Watching Z pull himself eagerly along a shelf of books at our local library — thin tomes, the spine of each marked by a circular sticker whose color indicated the intended reading level — I allowed myself to hope that he will grow up bookish like me, drawn to the quiet hours one finds between a story’s pages, or the murmur of a parent’s voice reading aloud before bed. My mother read to me sometimes, but more consistently it was my oldest brother Paul, himself a highly intellectual, tense, and troubled young man with whom I got along not at all by day, but by night became my guide through lands of fantasy: The Hobbit, the Narnia books, A Wrinkle in Time and its remarkable, disquieting sequels. I would love to read these to Z, and more: Heinlein’s young adult novels, and Harry Potter, and E. Nesbit. But for now, I just whisper in the darkness of the nursery: shh shh shh, and it’s all right: waiting for the grape-flavored infant Advil to kick in and muffle his teething pain, our story a more simple and shared one of comfort in the night.

Children at Play

Here are preliminary notes for a brief guest lecture I’m giving tomorrow in Professor Maya Nadarni’s course “Anthropological Perspectives on Childhood and the Family.” The topic is Children at Play.

Introduction: my larger research project

- fantastic-media objects, includes model kits, collectible statues, wargaming figurines, replica props: unreal things with material form

- these objects are an integral part of how fantastic transmedia franchises gain purchase culturally and commercial, as well as how they reproduce industrially

- particularly complex objects in terms of signification and value, mediation of mass and private, principles of construction, and local subcultures (both fan and professional) where they are taken up in different ways

- while these objects have been with us for decades, evolving within children’s culture, hobby cultures, gaming, media fandom, and special-effects practices, the advent of desktop fabrication (3D printing) paired with digital files portends a shift in the economies, ontologies, and regulation of fantastic-media objects

Jonathan Gray, Show Sold Separately: a counter-reading of toys and action figures

- examines Star Wars toys and action figures as examples of paratexts shaping interpretation of “main text”

- story of Lucas’s retention of licensing rights, considered risible at the time

- graphic showing that toys and action figures account for more profits than films and video games combined

- rescues “denigrated” category of licensed toys as “central to many fans’ and non-fans’ understandings of and engagements with the iconic text that is Star Wars. … Through play, the Star Wars toys allowed audiences past the barrier of spectatorship into the Star Wars universe.” (176)

- licensed toys provide opportunities “to continue the story from a film or television program [and] to provide a space in which meanings can be worked through and refined, and in which questions and ambiguities in the film or program can be answered.” (178)

- notes role of SW toys in sustaining audience interest during 1977-1983 period of original trilogy’s release

- transgenerational appeal of franchise linked to toys as transitional objects, providing a sense of familiarity in young fans’ identities

- current transmedia franchises include licensed objects as components of extended storyworlds

Case study in history: the objects of monster culture

- 1960s monster culture spoke to (mostly male and white) pre-teen and adolescent baby boomers

- mediated through Famous Monsters of Filmland (1958-), especially advertising pages from “Captain Company”

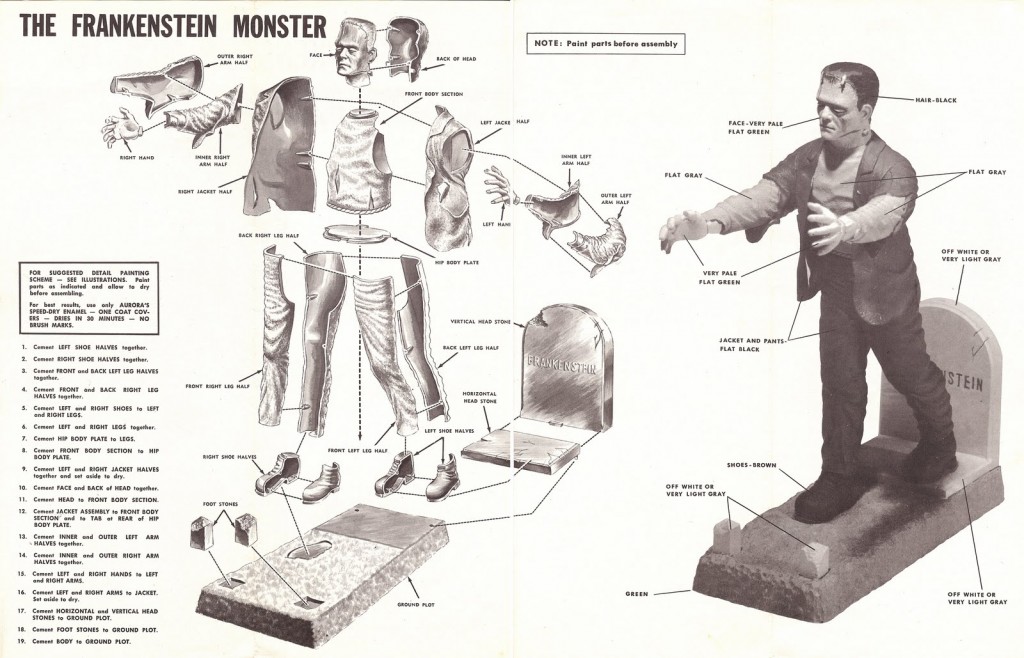

- Aurora model kits were key icons of this subculture: “plastic effigies”

- Steven M. Gelber: popularization of plastic kits represented “the ultimate victory of the assembly line,” contrasting with an earlier era of authentic creativity in which amateur crafters “sought to preserve an appreciation for hand craftsmanship in the face of industrialization.” (262-263)

- model kits provided young fans with prefab creativity, merging their own crafts with media templates; also opportunities for transformation (1964 model kit contest)

“The most intricate, beautiful map you could possibly imagine”

The first season of HBO’s Game of Thrones followed the inaugural novel of George R. R. Martin’s series so minutely that, despite its obvious excellence, I found it a bit redundant: like the early days of superhero comics in which the panel art basically just illustrated the captions, each episode had the feel of an overly faithful checklist, the impeccable casting and location work a handsome but inert frame for Martin’s baroque and sinister plotting. That’s one big reason why I’m eager to see the second season, which premieres tonight — I bogged down a hundred or so pages into book two, A Clash of Kings, and so apart from a few drips and drabs that have leaked through my spoiler filter, I’m a fresh and untrammeled audience. (Given the sheer scale of A Song of Ice and Fire, at five fat volumes and counting, the whole concept of spoilers seems beside the point, rendered irrelevant by a level of structural complexity that forces synchronic rather than diachronic understandings; it’s hard enough at any given moment to keep track of the dense web of characters, alliances, and intrigues without worrying about where they’ll all be two or three thousand pages later.)

Another reason I’m looking forward to the series’ return is its arresting title sequence, a compact masterpiece of mannered visualization that establishes mood, momentum, and setting in the span of ninety seconds:

Here is how the website Art of the Title describes the governing concept:

A fiery astrolabe orbits high above a world not our own; its massive Cardanic structure sinuously coursing around a burning center, vividly recounting an unfamiliar history through a series of heraldic tableaus emblazoned upon it. An intricate map is brought into focus, as if viewed through some colossal looking glass by an unseen custodian. Cities and towns rise from the terrain, their mechanical growth driven by the gears of politics and the cogs of war.

From the spires of King’s Landing and the godswood of Winterfell, to the frozen heights of The Wall and windy plains across the Narrow Sea, Elastic’s thunderous cartographic flight through the Seven Kingdoms offers the uninitiated a sweeping education in all things Game of Thrones.

“Elastic,” of course, refers to the special-effects house that created the sequence, and Art of the Title‘s interview with the company’s creative director, Angus Wall, is enormously enlightening. Facing the challenge of establishing the nonearthly world in which Game of Thrones takes place, Wall developed the idea of a bowl-shaped map packed with detail. In his words, “Imagine it’s in a medieval tower and monks are watching over it and it’s a living map and it’s shaped like a bowl that’s 30 feet in diameter and these guys watch over it, kind of like they would the Book of Kells or something… they’re the caretakers of this map.” Realizing the limitations of that topology, Elastic put two such bowls together to create a sphere, and placing a sun in the center, arrived at the sequence’s strange and lyrical fusion of a pre-Copernican cosmos with a Dyson Sphere.

Yet even more interesting than the sequence’s conceit of taking us inside a medieval conception of the universe — a kind of cartographic imaginary — is its crystallization of a viewpoint best described as wargaming perspective: as it swoops from one kingdom to another, the camera describes a subjectivity somewhere between a god and a military general, the eternally comparing and assessing eye of the strategist. It’s an expository visual mode whose lineage is less to classical narrative than to video-game cutscenes or the mouse-driven POV in an RTS. Its ultimate root, however, is not in digital simulation but in the tabletop wargames that preceded it — what Matthew Kirschenbaum has evocatively called “paper computers.” Kirschenbaum, a professor at the University of Maryland, blogs among other places at Zone of Influence, and his post there on the anatomy of wargames contains a passage that nicely captures the roving eye of GoT‘s titles:

Hovering over the maps, the players occupy an implicit position in relation to the game world. They enjoy a kind of omniscience that would be the envy of any historical commander, their perspectives perhaps only beginning to be equaled by today’s real-time intelligence with the aid of GPS, battlefield LANs, and 21st century command and control systems.

Earlier I mentioned the sprawling complexity of A Song of Ice and Fire, a narrative we might spatialize as unmanageably large territory — unmanageable, that is, without that other form of “paper computers,” maps, histories, concordances, indices, and family trees that bring order to Martin’s endlessly elaborated diegesis. Their obvious digital counterpart would be something like this wiki, and it’s interesting to note (as does this New Yorker profile) that the author’s contentious, codependent relationship with his fan base is often battled out in such internet forums, where creative ownership of a textual property exists in tension with custodial privilege. Perhaps all maps are, in the words of Kurt Squire and Henry Jenkins, contested spaces. If so, then the tabletop maps on which wargames are fought provide an apt metaphor both for Game of Thrones‘s narrative dynamics (driven as they are by the give-and-take among established powers and would-be usurpers) and for the franchise itself, whose fortunes have increasingly become distributed among many owners and interests.

All of this comes together in the laden semiotics of the show’s opening, which beckons to us not just as viewers but as players, inviting us to engage through this “television computer” with a narrative world and user experience drawn from both old and new forms of media, mapping the past and future of entertainment.

The Grey

It’s always interesting to witness the birth of an articulation between actor and genre — the moment when Hollywood’s endlessly spinning tumblers click into place with a tight and seemingly inevitable fit, fusing star and vehicle into a single, satisfying commercial package. For Liam Neeson, that grave and manly icon, the slot machine hit its combinatorial jackpot with 2008’s Taken, a thriller whose narrative economy was as ruthlessly single-minded as its protagonist; Neeson played a former CIA agent whose mission to rescue his kidnapped daughter lent the bloody body count a moral justification, like a perfectly-balanced throwing knife. Next came Unknown, less successful in leaping its logical gaps, but centered nonetheless by Neeson’s morose, careworn toughness.

The Grey gives us Neeson as yet another hardened but sensitive man, another action hero whose uncompromising competence in the face of disaster is saved from implausible superhumanity by virtue of the fact that he seems so reluctant to be going through it all; you sense that Neeson’s characters really wish they were in another kind of movie. It makes him just right for something like The Grey, in which a plane full of grizzled and boastful oil-drilling workers crashes in remote Alaskan territory, on what turns out to be the hunting and nesting grounds of a community of wolves. None of these guys wants to be there, especially after a crash scene so stroboscopically wrenching and whiplashy that it made my wife leave the room. Shortly after Neeson’s character makes his way to the smoking debris and discovers a handful of survivors, there is an exquisite scene in which he coaches a terminally-wounded man through the final seconds of his life. “You’re going to die,” Neeson gently and compassionately growls, as around him the other tough guys weep and turn away.

Nothing else that happens in the story quite matches that moment, and since the rest of the film is essentially one long death scene, I found myself wishing that someone like Neeson could help put the movie out of its misery. Not that the action of being hunted by wolves isn’t gripping — but as the team’s numbers wear down and it becomes clearer that no one is going to survive this thing, the tone becomes so meditative that I found myself numbing out, as though frostbitten. I’ve written before about annihilation narratives, and I continue to respond to the mordant pleasures of their zero-sum games, which appeal, I suspect, to the same part of me that likes washing every dish in the kitchen and then hosing the sink clean while the garbage disposal whirrs. (Scott Smith’s book The Ruins is perhaps my favorite recent instance of the tale from which no one escapes.) The Grey‘s slow trudge to its concluding frames induced a trance more than a chill, but the experience stayed with me for days afterward.

Sharing — or stealing? — Trek

In a neat coincidence, yesterday’s New York Times featured two articles that intersect around the concerns of internet piracy and intellectual property rights on the one hand, and struggles between fan creators and “official” owners of a transmedia franchise on the other. On the Opinions page, Rutgers professor Stuart P. Green’s essay “When Stealing Isn’t Stealing” examines the Justice Department’s case against the file-sharing site Megaupload and the larger definitions of property and theft on which the government’s case is based. Green traces the evolution of a legal philosophy in which goods are understood in singular terms as something you can own or have taken away from you; as he puts it, “for Caveman Bob to ‘steal’ from Caveman Joe meant that Bob had taken something of value from Joe — say, his favorite club — and that Joe, crucially, no longer had it. Everyone recognized, at least intuitively, that theft constituted what can loosely be defined as a zero-sum game: what Bob gained, Joe lost.”

It’s flattering to have my neanderthal namesake mentioned as the earliest of criminals, and not entirely inappropriate, as I myself, a child of the personal-computer revolution, grew up with a much more elastic and (self-)forgiving model of appropriation, one based on the easy and theoretically limitless sharing of data. As Green observes, Caveman Bob’s descendants operate on radically different terrain. “If Cyber Bob illegally downloads Digital Joe’s song from the Internet, it’s crucial to recognize that, in most cases, Joe hasn’t lost anything.” This is because modern media are intangible things, like electricity, so that “What Bob took, Joe, in some sense, still had.”

Green’s point about the intuitive moral frameworks in which we evaluate the fairness of a law (and, by implication, decide whether or not it should apply to us) accurately captures my generation’s feeling, back in the days of vinyl LPs and audiocassettes, that it was no big deal to make a mix tape and share it with friends. For that geeky subset of us who then flocked to the first personal computers — TRS-80s, Apple IIs, Commodore 64s and the like — it was easy to extend that empathic force field to excuse the rampant copying and swapping of five-and-a-quarter inch floppy disks at local gatherings of the AAPC (Ann Arbor Pirate’s Club). And while many of us undoubtedly grew up into the sort of upstanding citizens who pay for every byte they consume, I remain to this day in thrall to that first exciting rush of infinite availability promised by the computer and explosively realized by the Web. While I’m aware that pirating content does take money out of its creators’ pockets (a point Green is careful to acknowledge), that knowledge, itself watered down by the scalar conceit of micropayments, doesn’t cause me to lose sleep over pirating content the way that, say, shoplifting or even running a stop sign would. The law is a personal as well as a public thing.

The other story in yesterday’s Times, though, activates the debate over shared versus protected content on an unexpected (and similarly public/personal) front: Star Trek. Thomas Vinciguerra’s Arts story “A ‘Trek’ Script is Grounded in Cyberspace” describes the injunction brought by CBS/Paramount to stop the production of an episode of Star Trek New Voyages: Phase II, an awkwardly-named but loonily inspired fan collective that has, since 2003, produced seven hours of content that extend the 1966-1969 show. Set not just in the universe of the original series but its specific televisual utopos, the New Voyages reproduce the sets, sound effects, music, and costumes of 60s Trek in an ongoing act of mimesis that has less to do with transformative use than with simulation: the Enterprise bridge in particular is indistinguishable from the set designed by Matt Jeffries, in part because it is based on those designs and subsequent detailing by Franz Joseph and other fan blueprinters.

I’ve watched four of the seven New Voyages, and their uncanny charm has grown with each viewing. For newcomers, the biggest distraction is the recasting of Kirk, Spock, McCoy, and other regulars by different performers whose unapologetic roughness as actors is more than outweighed by their enthusiasm and attention to broad details of gesture: it’s like watching very, very good cosplayers. And now that the official franchise has itself been successfully rebooted, the sole remaining indexical connection to production history embodied by Shatner et al has been sundered. Everybody into the pool, er, transporter room!

I suspect it is the latter point — the sudden opening of a frontier that had seemed so final, encouraging every fan with a camera and an internet connection to partake in their own version of what Roddenberry pitched as a “wagon train to the stars” — that led CBS to put the kibosh on the New Voyages production of Norman Spinrad’s “He Walked Among Us,” a script written in the wake of Spinrad’s great Trek tale “The Doomsday Machine” but never filmed due to internal disputes between Roddenberry and Gene Coon about how best to rewrite it. (The whole story, along with other unrealized Trek scripts, makes for fascinating reading at Memory Alpha.) Although Spinrad was enthusiastic about the New Voyages undertaking and even planned to direct the episode, CBS, according to the Times story, decided to exert its right to hold onto the material, perhaps to publish it or mount it as some sort of online content themselves.

All of which brings us back to the question of Caveman Bob, Caveman Joe, and their cyber/digital counterparts. Corporate policing of fan production is nothing new, although Trek‘s owners have always encouraged a more permeable membrane between official and unofficial contributors than does, say, Lucasfilm. But the seriousness of purpose evidenced by the New Voyages, along with the fan base it has itself amassed, have elevated it from the half-light of the fannish imaginary — a playspace simultaneously authorized and ignored by the powers that be, like the kid-distraction zones at a McDonalds — to something more formidable, if not in its profit potential, then in its ability to deliver a Trek experience more authentic than any new corporate “monetization.” By operationalizing Spinrad’s hitherto forgotten teleplay, New Voyages reminds us of the immense generative possibilities that reside within Trek‘s forty-five years of mitochondrial DNA, waiting to be realized by anyone with the requisite resources and passion. And that’s genuinely threatening to a corporation who formerly relied on economies of scale to ensure that only they could produce new Trek at anything like the level of mass appeal.

But in proceeding as if this were the case, Green might suggest, CBS adheres to an obsolete logic of property and theft, one that insists on the uniqueness and unreproducibility of any given instantiation of Trek. They have not yet embraced the idea that, in the boundless ramifications of a healthy transmedia franchise, there is only ever “moreness”; versions do not cancel each other out, but drive new debates about canonicity and comparisons of value, fueling the discursive games that constitute the texture of an engaged and appreciative fandom. The New Voyages take nothing away from official Trek, because subtraction is an impossibility in the viral marketplace of new media. The sooner CBS realizes this, the better.

Materializing Monsters

About a year ago, I began to experiment with using this blog as a space for sketching out research projects and writing rough drafts. One of my first efforts in this direction was an essay on Famous Monsters of Filmland and Aurora model kits, which grew out of a panel I attended at the 2010 SCMS conference in Los Angeles. The panel’s organizer, Matt Yockey, was generous enough to invite me on board a themed issue he was putting together looking at FM and its editor, Forrest J Ackerman; the rudiments of the resulting essay can be found in this series of posts.

Revised and expanded, this material formed the basis of a faculty lecture I gave at Swarthmore in January, entitled “Materializing Monsters: Fan Objects and Fantastic Media.” While the talk and associated essay stand on their own, I plan to turn them into a chapter in my next book project, Object Practices: The Material Life of Media Fictions, which looks at the role of material artifacts in the production and circulation of fantastic media. (My other blog posts on this subject can be found here.)

Here’s a link to a news feature on my talk, including audio of the lecture and the PowerPoint slides that accompanied it. I invite you to check it out and comment!

Jason Mittell’s Complex TV

Passing along this word from my friend Jason Mittell, Associate Professor of American Studies and Film and Media Culture at Middlebury College, whose exciting new publication project is now available for open access and “peer-to-peer review.” He is inviting feedback on the pre-published chapters of Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling at http://mediacommons.futureofthebook.org/mcpress/complextelevision/. He shares this outline of the plan:

The book’s introduction and first chapter are posted now (as of Saturday evening, in conjunction with an SCMS workshop on digital publishing I Skyped in for from Germany). I plan on posting chapters every week or two over the next few months, serializing the release to allow time for people to read and comment (and me to finish writing). I hope that momentum will build and the conversation will flourish through this process, but this is obviously an experiment. I hope you can stop in and read the work in progress and offer feedback, and also help spread the word to others who might be interested in the topic. I would also love to hear any feedback about this unorthodox mode of publication and review.

Jason blogs at Just TV.

Spared by the gorgon’s gaze

Well, it finally happened: a friend showed me his new iPad, and I lived to tell the tale.

As I indicated in this post a few weeks ago, Apple’s recent refresh of its game-changing tablet computer struck me as something less than overwhelming — an incremental step rather than a quantum leap. Though I haven’t changed my position, I should clarify that I remain a committed iPad user and Apple enthusiast; I don’t expect miracles at every product announcement, any more than I expect every word out of my own mouth (or post on this blog) to be immortal wisdom. It’s OK for the company to tread water for a while, especially in the wake of losing Steve Jobs.

I’ve been reading Walter Isaacson’s biography of Jobs, flipping through that white slab of a book (obviously styled as a kind of print analog of an iPod) to my favorite chapters of Jobs’s history: his garage collaboration with Steve Wozniak in the mid-70s on the first Apple computer, in its cheeky wooden case; shepherding the first Macintosh to market in the early 1980s; his series of home runs twenty years later, helping to develop first iTunes and then the iPod as part of a rethinking of the personal computer as a “digital hub” for local ecosystems of smart, small, simple devices for capturing and playing back media.

It’s a modern mythology, with Jobs as an information-age Odysseus, somehow always seeing further than the people around him, taking us with him on his journey from one island of insight and inspiration to another. His death threatens to leave Apple rudderless, and the gently-revised iPad seems to me an understandable response to the fear of drifting off course. Too dramatic a correction at this point might well strand the company or distract it into losing its way entirely, and for a business so predicated on its confident mapping of the future — its navigation of nextness — that outcome is unthinkable.

The flipside, of course, is stagnation through staying the course, death by a thousand cautious shortcuts. Apple’s solution to the dilemma is symptomatized in the new iPad’s Retina display, the highest-resolution screen ever created for a mobile device. It’s hard not to intepret this almost ridiculously advanced visualization surface as a metaphor for the company’s (and our own) neurotic desire to “see” its way forward, boosting pixels and GPU cycles in an effort to scry, on a more abstract level, the ineffable quality that Steve Jobs brought to just about everything he did, summarized in that tired yet resilient word vision. We stroke the oracular glass in hopes of resolving our own future.

As in Greek tragedy, of course, such prophetic magic rarely comes without costs. The new iPad’s demanding optics send fiery currents surging through its runic circuitry, raising the device’s heat to levels that some find uncomfortable, though as Daedalus learned, sometimes you have to fly close to the sun. Hungry for power, the iPad takes a long time to charge, and doesn’t always come clean about its appetites, but who is to say if this is a bug or a feature? Not us mere mortals.

What I most worried about was looking upon the iPad’s Retina display and being forever ruined — turned to stone by the gorgon’s gaze. It happened before with the introduction of DVD, which made videocassette imagery look like bad porn; with Blu-Ray, which gave DVDs the sad glamour of fading starlets in soft-focus closeups; with HDTV, which in its dialectical coining of “standard def” (how condescendingly dismissive that phrase, the video equivalent of “she’s got a great personality”) jerrymandered my hundreds of channels into a good side and bad side of town. I was afraid that one glimpse of the new iPad would make the old iPad look sick.

But it didn’t, and for that I count myself lucky: spared for at least one more year, one more cycle of improvements. But already I can feel the pressure building, the groundwork being laid. As one by one my apps signal that they need updating to raise themselves to the level of the enhanced display’s capabilities, I imagine that I myself will one day awaken with a small circular push notification emblazoned on my forehead: ready to download an upgraded I.

Easing back into Mad Men

I am a fan of Mad Men, which puts me in a tiny minority consisting of just about everyone I know, and most of those I don’t. Perhaps it’s a holdover from my recent post on 4chan’s reaction to The Hunger Games, but I can’t shake the sense that it’s getting harder to find points of obsession in the pop-culture-scape that haven’t already been thoroughly picked over. Credit AMC, a channel that has branded itself as a reliable producer of hit shows that play like cult favorites. I suspect that my desire to hold onto the illusion that I and I alone understand the greatness of Mad Men is the reason I saved its season-five premiere a full 24 hours, sneaking upstairs to watch it in the darkness of our bedroom, the iPad’s glowing screen held inches from my eyes, the grown-up equivalent of reading under the covers with a flashlight. Let me be alone with my stories.

Somewhat hardening the hard-core of my fanboy credibility is the fact I’ve followed the show religiously since it first aired in 2007; it jumped out at me immediately as a parable of male terror, a horror story dressed in impeccable business suits. That basic anxiety has stayed with the show, though it’s only one of its many pleasures. One aspect of the series that I once believed important, the 1960s setting presented in such alien terms as to turn the past into science fiction, turns out not to be so crucial, if the failure of broadcast-network analogs Pan Am and The Playboy Club are any indication.

As for the premiere, I enjoyed it well enough, but not nearly as much as I will enjoy the rest of the season. It always takes me a while to get back into Mad Men’s vibe, with the first episodes seeming stiff and obvious, even shallow, only later deepening into the profoundly entertaining, darkly funny, and ultimately heartbreaking drama I recognize the show to be. The slow thaw reminds me of how I react to seeing Shakespeare on stage or screen: it takes twenty minutes for the rarefied language to come into focus as something other than ostentation. Mad Men too initially distances by seeming a parody of itself, but I suspect that the time it takes for my eyes and ears to adapt to this hermetically-sealed bubble universe has more to do with its precise evocation of a juncture in history when surfaces were all we had — when the culture industry, metonymized in Madison Avenue, found its brilliant stride as a generator of sizzle rather than a deliverer of steak.

Coming home

Sharing one of my exceedingly rare cigarettes with a friend at this weekend’s SCMS conference in Boston, I joked about writing an avant-garde academic text in the form of a giant palindrome: it would be a perfectly cogent argument up to the halfway point, then reverse itself and proceed backwards, until, on the last page, it ended on the same word with which it had started.

Now that my wife, son, and I are back in our house, I see that the act of travel, of being away and coming back, is a lot like that giant palindrome. All of the preparations we so carefully make before depature — packing the suitcase, loading the dishwasher, turning off the lights — reverse themselves on our arrival home, and the first small acts with which I began (always, for some reason, the zipping-up of toothbrush and razor in my toiletries bag) are the last to be performed at the other end of the experience, shuffling disordered cards back into the familiar and dog-eared deck of our everyday life. For me, there is nothing quite like the pleasure and relief of settling back in at home.

All of this has an added resonance and poignancy, because today marks one year since another act of coming home. On March 25, 2011, my wife and I lost a pregnancy at 23 weeks, after medical scans that showed profound defects in the fetus and left us with little hope for a healthy birth or normal life for the child if it survived. “Fetus,” “child,” “it”; all inadequate but protectively distancing approximations for the boy we named Arlo, delivered as the sun rose outside the windows of our room at the hospital. That room continued to brighten and warm thoughout the morning as we sat with our son, saying hello and goodbye to this tiny pound-and-a-quarter person whose motionless face, after all our weeks of fear and dread, turned out to be not so scary after all: a gentle little visage, like a thoughtful gnome’s, with eyes that never opened.

There was a certain undeniable grace to that morning, a gift of release, but by nightfall much of the spell had worn off, and by the time we got home, the first real waves of pain had started to throb through the cushion of our shock. K’s mother was here to take care of us, and our dog (now deceased) here to need us in turn, and there was mail on the kitchen table waiting to be sorted, shows on the DVR to watch.

I don’t really remember how we got through the next several weeks (though I did have a moment of startled realization not too many mornings later, sitting at the kitchen table with my wife and mother in law, that the world had not in fact ended). We did the things we normally do: cooked meals, went for walks, paid bills. Early in April some robins built a nest outside our kitchen window and filled it with perfect blue eggs from which emerged a gaggle of adorably wrinkled and disgusting beasts that soon enough turned cute, sprouted feathers, opened their eyes, and flew away. In June we submitted our adoption profile. Six weeks later, we received a call from our agency. Two days after that, we found ourselves in another hospital room, meeting the newborn baby who would become our son.

We got home after that experience, too, and I guess the lesson here is that if luck is with you, you get to come home, put the pieces of your life back together, and move on. Sometimes leaving the safety zone is voluntary and sometimes it’s forced upon you, but either way it’s usually something you have to do in order to keep on growing.

Now that spring is here, robins are starting to show up in the trees and on our lawn. Irrational as it is, I hold out hope that one or more of them are the babies we watched through our kitchen window, grown up now and coming home themselves. The nest is still there, waiting for them to settle in and unpack their suitcases.