This post from the New York Times Bits blog is one of the first I’ve seen to address the problems — and opportunities — likely to be created by personal-fabrication technology, aka 3D printing, when it encounters copyright law designed for an earlier era. As Nick Bilton points out, having a box on your desktop that manufactures solid objects from data files opens the door to the physical reproduction not just of objects you have designed yourself, but objects that already exist:

Not only will it change the nature of manufacturing, but it will further challenge our concept of ownership and copyright. Suppose you covet a lovely new mug at a friend’s house. So you snap a few pictures of it. Software renders those photos into designs that you use to print copies of the mug on your home 3-D printer. Did you break the law by doing this? You might think so, but surprisingly, you didn’t.

Bilton goes on to explain that while copyright law protects one kind of object — the aesthetic — from being replicated without permission of the owner, another class of item — the utilitarian — is fair game. “If an object is purely aesthetic it will be protected by copyright, but if the object does something, it is not the kind of thing that can be protected,” Bilton quotes attorney Michael Weinberg as saying. The logic goes something like this: if you could conceivably have made your own version of the mug in, say, a pottery class, it wouldn’t be illegal; so employing a hardware intermediary to accomplish the same goal is similarly allowed.

The apparently tidy distinction between the artful and the useful suggests that there is more at stake here than simply case law and precedent, the glacial patching of traditional legislation to apply to nontraditional processes and products. (Lawrence Lessig’s remix culture might here be understood as replication culture.) In addition to foregrounding the question of how we name and assign value to the things around us, personal fabrication foregrounds new kinds of objects that fall somewhere between the pretty and the practical, neither toy nor tool but something in between, with branded identities and iconographic affordances that make them the powerful focus of manufacturing and collecting, as well as performative and procedural, activity both at the subcultural and “supercultural” level.

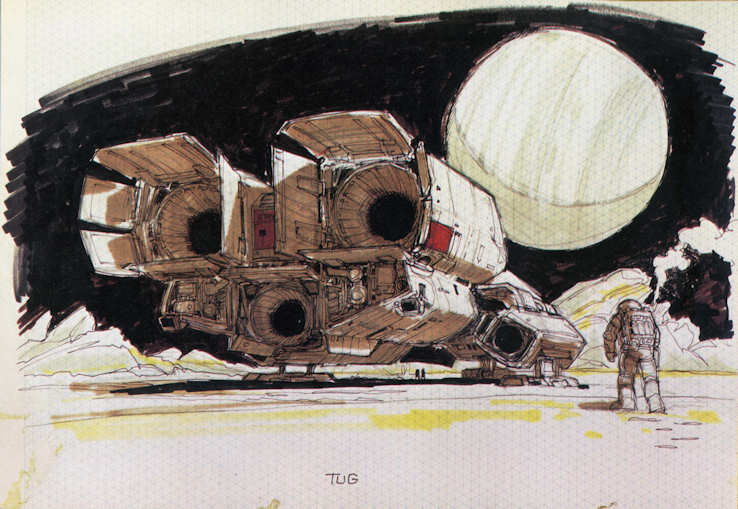

I’ve been interested in 3D printing since 2007, when I came across Neil Gershenfeld’s book Fab: The Coming Revolution on Your Desktop. (Gershenfeld is the director of MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms and perhaps the key proselytizer of what the Times has labeled the Industrial Revolution 2.0.) For me, as a theorist and fan of popular culture and fantastic media franchises in particular, the profound shakeup promised by 3D printing is less about designing new kinds of widgets or copying existing ones than about the way that fantasy-media objects and the practices around them will be reshaped. Spaceship models, superhero collectible busts, even fantasy-wargaming miniatures — the colorful statuary on display in any comic-book store, materialized forms of what otherwise exists only on paper — will inevitably find their place within the personal-fabrication movement. Most of these objects are licensed, of course, and provided by artists under contract with companies like Sideshow Collectibles and McFarlane Toys. But to adapt the question that Bilton poses, what will happen when I can snap several photos of a friend’s Green Lantern maquette or Warhammer 40K mini, stitch them together on my iPhone (you can bet there’ll be an app for that), send the resulting shape file to my 3D printer, and produce my own instance?

Surely then the intellectual-property hammer will come down — under current codes, there’s no way to justify a Captain Kirk figurine or the Doctor’s Sonic Screwdriver as a practical rather than an aesthetic object — and we’ll witness not the elimination of unlicensed fantasy-media objects, but their migration to the anarchic wilds of piracy, newsgroups, and torrents, just as current “flat” media content like television, movies, and ebooks circulate free for the taking. To date I’ve found little discussion of the role of such objects and their probable audiences, i.e. tech-savvy scofflaws, in the 3D printing literature, which focuses instead on the rapid-prototyping function of these emerging technologies: testing out new inventions or generating workaday things like flashlights and doorknobs. But it’s precisely this dividing line, between the things we use and the things we enjoy because they connect us to vast transmedia entertainment systems, that will dictate 3D printing’s future as the commercial and cultural juggernaut I suspect it will be.