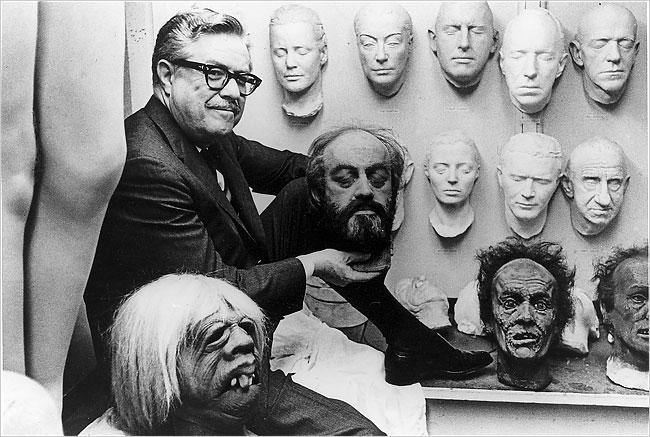

The death of Ralph McQuarrie on March 3 marked the loss of one of the key founders of the Star Wars franchise. McQuarrie’s authorial status within that vast transmedia network had for decades been subsumed under the cannibalizing sign of George Lucas’s “vision,” and just as the aging and death of the movies’ original actors has cleared the stage for such synthetic, endlessly replenishable replacements as the animated Clone Wars series and the Lego-ification of the saga, so McQuarrie’s demise signals the continued waning of a certain authentic (and temporally specific) artistry tied to, but distinct from, Lucas’s techno-auteurism. Below is an excerpt of my book manuscript on special effects and transmedia franchises, focusing on McQuarrie’s role in the previsualization of Star Wars.

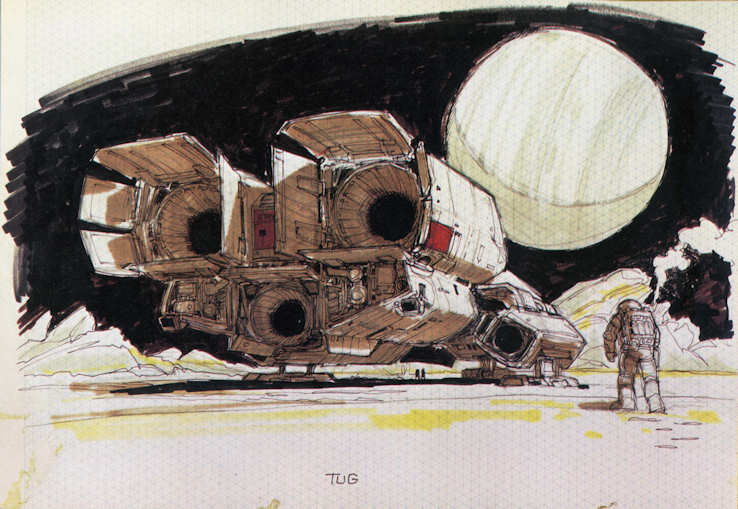

By summer 1974, the rough draft of what was then called The Star Wars ran 132 baffling pages. According to fellow director Michael Ritchie, to whom George Lucas showed the draft, “It was very difficult to tell what the man was talking about.”[i] Another friend, Hal Barwood, said the script “started off in horrible shape. … It was hard to discern there was a movie there. It was both kind of futuristic and funny and endearing and exciting all at once, but that combination of possibilities just didn’t dawn on us reading these words on the page.”[ii] Perhaps thinking back to his use of comic-book frames to sell the story treatment to Twentieth-Century Fox, Lucas acknowledged that “the concepts and characters he was devising were so bizarre that it was very difficult for anyone else to visualize them.” So he turned to a professional artist, Ralph McQuarrie, to portray The Star Wars in concrete visuals.[iii] McQuarrie was an industrial artist for Boeing Aircraft who came to prominence in Hollywood circles when he created illustrations of space flight for CBS’s coverage of the moon landings. Lucas hired him to paint “concept artwork” based on a handful of key images, including the ones below.[iv]

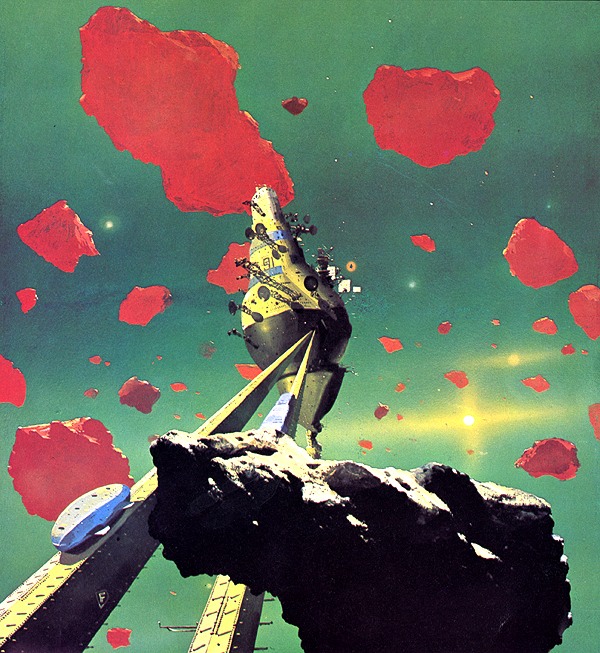

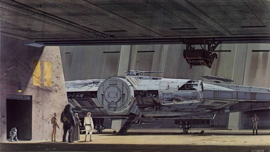

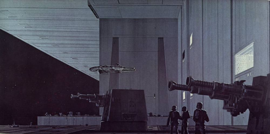

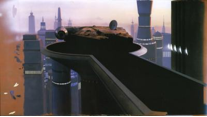

It is fair to say that without McQuarrie’s paintings, Star Wars would not have been made – or would at least have been a very different film. “George spent his money wisely on Star Wars by developing the art,” according to Lucasfilm production assistant Miki Herman. “Ralph McQuarrie’s paintings sold the movie to Fox.”[v] The paintings’ primary value was in leapfrogging past the limitations of time and budget to bring back images from Star Wars’ own future – its spectacular “money shots.” Done in opaque gouache and acrylic in widescreen aspect ratio, the art envisioned in arresting ways the central settings, character looks, and action beats of Lucas’s screenplay. Studio backers were all too pleased to find order amid the chaos; they were particularly reassured by the guarantee that the planned effects would be both technically achievable and splendidly unlike anything that had come before. Lucas “wanted the pictures to be idealist,” according to McQuarrie. “In other words, don’t worry about how things are going to get done or how difficult it might be to produce them – just do them how you’d like them to be.”[vi] Compared to the likely expense of producing the special effects they called for, the paintings cost nothing; yet that very lack of expense suggested that the images could be delivered on time and on budget. With the paintings, Lucas “wanted people to look and say, ‘Gee, that looks great, just like something on the screen.’”[vii]

McQuarrie’s artwork also helped to organize the production side of Star Wars. They defined the look of different characters as well as designs for costumes, settings, props, spaceships, planetary environments, and alien beings. McQuarrie is credited with originating key aspects of the film’s iconography, including Darth Vader’s breathing mask, the Jedi light sabers, the desert planet Tatooine with its two suns, R2-D2’s “three legs, a round swivel top on his cylindrical metal body, and a squat demeanor,”[viii] and certain spaceships. His designs helped lend the film its air of being a “used universe,” Lucas’s term for the scuffed and careworn quality of his retrograde future. More important, McQuarrie’s paintings provided a concrete reference point for the growing staff of casting directors, costume and set designers, storyboard artists, and special-effects craftspeople coming on board as ILM grew. At high levels, the artwork functioned as collaborative archive, enabling design teams to view, assess, and modify plans. At lower levels, the paintings coordinated the labor of draftsmen and model makers, providing a template for maintaining consistency in their output. Joe Johnston, credited with Effects Illustration and Design, was responsible for creating the extensive storyboards for Star Wars. “A lot of people ask me if I was the creator of the Star Wars spaceships, and I really wasn’t,” he has said. “Everyone else’s imagination was kind of funneled through mine and Ralph McQuarrie’s.”[ix] Similarly, John Stears, Special Production Mechnical Effects Supervisor, stated, “We had superb production illustrations by Ralph McQuarrie, and … the film adhered closely to them. A lot of the credit is due McQuarrie, as the look of the picture was due to him.”[x]

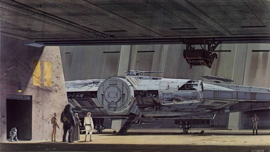

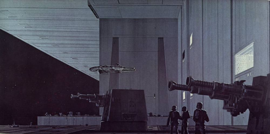

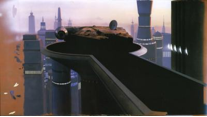

Artwork-to-shot comparisons

McQuarrie’s paintings acted as ersatz finished frames, which the production crew then reverse-engineered, building them from the ground up. The shots above, for example, duplicate almost exactly their corresponding preproduction art. Although McQuarrie went on to provide artwork for sequels The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi, he has expressed disappointment that his work for Lucas did not receive more credit in its own right. “I wonder if I haven’t been ripped off,” McQuarrie is quoted as saying. “But then, why should George pay me any more than he had to? He’s a pretty cool businessman.”[xi] Despite what these comments suggest, McQuarrie has never claimed that he alone originated the film’s visual elements, but rather developed them in consultation with Lucas. The fact remains, however, that many of the commonly cited examples of Star Wars’ incorporation of existing designs and motifs have their roots in McQuarrie’s artwork. He based the look of C-3PO, for example, on the robot Maria in Metropolis (Fritz Lang, 1927).

McQuarrie’s paintings acted as ersatz finished frames, which the production crew then reverse-engineered, building them from the ground up. The shots above, for example, duplicate almost exactly their corresponding preproduction art. Although McQuarrie went on to provide artwork for sequels The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi, he has expressed disappointment that his work for Lucas did not receive more credit in its own right. “I wonder if I haven’t been ripped off,” McQuarrie is quoted as saying. “But then, why should George pay me any more than he had to? He’s a pretty cool businessman.”[xi] Despite what these comments suggest, McQuarrie has never claimed that he alone originated the film’s visual elements, but rather developed them in consultation with Lucas. The fact remains, however, that many of the commonly cited examples of Star Wars’ incorporation of existing designs and motifs have their roots in McQuarrie’s artwork. He based the look of C-3PO, for example, on the robot Maria in Metropolis (Fritz Lang, 1927).

An even more significant contribution is the signature shot from near the end of the film: the rebel ceremony in which Luke Skywalker and his companions receive medals from Princess Leia. Frequently described as recycling the starkly symmetrical “mass ornament” of Nazi ranks from Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1935), the shot in Star Wars can be traced to McQuarrie through his preproduction painting, reproduced onscreen almost identically, albeit in reverse angle.

McQuarrie also contributed several matte paintings to the Star Wars films, literally inscribing his artwork into the movie. These paintings stand somewhere between design concept and finished frame, a transitional stage between different media:

Previz abounds in such intermediate objects – sketches, blueprints, crude models and maquettes, film tests, outtakes, work prints – weird hybrids seldom discussed in studies of film production, which devote attention and analysis to more stable, neatly classifiable forms. Yet the materials of previz deserve theorization precisely because they fill in the hidden interstices of production, marking incremental transformations from paper to screen and encompassing the totality of filmic manufacture. It is as though the production of motion pictures takes place on a darkened stage with spotlights picking out a few celebrated nodes of creation: in this corner, a director; in another, a writer and screenplay; and at the center, the final print distributed to theaters and serving thereafter as the nucleus of popular, journalistic, and academic discourse about the film. Bringing up the lights reveals that the stage is in fact crowded with materials and personnel whose work, while essential to the production, is effaced in order to maintain an orderly cosmology. This industrial mythology is anchored by the unifying figure of the film director.

I do not mean to suggest that previsualization (or the preproduction phase that is its larger backdrop) receives no public attention. Indeed, these technical activities and their associated narratives and imagery fuel a highly visible side industry of publication pitched to audiences fascinated with the process of making movies. Making-of books and behind-the-scenes documentaries are nothing new in Hollywood, and have to some extent been the focus of academic scrutiny for their role in what Steve Neale terms cinema’s “inter-textual relay”:

The institutionalized public discourse of the press, television and radio often plays an important part in the construction of [movies’ public] images. So, too, do the “unofficial,” “word of mouth” discourses of everyday life. But a key role is also played by the discourse of the industry itself, especially in the earliest phases of a film’s public circulation, and in particular by those sectors of the industry concerned with publicity and marketing: distribution, exhibition, studio marketing departments, and so on.[xii]

The “making-of” mania was particularly intense around Star Wars, echoing in discursive form the many tie-in objects – toys, model kits, pajamas, posters – used to promote the film. In 1977, Ballantine Books released an oversized portfolio of McQuarrie’s paintings, along with “The Art of Star Wars,” a book reprinting the screenplay alongside preproduction art, storyboards, and stills from the movie.[xiii] Such publications provided snapshots of an evolving production, freezing them like prehistoric insects in amber: a glimpse of Luke Skywalker as a woman; a McQuarrie painting of Han Solo as a Chewbacca-like monster; a scene or snippet of dialogue that failed to make the final cut. The material record of previz, riddled with gaps on their way to being closed, offers not just a glimpse of possibilities that might have been, but a relatively unvarnished perspective on the logics of appropriation and suppression by which Hollywood attempts to close a circle of authorial singularity and originality around its products. Because of its very in-betweenness, previz seems to mark a moment at which forces of ideological regulation are at their most contested and unstable. The promotional use of previsualization materials might therefore be seen as a clever strategy of containment, drawing attention to an impressive apparatus of visual-effects design in order ultimately to subsume it within the techno-auteur’s all-encompassing “vision.”

[i] Marcus Hearn, The Cinema of George Lucas (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2005), 147.

[v] Quoted in Pollock, Skywalking, 149.

[vi] Hearn, The Cinema of George Lucas, 83-84.

[vii] Quoted in Dale Pollock, Skywalking: The Life and Films of George Lucas (Hollywood, CA: Samuel French, 1990), 149.

[ix] Mandell, Paul. “Joe Johnston.” Interview. Cinefantastique 6.4/7.1 (1978), 78.

[x] Mandell, Paul. “John Stears.” Interview. Cinefantastique 6.4/7.1 (1978), 64.

[xi] Quoted in Pollock, Skywalking, 197.

[xii] Steve Neale, Genre and Hollywood (London: Routledge, 2000), 39.

[xiii] The first of these was Carol Titelman, ed., The Art of Star Wars (New York: Ballantine Books, 1979).

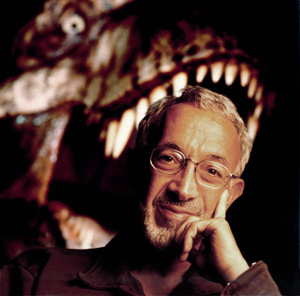

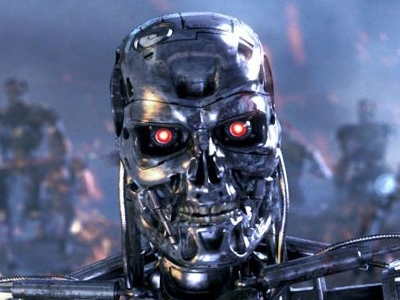

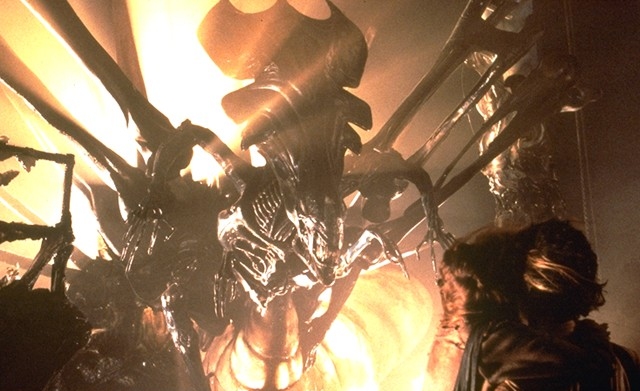

The Biology of Virtual Creatures: Unconventional Applications of a Science Education in Hollywood Special Effects

The Biology of Virtual Creatures: Unconventional Applications of a Science Education in Hollywood Special Effects