he couldn’t have screwed it up in the final instance. Indeed, if there is a worm in the apple, it’s my sneaking suspicion that the game was fixed: the four episodes leading up to “Daybreak” were a maddening mix of turgid soap opera and force-fed exposition, indulgent overacting and unearned emotion. It’s almost as though they wanted to lower our expectations, then stun us with a masterpiece.

I don’t know yet if “Daybreak” deserves that particular label, but we’ll see. In any case, there is something magical about so optimistic an ending to such a downbeat series. If the tortured soul of this generation’s Battlestar Galactica was indeed forged in the flames of 9/11 and the collective neurotic reaction spearheaded by the Bush administration, perhaps its happy ending reflects a national movement toward something better: the unexpected last-minute emergence, through parting clouds, of hope.