Of Lucasfilm and LEGO, Part One

[This is the first in a series of posts on my LEGO project, described here. Be warned, I’m very much in my “word salad” phase with this project — the goal is simply 500 words of rough draft.]

Two Origin Stories

The story of LEGO’s genesis has its own faintly modular quality, parts and pieces clicking together in a way that reflects the toy’s own pleasing combination of predetermined outcome generated from open-ended possibility, the shape of the statue already extant within the uncarved block from which it will emerge. In the practiced tellings of David C. Robertson’s Brick by Brick (New York: Crown Business, 2013) and Daniel Lipkowitz’s The LEGO Book (London: DK, 2009), first came the humble workshop of Ole Kirk Kristiansen, who set up his workshop in Billund, Denmark in 1916. (Lipkowitz 12). A family business was created in 1932 to make wooden toys (Robertson 10) but evolved to embrace the plastics manufacturing capability developed in wartime and, following the end of World War 2, became available industrially in 1947, resulting in the plasticization and mass production of children’s toys (see Rehak 2012). The LEGO “system of play” emerged in 1955 and, with the patenting of the LEGO brick, became legally legible (and defensible by copyright) in 1958. (Lipkowitz 7) This system, condensed into a list of “Ten Important Characteristics,” was defined by such attributes as “unlimited play possibilities,” “endless hours of play,” “imagination, creativity, development,” and “each new product multiplies the play value of the rest.” (Lipkowitz 11) This system would evolve over the decades that followed to become ever more adaptable to consumer needs through differentiations within the product line that addressed ever finer categories of the play base, with Kjeld Kirk Kristiasen’s “system within a system” providing “each age group of consumers with the right toys at the right time in their lives.” (Lipkowitz 11). Kristiansen, according to Lipkowitz, saw himself as “a more globally oriented leader [than his grandfather], seeking to fully exploit our brand potential for further developing and broadening our product range and business concept, based upon our product idea and brand values.” (Lipkowitz 11)

The other origin story unfolds along similar lines, from humble workshop beginnings to corporate, globe-spanning mastery. In the early 1970s, George Lucas, a graduate of the University of Southern California film school, followed up his debut features THX-1138 (1971) and American Graffiti (1973) with the space fantasy Star Wars (1977), a movie marked, in retrospect, by a similar handmade quality: the difficulty of securing funding that forced Lucas to shop his screenplay around to multiple studios, the crafting of a fictional world from the detritus of other pop-cultural artifacts, and a find-it-or-build-it ethos emblematized behind the scenes by Industrial Light and Magic, the special and visual-effects house coordinated by John Dykstra. Emerging from a comparative nowhere in the founding moments of the new Hollywood blockbuster, Star Wars was explosively successful, immediately generating plans for two sequels (The Empire Strikes Back in 1980, Return of the Jedi in 1983) to form the “Original Trilogy” – an appellation that, like LEGO’s origins, would come into usage only retroactively, as more and more content followed, often received skeptically as wrongheaded permutations of an authentic essence. But viewed against the background of their global reach and granular infiltration of our physical and mediated lives, the six feature films of the Original and Prequel Trilogies are but a minute core to a vast halo of materials, images, narratives, products, and practices that constitute the franchise. Star Wars, too, would grow into a “system” promising – at least in the claims of its adherents and popularizers – endless possibilities for play and expansion.

Two Projects

Two writing projects sit on my desk, and the fact that they’ve remained there untouched throughout winter break, which ends a week from Monday, means I’d better get my butt in gear. I don’t realistically expect to complete drafts before classes resume January 20, but at the very least I can get some groundwork done. And since a working principle I’m experimenting with is that visibility via this blog is one way to short circuit the cycles of neglect and perfectionistic worry within which so many of my scholarly ambitions languish, I introduce these projects to you below.

The first is a chapter for an upcoming anthology on animation in Rutgers’ Behind the Silver Screen series. In these collections, every decade gets its own chapter — now that I think of it, a layout reminiscent of another Rutgers project I participated in, the 2003 chapter in American Cinema of the 2000s — but editor Scott Curtis, in consultation with me and the other contributors, has opted to stretch that framework in divvying up the blocks of time to respect animation’s complex and interleaved history, more a set of overlapping developments in technology, style, and economic/industrial practices than a neat linear progression. Here’s the abstract for my bit:

Ubiquitous Animation (c. 1990-2010)

The 1995 release of Toy Story marked the dawn of the fully computer-generated animated feature film, but Pixar’s technological and commercial success was only one node of a wider array of digitally-inflected animation practices that flowered in the 1990s and into the first decade of the 21st century. Across a range of screens, drawing on new tools and skills, and engaging heterogeneous subcultures of creators, audiences, fans, and players, animation between 1990 and 2010 was radically reshaped by the computer’s ability to augment, automatize, and in many cases absorb traditional modes of production while putting animated content to work in new platforms, devices, and displays. Computer-generated visual effects played an increasingly central role in building the storyworlds and performers of blockbuster cinema, from Jurassic Park (1993) to the Lord of the Rings trilogy (2000-2003); videogames such as the first-person shooters (FPS) Quake and Half-Life and massively-multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPG) Everquest and World of Warcraft took graphic shape from the specialized code of their rendering “engines”; and traditional 2D and stop-motion animation began to rely on digital tools for generating backgrounds, tweening keyframes, and erasing supports in films such as Coraline (2009) and The Secret of Kells (2009).

Picking up in 1991 with the release of Disney’s Beauty and the Beast – a film blending traditional 2D animation with CG backgrounds generated by Disney and Pixar’s CAPS (Computer Animation Production System) – this chapter charts the spread of digital animation in three spheres: traditional animation, live action feature films featured computer-generated visual effects, and high-end and casual videogaming. I trace the development of tools and production workflows that facilitated digital animation’s spread, including applications such as After Effects and Flash, motion and performance capture, photogrammetry, artificial-intelligence software for animating crowds and digital “extras,” and in the world of videogames, game engines and content editors that enabled users to create their own videogame animations known as machinima. Alongside these developments, I chart the industry’s embrace of digital animation through the founding of studios such as Pixar, Blue Sky, DreamWorks, and Sony Pictures Animation. The chapter thus emphasizes not just the computer’s role in planning and producing animated imagery, but the impact of the internet and World Wide Web in creating new communities of production and fandom, as well as the growing importance of media convergence in breaking down formerly distinct barriers between television, film, gaming, comics and graphic novels, and a pervasive ecosystem of “smart” devices and interfaces for accessing and sharing content.

There’s a lot here, and as usual when looking at proposals written long before the manuscript was due, I sense that I’ve bitten off more than I can chew — or maybe the better metaphor is that of a trip to the buffet, where I loaded up my plate with more food than I can reasonably ingest. What’s that saying? “His eyes are bigger than his stomach.” I’ve always struggled with my appetites, and while wisdom tells me to be more moderate in my choices, I suppose I will always harbor some sneaky bit of pride in thinking big, whether it’s in regard to an XL pizza with double cheese, barbecue chicken, pepperoni, and anchovies (shoutout to my favorite pizza place in Chapel Hill, NC) or a menu of tasty theoretical and historical tidbits my September 2012 self decided my January 2014 would enjoy sampling.

Here’s the other project:

Lucasfilm and LEGO: The Building Blocks of Transmedial Franchises

In 1999, the Star Wars franchise became the first intellectual property to be licensed by LEGO, with kits based on both the original and prequel trilogies becoming best-sellers over the next decade and a half. During that same period, LEGO licensed additional franchise properties such as The Lord of the Rings, Batman, and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, signaling a new industrial alliance within the transmedial storytelling systems and convergent flows of fantastic blockbuster culture. This chapter uses the LEGO/Star Wars history to examine shifts in the fortunes of both companies and their product lines, emphasizing the ways in which LEGO’s modularity and near-infinite adaptability harmonized with Lucasfilm’s efforts to expand and extend the Star Wars property through its own “modularization” of production, including prequelization, the recasting of key characters, and the eventual conversion of iconic characters, settings, and vehicles into animated forms such as the Clone Wars series (2003, 2008-present) and video games set in the world of LEGO. LEGO thus emerges as both the prototype and future of transmedial franchise building, exposing underlying industrial logics of substitution and recombination of fantasy assets, and marking a negotiated succession between analog and digital media culture.

This one is for Mark J. P. Wolf’s upcoming LEGO Studies: Examining the Building Blocks of a Transmedial Phenomenon, and before you ask, I believe I came up with the “building blocks” line first. (I’m open to correction on this, of course.) The editor, on the other hand, is behind “transmedial,” which I agree is the more elegant if less standard way of referring to properties that bridge multiple media forms in creating and narrating their virtual universes (for more on which I highly recommend Mark’s magisterial Building Imaginary Worlds). My focus here is narrower and more critical, as I firmly believe that nothing very good happened to the Star Wars franchise after 1983’s Return of the Jedi, or really after 1980’s The Empire Strikes Back. (Yup, I’m one of those fans.) Still, my planned goal in reading Lucasfilm and LEGO against each other is not to suggest that the former “ruined” the latter or vice versa, but rather to think about the interesting harmonies that link their strategies — a strange-bedfellows argument.

More on these projects as they develop; they’re my primary diet for the foreseeable future.

PotD: Welcome to the Orchard

Behold the newest addition to my little grove of devices: a fifth-generation 32GB iPod Touch. Its aluminum back is a sweet matte blue, if you’re wondering, but I’ve also encased it in a silicone sleeve to protect its wafer-thin body from damage. Oh, who am I kidding: the case is there to protect me, to numb my awareness of the new toy’s ephemerality, for that’s what you get with the latest, smartest gadgets, like a warranty you have no choice but to accept: its precise fit to the niche of today’s needs means that tomorrow (which of course might be weeks, months, or we hope years away) it will be gone. Mayfly tech. But I’ll take those odds, and try not to feel ridiculous about the way my devices are multiplying into a swarm (I believe “ecosystem” is the trendier, more palatable term) whose numbers are less about the complexity of my workflow than about how pampered I have become. I still try, desperately, to iron out every crease and complication that would give me an excuse not to write; in the early 1990s that quest took the form of splurging on a Mac Classic because I liked the way it let me make folders for everything, and now, twenty years later (still beholden to that great brand-god Apple) it takes the form of an iPad 2, an iPad Mini, the new iPod Touch, and a MacBook Air, across which flow the synchronized data of notes, snippets, links, captures, and documents that collectively constitute my “research.” The Touch fills a specific and slender slot in that system, an additional node for Evernote entries and podcast playings, that I hope will make my life perfect. I learned a long time ago that such perfection is an illusory horizon, but that turned out to be only half the lesson. What I’ve figured out more recently — helped along by mayfly technology — is that you even when you know you’ll never reach perfection, you must keep plugging away at it.

Making Mine Marvel

Reading Sean Howe’s Marvel Comics: The Untold Story (New York: Harper Perennial, 2013) I am learning all sorts of things. Or rather, some things I am learning and some things I am relearning, as Marvel’s publications are woven into my life as intimately as are Star Trek and Star Wars: other franchises of the fantastic whose fecundity — the sheer volume of media they’ve spawned over the years — mean that at any given stage of my development they have been present in some form. Our biographies overlap; even when I wasn’t actively reading or watching them, they served at least as a backdrop. I would rather forget that The Phantom Menace or Enterprise happened, but I know precisely where I was in my life when they did.

Star Wars, of course, dates back to 1977, which means my first eleven years were unmarked by George Lucas’s galvanic territorialization of the pop-culture imaginary. Trek, on the other hand, went on the air in 1966, the same year I was born. Save for a three-month gap between my birthday in June and the series premiere in September, Kirk, Spock and the universe(s) they inhabit have been as fundamental and eternal as my own parents. Marvel predates both of them, coming into existence in 1961 as the descendent of Timely and Atlas. This makes it about as old as James Bond (at least in his movie incarnation) and slightly older than Doctor Who, arriving via TARDIS, er, TV in 1963.

My chronological preamble is in part an attempt to explain why so much of Howe’s book feels familiar even as it keeps surprising me by crystallizing things about Marvel I kind of already knew, because Marvel itself — avatarizalized in editor/writer Stan Lee — was such an omnipresent engine of discourse, a flow of interested language not just through dialogue bubbles and panel captions but the nondiegetic artists’ credits and editorial inserts (“See Tales of Suspense #53! — Ed.”) as well as paratextual spaces like the Bullpen Bulletins and Stan’s Soapbox. Marvel in the 1960s, its first decade of stardom, was very, very good not just at putting out comic books but at inventing itself as a place and even a kind of person — a corporate character — spending time with whom was always the unspoken emotional framework supporting my issue-by-issue excursions into the subworlds of Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four, and Dr. Strange.

Credit Howe, then, with taking all of Marvel’s familiar faces, fictional and otherwise, and casting each in its own subtly new light: Stan Lee as a liberal, workaholic jack-in-the-box in his 40s rather than the wrinkled avuncular cameo-fixture of recent Marvel movies; Jack Kirby as a father of four, turning out pages at breakneck speed at home in his basement studio with a black-and-white TV for company; Steve Ditko as — and this genuinely took me by surprise — a follower of Ayn Rand who increasingly infused his signature title, The Amazing Spider-Man, with Objectivist philosophy.

It’s also interesting to see Marvel’s transmedial tendencies already present in embryo as Lee, Kirby, and Ditko shared their superhero assets across books: Howe writes, “Everything was absorbed into the snowballing Marvel Universe, which expanded to become the most intricate fictional narrative in the history of the world: thousands upon thousands of interlocking characters and episodes. For generations of readers, Marvel was the great mythology of the modern world.” (Loc 125 — reading it on my Kindle app). Of course, as with any mythology of sufficient popular mass, it becomes impossible to read history as anything but a teleologically overdetermined origin story, so perhaps Howe overstates the case. Still, it’s hard to resist the lure of reading marketing decisions as prescient acts of worldbuilding: “It was canny cross-promotion, sure, but more important, it had narrative effects that would become a Marvel Comics touchstone: the idea that these characters shared a world, that the actions of each had repercussions on the others, and that each comic was merely a thread of one Marvel-wide mega-story.” (Loc 769)

I like too the way Untold Story paints comic-book fandom in the 1960s as a movement of adults, or at least teenagers and college students, rather than the children so often caricatured as typical comic readers; Howe notes July 27, 1964 as the date of “the first comic convention” at which “a group of fans rented out a meeting hall near Union Square and invited writers, artists, and collectors (and one dealer) of old comic books to meet.” (Loc 876) The company’s self-created fan club, the Merry Marvel Marching Society or M.M.M.S., was in Howe’s words

an immediate smash; chapters opened at Princeton, Oxford, and Cambridge. … The mania wasn’t confined to the mail, either — teenage fans started calling the office, wanting to have long telephone conversations with Fabulous Flo Steinberg, the pretty young lady who’d answered their mail so kindly and whose lovely picture they’d seen in the comics. Before long, they were showing up in the dimly lit hallways of 625 Madison, wanting to meet Stan and Jack and Steve and Flo and the others. (Loc 920)

A forcefully engaged and exploratory fandom, then, already making its media pilgrimages to the hallowed sites of production, which Lee had so skillfully established in the fannish imaginary as coextensive with, or at least intersecting, the fictional overlay of Manhattan through which Spider-Man swung and the Fantastic Four piloted their Fantasticar. In this way the book’s first several chapters offhandedly map the genesis of contemporary, serialized, franchised worldbuilding and the emergent modern fandoms that were both those worlds’ matrix and their ideal sustaining receivers.

Howe is attentive to these resonances without overstating them: Lee, Kirby and others are allowed to be superheroes (flawed and bickering in true Marvel fashion) while still retaining their earthbound reality. And through his book, so far, I am reexperiencing my own past in heightened, colorful terms, remembering how the media to which I was exposed when young mutated me, gamma-radiation-like, into the man I am now.

PotD: Standup Guy

Inspired slash horrified by reports such as this, I’m experimenting with a new system of standing while working — in fact, I’m going the whole hog, marching in place around my office and doing a weird constrained form of jumping jacks that I believe I learned from Dr. Smith on Lost in Space. It’s doing wonders for my back, which last semester was sometimes so crimped after a day of hunching at my desk I couldn’t stand up straight; pain multiplied by the occasional task of shoveling snow off our driveway, and there ware days I was basically confined to couch or bed. Anyway, here’s my makeshift workstation on campus, perched on a filing cabinet at just about the right height to keep my spine in line. Close-eyed observers might note the bottle of soy sauce with which I spike my spartan tuna-and-lettuce salads; the biography of Marvel Comics I’m currently reading (and the related blog-post-in-progress on my MacBook Air); the grad-school diplomas I haven’t gotten around to hanging even though I earned my Ph.D in 2006 and am now a tenured associate professor; the hat that will keep my poor ears warm when I leave the office in a few minutes; and, tinily, my wedding ring, which I tend to take off before doing any substantial typing.

CFP: Making the Marvel Universe

Making the Marvel Universe: Transmedia and the Marvel Comics Brand

Editor: Matt Yockey

What became known as the Marvel Universe in effect began with the publication in 1961of Fantastic Four no. 1, a comic book that redefined the superhero genre with its exploits of a bickering superhero team. In little more than a year a company that had gone through numerous name changes since it began as Timely Publications in 1939 not only settled on a new one – Marvel Comics – but also embraced a new identity as an iconoclastic “House of Ideas,” overseen by the jocular and familiar editorial presence of Stan Lee and defined by the unique creative vision of artists such as Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko. Previously in the shadow of DC Comics, the dominant publisher in the industry, by the end of the 1960s Marvel had completely rewritten the rules of what superhero comic books could be. Not only did the “Marvel Bullpen” produce a new wave of unusually complex superheroes – including Spider-Man, the Incredible Hulk, Doctor Strange, the X-Men, and Iron Man – but they redefined the ways in which comic books were read. The Marvel Universe was constituted by an overall continuity between titles to an unprecedented degree; cross-over stories evolved into a complex meta-text that incorporated every superhero title the company published. With Lee as the face of the company, Marvel became not only the leading publisher of superhero comic books but (after a few false starts) eventually optioned its properties into successful blockbuster films, beginning in 2000 with X-Men. This led to Marvel establishing its own film production company that is currently producing a collection of movies that are the film equivalent of the Marvel Universe. With comic books no longer the mainstream commodity they once were, Marvel has effectively exploited the transmedia potential of their properties and remains more relevant and more lucrative a business concern than ever before.

This anthology will examine the various ways by which Marvel in effect has become Marvel. Essays can focus on a single character, comic book title, film, television series, writer, artist, director, actor, franchise, or era. They can also take a more global perspective on a particular way in which the Marvel Universe and/or the Marvel brand function. Various methodologies are welcomed. Potential topics include but are not limited to:

- Authorship

- Creator’s rights

- Adaptation

- Convergence culture and world-making

- Canon formation

- Rebooting and retconning

- “Bad” textsand their place in the Marvel Universe

- Marvel as “The House of Ideas,” the “Marvel Bullpen,” the “Marvel Method,” and production culture

- Company-created fan clubs (Merry Marvel Marching Society and FOOM) and/or Marvel fandom in general

- Stan Lee’s persona

- Marvel’s claims to “relevance” and the political and social significance of its work

- Corporate identity: the creation of brand identity and values; the role of the corporation in relation to fans

- Globalization: the marketing of Marvel and the universalizing of brand values

- Web-comics and the evolution of reading habits

- Nostalgia

- Marketing strategies and aesthetics

- The DC/Marvel binary

- Disney’s purchase of Marvel and the shifting identity of the company

Interested authors should submit a proposal of approximately 400-600 words. Each proposal should clearly state 1) the research question and/or theoretical goals of the essay, 2) the essay’s relationship to the anthology’s core issues, and 3) a potential bibliography. Please also include a brief CV. Accepted essays should be approximately 6,000-7,000 words.

Deadline for proposals: October 15, 2013

Please send proposals to: matt.yockey@utoledo.edu

Publication timetable:

- October 15, 2013 – Deadline for Proposals

- November 15, 2013 – Notification of Acceptance Decisions

- March 15, 2014 – Chapter Drafts Due

- June 15, 2014 – Chapter Revisions Due

- July 31, 2014 – Final Revisions Due

Acceptance will be contingent on the ability of contributors to meet these deadlines and deliver high-quality work.

Tilt-Shifting Pacific Rim

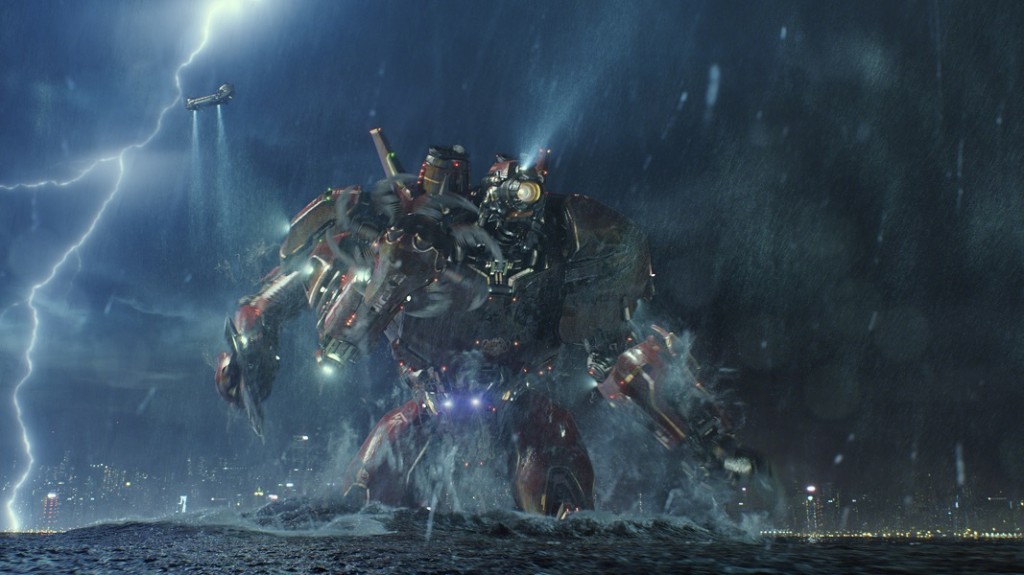

Two-thirds of the way through Pacific Rim — just after an epic battle in, around, and ultimately over Hong Kong that’s one of the best-choreographed setpieces of cinematic SF mayhem I have ever witnessed — I took advantage of a lull in the storytelling to run to the restroom. In the air-conditioned chill of the multiplex the lobby with its concession counters and videogames seemed weirdly cramped and claustrophobic, a doll’s-house version of itself I’d entered after accidentally stumbling into the path of a shink-ray, and I realized for the first time that Guillermo del Toro’s movie had done a phenomenological number on me, retuning my senses to the scale of the very, very big and rendering the world outside the theater, by contrast, quaintly toylike.

I suspect that much of PR’s power, not to mention its puppy-dog, puppy-dumb charm, lies in just this scalar play. The cinematography has a way of making you crane your gaze upwards even in shots that don’t feature those lumbering, looming mechas and kaiju. The movie recalls the pleasures of playing with LEGO, model kits, action figures, even plain old Matchbox Cars, taking pieces of the real (or made-up) world and shrinking them down to something you can hold in your hand — and, just as importantly, look up at. As the father of a two-year-old, I often find myself laying on the floor, my eyes situated inches off the carpet and so near the plastic dump trucks, excavators, and fire engines in my son’s fleet that I have to take my glasses off to properly focus on them. At this proximity, toys regain some of their large-scale referent’s visual impact without ever quite giving up their smallness: the effect is a superimposition of slightly dissonant realities, or in the words of my friend Randy (with whom I saw Pacific Rim) a “sized” version of the uncanny valley.

This scalar unheimlich is clearly on the culture’s mind lately, literalized — iconized? — in tilt-shift photography, which takes full-sized scenes and optically transforms them into images that look like dioramas or models. A subset of the larger (no pun intended) practice of miniature faking, tilt-shift updates Walter Benjamin’s concept of the optical unconscious for the networked antheap of contemporary digital and social media, in which nothing remains unconscious (or unspoken or unexplored) for long but instead swims to prominence through an endless churn of collective creation, commentary, and sharing. Within the ramifying viralities of Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, Reddit, and 4chan, in which memes boil reality into existence like so much quantum foam, the fusion of lens-perception and human vision — what the formalist Soviet pioneers called the kino-eye — becomes just another Instagram filter:

The giant robots fighting giant monsters in Pacific Rim, of course, are toyetic in a more traditional sense: where tilt-shift turns the world into a miniature, PR uses miniatures to make a world, because that is what cinematic special effects do. The story’s flimsy romance, between Raleigh Beckett (Charlie Hunnam) and Mako Mori (Rinko Kikuchi) makes more sense when viewed as a symptomatic expression of the national and generic tropes the movie is attempting to marry: the mind-meldly “drift” at the production level fuses traditions of Japanese rubber-monster movies like Gojiru and anime like Neon Genesis Evangelion with a visual-effects infrastructure which, while a global enterprise, draws its guiding spirit (the human essence inside its mechanical body, if you will) from Industrial Light and Magic and the decades of American fantasy and SF filmmaking that led to our current era of brobdingnagian blockbusters.

Pacific Rim succeeds handsomely in channeling those historical and generic traces, paying homage to the late great Ray Harryhausen along the way, but evidently its mission of magnifying 50’s-era monster movies to 21st-century technospectacle was an indulgence of giantizing impulses unsuited to U.S. audiences at least; in its opening weekend, PR was trounced by Grown Ups 2 and Despicable Me 2, comedies offering membership in a franchise where PR could offer only membership in a family. The dismay of fans, who rightly recognize Pacific Rim as among the best of the summer season and likely deserving of a place in the pantheon of revered SF films with long ancillary afterlives, should remind us of other scalar disjunctions in play: for all their power and reach (see: the just-concluded San Diego Comic Con), fans remain a subculture, their beloved visions, no matter how expansive, dwarfed by the relentless output of a mainstream-oriented culture industry.

Starting the Last of Us

The remarkable opening sequence of The Last of Us was ruined for me — at my request, I hasten to add — and as much as it might be in keeping with the game’s ethos of cowing and disempowering its players, I don’t want to visit the same epistemological violence upon readers without warning. So proceed no further if you wish to remain unspoiled!

After a long sojourn in retro tidepools of emulation (via MAME and Nestopia) and the immediate, delimited pleasures of casual gaming (where usual suspects like Bejeweled and Temple Run share playtime with private-feeling discoveries like Alien Zone and Nimble Quest) I’m returning to modern videogaming with a PlayStation 3 — itself on the verge of obsolescence, I suppose, thanks to the imminent PS4. My motivations for acquiring both The Last of Us and hardware to run it on can be traced to an hour or so of gaming at a friend’s place, where, as my two companions watched and kibbitzed, I walked, crouched, and ran TLOU’s protagonist-avatar Joel through a couple of early “encounters” whose purpose seemed to be to teach me the futility of fighting, shooting, or doing anything really besides sneaking around or flat-out running away from danger.

I find TLOU’s strategy of undermining any sense of potency or agency to be one of its most intriguing traits, but I will wait to talk more about that in a future post. For now I simply want to note the clever, evil way in which the game gets its hooks in you. You begin the game playing as Sarah, Joel’s twelve-year-old daughter, and the initial sequence involves piloting her around a darkened house in search of her father. It’s suitably creepy, with Sarah calling out “Dad?” in increasingly panicked tones as, outside the game, you adapt yourself to the basics of movement, camera placement, and manipulating objects in the environment.

The latter is a now-standard method of starting a game in crypto-tutorial mode — apparently sometime within the last ten years instruction manuals ceased to exist. Controllers have become standardized according to their brands, but each videogame deploys its button-and-joystick layout slightly differently, and acclimatizing the player to this scheme in a way that feels natural is every game’s first design challenge, a kind of ludic bootstrapping.

When Joel arrives home in the middle of the night and spirits Sarah off in a pickup truck, TLOU enters another mode, the expository tour, in this case a bone-rattling run through a world in the process of collapsing: police cars screeching by with sirens blaring (and lenses flaring), houses burning, townspeople rioting. Rushed from one apocalyptic setpiece to another, it’s a bit like Disney’s “Small World” ride filtered through Dante’s Inferno. By this point, avatarial focus has been handed off to Joel, but you barely notice it; he’s carrying Sarah in his arms as he runs, so it feels like he, she, and you have merged into a single unit of desperate, hounded motion.

And when it appears that the three of you have finally reached safety, a soldier appears, opens fire, and kills Sarah. Cut to black and the title card: THE LAST OF US.

It’s a great opening, harrowing and emasculating, and by breaking a couple of the basic expectations of storytelling (killing a child) and of gaming (killing an avatar we have grown used to inhabiting), it decenters and disorients the player, readying him or her for what is to come by demonstrating precisely how unready we really are.

It put me in mind of Psycho, which similarly kills off its ostensible protagonist at the end of its first act — though in the 1960 film Marion Crane has had a moral defect established that makes her, in retrospect at least, deserving of punishment in Hitchcock’s sadistic scopic regime. Sarah, by contrast, is an innocent, and as much a cipher as emblems of purity always are. Starting the game with her death is a manipulative but effective gut-punch that can be read both positively and negatively. It was enough to make me take the leap and reengage with contemporary gaming — well, it and a few other things. But more on that later.

Fun with your new head

The title of this post is borrowed from a book of short stories by Thomas M. Disch, and it’s doubly appropriate in that an act of borrowing arguably lies at the heart of the latest 3D-printing novelty to catch my eye: a British company called Firebox will take pictures of your own head, turn them into a 3D-printed noggin, and stick it on a superhero body. As readers of this blog probably know, I’m intrigued by desktop-fabrication technologies less for their ability to coin unique inventions (the “rapid prototyping” side of their operations) and more for the interesting wrinkles they introduce to the production and circulation of licensed and branded objects — especially fantasy objects, which are referentially unreal but tightly circumscribed by designs associated with particular franchises. Superhero bodies are among the purest examples of such artifacts, offering immediately recognizable physiologies and costumes such as Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman; all of which are among the bodies onto which you can slap your replacement head.

The title of this post is borrowed from a book of short stories by Thomas M. Disch, and it’s doubly appropriate in that an act of borrowing arguably lies at the heart of the latest 3D-printing novelty to catch my eye: a British company called Firebox will take pictures of your own head, turn them into a 3D-printed noggin, and stick it on a superhero body. As readers of this blog probably know, I’m intrigued by desktop-fabrication technologies less for their ability to coin unique inventions (the “rapid prototyping” side of their operations) and more for the interesting wrinkles they introduce to the production and circulation of licensed and branded objects — especially fantasy objects, which are referentially unreal but tightly circumscribed by designs associated with particular franchises. Superhero bodies are among the purest examples of such artifacts, offering immediately recognizable physiologies and costumes such as Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman; all of which are among the bodies onto which you can slap your replacement head.

Aside from literalizing the dual-identity structure that has always offered us mild-mannered Clark Kents a means of climbing into Kryptonian god-suits, what I love about this is its neat encapsulation of the deeper ideological function of the 3D-printed fantasy object, giving people the opportunity not just to locate themselves amid an array of mass produced yet personally significant forms (as in, for example, a collection of action figures) but to materialize themselves within and as part of that array, through plastic avatars that also serve as a kind of cyborg expression of commercialized subjectivity. That Firebox (and, presumably, license-holder DC Comics) currently offer a controlled version of that hybridity is only, I think, a symptom of our prerevolutionary moment, poised at the brink of an explosion of such transmutations and transubstantiations, legal and illegal alike, though which the virtual and material objects of fantastic media will not just swap places but find freshly bizarre combinatorial forms.