This review is dedicated to my friends David Surman and Will Brooker.

Part One: We Have Never Been Digital

***

If Avatar was in fact the “gamechanger” its prosyletizers claimed, then it’s fitting that the first film to surpass it is itself about games, gamers, and gaming. Arriving in theaters nearly a year to the day after Cameron’s florid epic, Tron: Legacy delivers on the promise of an expanded blockbuster cinema while paradoxically returning it to its origins.

Those origins, of course, date back to 1982, when the first Tron — brainchild of Steven Lisberger, who more and more appears to be the Harper Lee of pop SF, responsible for a single inspired act of creation whose continued cultural resonance probably doomed any hope of a career — showed us what CGI was really about. I refer not to the actual computer-generated content in that film, whose 96-minute running time contains only 15-20 minutes of CG animation (the majority of the footage was achieved through live-action plates shot in high contrast, heavily rotoscoped, and backlit to insert glowing circuit paths into the environment and costumes), but instead to the discursive aura of the digital frontier it emits: another sexy, if equally illusory, glow. Tron was the first narrative feature film to serve up “the digital” as a governing design aesthetic as well as a marketing gimmick. Sold as high-tech entertainment event, audiences accepted Lisberger’s folly as precisely that: a time capsule from the future, coming attraction as main event. Tron taught us, in short, to mistake a hodgepodge of experiment and tradition as a more sweeping change in cinematic ontology, a spell we remain under to this day.

But the state of the art has always been a makeshift pact between industry and audience, a happy trance of “I know, but even so …” For all that it hinges on a powerful impression of newness, the self-applied declaration of vanguard status is, ironically, old hat in filmmaking, especially when it comes to the periodic eruptions of epic spectacle that punctuate cinema’s more-of-the-same equilibrium. The mutations of style and technology that mark film’s evolutionary leaps are impossible to miss, given how insistently they are promoted: go to YouTube and look at any given Cecil B. DeMille trailer if you don’t believe me. “Like nothing you’ve ever seen!” may be an irresistible hook (at least to advertisers), but it’s rarely true, if only because trailers, commercials, and other advance paratexts ensure we’ve looked at, or at least heard about, the breakthrough long before we purchase our tickets.

In the case of past breakthroughs, the situation becomes even more vexed. What do you do with a film like Tron, which certainly was cutting-edge at the time of its release, but which, over the intervening twenty-eight years, has taken on an altogether different veneer? I was 16 when I first saw it, and have frequently shown its most famous setpiece — the lightcycle chase — in courses I teach on animation and videogames. As a teenager, I found the film dreadfully inert and obvious, and rewatching it to prepare for Tron: Legacy, I braced myself for a similarly graceless experience. What I found instead was that a magical transformation had occurred. Sure, the storytelling was as clumsy as before, with exposition that somehow managed to be both overwritten and underexplained, and performances that were probably half-decent before an editor diced them them into novocained amateurism. The visuals, however, had aged into something rather beautiful.

Not the CG scenes — I’d looked at those often enough to stay in touch with their primitive retrogame charm. I’m referring to the live-action scenes, or rather, the suturing of live action and animation that stands in for computer space whenever the camera moves close enough to resolve human features. In these shots, the faces of Flynn (Jeff Bridges), Tron (Bruce Boxleitner), Sark (David Warner), and the film’s other digital denizens are ovals of flickering black-and-white grain, their moving lips and darting eyes hauntingly human amid the neon cartoonage.

Peering through their windows of backlit animation, Tron‘s closeups resemble those in Dreyer’s Passion of Joan of Arc — inspiration for early film theorist Béla Balázs’s lyrical musings on “The Face of Man” — but are closer in spirit to the winking magicians of George Méliès’s trick films, embedded in their phantasmagoria of painted backdrops, double exposures, and superimpositions. Like Lisberger, who would intercut shots of human-scaled action with tanks, lightcycles, and staple-shaped “Recognizers,” Méliès alternated his stagebound performers with vistas of pure artifice, such as animated artwork of trains leaving their tracks to shoot into space. Although Tom Gunning argues convincingly that the early cinema of attractions operated by a distinctive logic in which audiences sought not the closed verisimilar storyworlds of classical Hollywood but the heightened, knowing presentation of magical illusions, narrative frameworks are the sauce that makes the taste of spectacle come alive. Our most successful special effects have always been the ones that — in an act of bistable perception — do double duty as story.

In 1982, the buzzed-about newcomer in our fantasy neighborhoods was CGI, and at least one film that year — Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan — featured a couple of minutes of computer animation that worked precisely because they were set off from the rest of the movie, as special documentary interlude. Other genre entries in that banner year for SF, like John Carpenter’s remake of The Thing and Steven Spielberg’s one-two punch of E.T. and Poltergeist (the latter as producer and crypto-director), were content to push the limits of traditional effects methods: matte paintings, creature animatronics, gross-out makeup, even a touch of stop-motion animation. Blade Runner‘s effects were so masterfully smoggy that we didn’t know what to make of them — or of the movie, for that matter — but we seemed to agree that they too were old school, no matter how many microprocessors may have played their own crypto-role in the production.

“Old school,” however, is another deceptively relative term, and back then we still thought of special effects as dividing neatly into categories of the practical/profilmic (which really took place in front of the camera) and optical/postproduction (which were inserted later through various forms of manipulation). That all special effects — and all cinematic “truths” — are at heart manipulation was largely ignored; even further from consciousness was the notion that soon we would redefine every “predigital” effect, optical or otherwise, as possessing an indexical authenticity that digital effects, well, don’t. (When, in 1998, George Lucas replaced some of the special-effects shots in his original Star Wars trilogy with CG do-overs, the outrage of many fans suggested that even the “fakest” products of 70’s-era filmmaking had become, like the Velveteen Rabbit, cherished realities over time.)

Tron was our first real inkling that a “new school” was around the corner — a school whose presence and implications became more visible with every much-publicized advance in digital imaging. Ron Cobb’s pristine spaceships in The Last Starfighter (1984); the stained-glass knight in Young Sherlock Holmes (1985); the watery pseudopod in The Abyss (1989); each in its own way raised the bar, until one day — somewhere around the time of Independence Day (1996), according to Michele Pierson — it simply stopped mattering whether a given special effect was digital or analog. In the same way that slang catches on, everything overnight became “CGI.” That newcomer to the neighborhood, the one who had people peering nervously through their drapes at the moving truck, had moved in and changed the suburb completely. Special-effects cinema now operated under a technological form of the one-drop rule: all it took was a dab of CGI to turn the whole thing into a “digital effects movie.” (Certain film scholars regularly use this term to refer to both Titanic [1997] and The Matrix [1999], neither of which employs more than a handful of digitally-assisted shots — many of these involving intricate handoffs from practical miniatures or composited live-action elements.)

Inscribed in each frame of Tron is the idea, if not the actual presence, of the digital; it was the first full-length rehearsal of a special-effects story we’ve been telling ourselves ever since. Viewed today, what stands out about the first film is what an antique and human artifact — an analog artifact — it truly is. The arrival of Tron: Legacy, simultaneously a sequel, update, and reimagining of the original, gives us a chance to engage again with that long-ago state of the art; to appreciate the treadmill evolution of blockbuster cinema, so devoted to change yet so fixed in its aims; and to experience a fresh and vastly more potent vision of what’s around the corner. The unique lure (and trap) of our sophisticated cinematic engines is that they never quite turn that corner, never do more than freeze for an instant, in the guise of its realization, a fantasy of film’s future. In this sense — to rephrase Bruno Latour — we have never been digital.

Part Two: 2,415 Times Smarter

***

In getting a hold on what Tron: Legacy (hereafter T:L) both is and isn’t, I find myself thinking about a line from its predecessor. Ed Dillinger (David Warner), figurative and literal avatar of the evil corporation Encom, sits in his office — all silver slabs and glass surfaces overlooking the city’s nighttime gridglow, in the cleverest and most sustained of the thematic conceits that run throughout both films: the paralleling, to the point of indistinguishability, of our “real” architectural spaces and the electronic world inside the computer. (Two years ahead of Neuromancer and a full decade before Snow Crash, Tron invented cyberspace.)

Typing on a desk-sized touchscreen keyboard that neatly predates the iPad, Dillinger confers with the Master Control Program or MCP, a growling monitorial application devoted to locking down misbehavior in the electronic world as it extends its own reach ever outward. (The notion of fascist algorithm, policing internal imperfection while growing like a malignancy, is remapped in T:L onto CLU — another once-humble program omnivorously metastasized.) MCP complains that its plans to infiltrate the Pentagon and General Motors will be endangered by the presence of a new and independent security watchdog program, Tron. “This is what I get for using humans,” grumbles MCP, which in terms of human psychology we might well rename OCD with a touch of NCP. “Now wait a minute,” Dillinger counters, “I wrote you.” MCP replies coldly, “I’ve gotten 2,415 times smarter since then.”

The notion that software — synecdoche for the larger bugaboo of technology “itself” — could become smarter on its own, exceeding human intelligence and transcending the petty imperatives of organic morality, is of course the battery that powers any number of science-fiction doomsday scenarios. Over the years, fictionalizations of the emergent cybernetic predator have evolved from single mainframe computers (Colossus: The Forbin Project [1970], WarGames [1983]) to networks and metal monsters (Skynet and its time-traveling assassins in the Terminator franchise) to graphic simulations that run on our own neural wetware, seducing us through our senses (the Matrix series [1999-2003]). The electronic world established in Tron mixes elements of all three stages, adding an element of alternative storybook reality a la Oz, Neverland … or Disneyworld.

Out here in the real world, however, what runs beneath these visions of mechanical apocalypse is something closer to the Technological Singularity warned of by Ray Kurzweil and Vernor Vinge, as our movie-making machinery — in particular, the special-effects industry — approaches a point where its powers of simulation merge with its custom-designed, mass-produced dreams and nightmares. That is to say: our technologies of visualization may incubate the very futures we fear, so intimately tied to the futures we desire that it’s impossible to sort one from the other, much less to dictate which outcome we will eventually achieve.

In terms of its graphical sophistication as well as the extended forms of cultural and economic control that have come to constitute a well-engineered blockbuster, Tron: Legacy is at least 2,415 times “smarter” than its 1982 parent, and whatever else we may think of it — whatever interpretive tricks we use to reduce it to and contain it as “just a movie” — it should not escape our attention that the kind of human/machine fusion, not to mention the theme of runaway AI, at play in its narrative are surface manifestations of much more vast and far-reaching transformations: a deep structure of technological evolution whose implications only start with the idea that celluloid art has been taken over by digital spectacle.

The lightning rod for much of the anxiety over the replacement of one medium by another, the myth of film’s imminent extinction, is the synthespian or photorealistic virtual actor, which, following the logic of the preceding paragraphs, is one of Tron: Legacy‘s chief selling points. Its star, Jeff Bridges, plays two roles — the first as Flynn, onetime hotshot hacker, and the second as CLU, his creation and nemesis in the electronic world. Doppelgangers originally, Flynn has aged while CLU remains unchanged, the spitting image of Flynn/Bridges circa 1982.

Except that this image doesn’t really “spit.” It stares, simmers, and smirks; occasionally shouts; knocks things off tables; and does some mean acrobatic stunts. But CLU’s fascinating weirdness is just as evident in stillness as in motion (see the top of this post), for it’s clearly not Jeff Bridges we’re looking at, but a creepy near-miss. Let’s pause for a moment on this question: why a miss at all? Why couldn’t the filmmakers have conjured up a closer approximation, erasing the line between actor and digital double? Nearly ten years after Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within, it seems that CGI should have come farther. After all, the makers of T:L weren’t bound by the aesthetic obstructions that Robert Zemeckis imposed on his recent films, a string of CG waxworks (The Polar Express [2004], Beowulf [2007], A Christmas Carol [2009], and soon — shudder — a Yellow Submarine remake) in which the inescapable wrongness of the motion-captured performances are evidently a conscious embrace of stylization rather than a failed attempt at organic verisimilitude. And if CLU were really intended to convince us, he could have been achieved through the traditional retinue of doubling effects: split-frame mattes, body doubles in clever shot-reverse-shot arrangements, or the combination of these with motion-control cinematography as in the masterful composites of Back to the Future 2, which, made in 1989, is only seven years older than the first Tron.

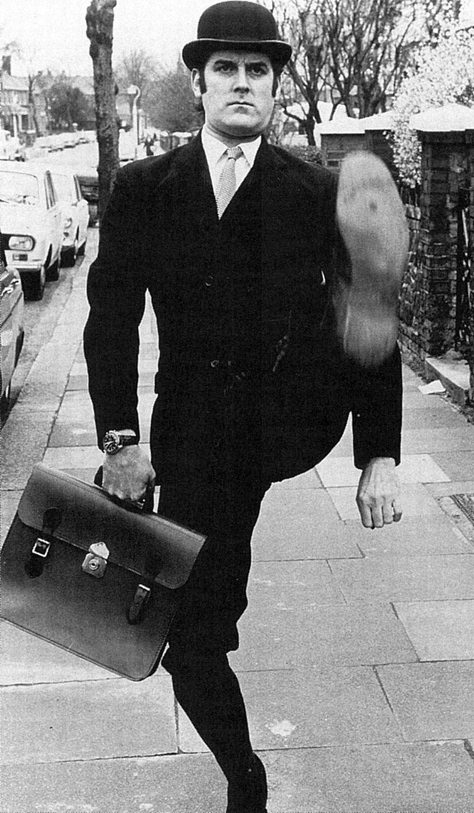

The answer to the apparent conundrum is this: CLU is supposed to look that way; we are supposed to notice the difference, because the effect wouldn’t be special if we didn’t. The thesis of Dan North’s excellent book Performing Illusions is that no special effect is ever perfect — we can always spot the joins, and the excitement of effects lies in their ceaseless toying with our faculties of suspicion and detection, the interpretation of high-tech dreams. Updating the argument for synthespian performances like CLU’s, we might profitably dispose of the notion that the Uncanny Valley is something to be crossed. Instead, smart special effects set up residence smack-dab in the middle.

Consider by analogy the use of Botox. Is the point of such cosmetic procedures to absolutely disguise the signs of age? Or are they meant to remain forever fractionally detectable as multivalent signifiers — of privilege and wealth, of confident consumption, of caring enough about flaws in appearance to (pretend to) hide them? Here too is evidence of Tron: Legacy’s amplified intelligence, or at least its subtle cleverness: dangling before us a CLU that doesn’t quite pass the visual Turing Test, it simultaneously sells us the diegetically crucial idea of a computer program in the shape of human (which, in fact, it is) and in its apparent failure lulls us into overconfident susceptibility to the film’s larger tapestry of tricks. 2,415 times smarter indeed!

Part Three: The Sea of Simulation

***

Doubles, of course, have always abounded in the works that constitute the Tron franchise. In the first film, both protagonist (Flynn/Tron) and antagonist (Sark/MCP) exist as pairs, and are duplicated yet again in the diegetic dualism of real world/electronic world. (Interestingly, only MCP seems to lack a human manifestation — though it could be argued that Encom itself fulfills that function, since corporations are legally recognized as people.) And the hall of mirrors keeps on going. Along the axis of time, Tron and Tron: Legacy are like reflections of each other in their structural symmetry. Along the axis of media, Jeff Bridges dominates the winter movie season with performances in both T:L and True Grit, a kind of intertextual cloning. (The Dude doesn’t just abide — he multiplies.)

Amid this rapture of echoes, what matters originality? The critical disdain for Tron: Legacy seems to hinge on three accusations: its incoherent storytelling; its dependence on special effects; and the fact that it’s largely a retread of Tron ’82. I’ll deal with the first two claims below, but on the third count, T:L must surely plead “not guilty by reason of nostalgia.” The Tron ur-text is a tale about entering a world that exists alongside and within our own — indeed, that subtends and structures our reality. Less a narrative of exploration than of introspection, its metaphysics spiral inward to feed off themselves. Given these ouroboros-like dynamics, the sequel inevitably repeats the pattern laid down in the first, carrying viewers back to another embedded experience — that of encountering the first Tron — and inviting us to contrast the two, just as we enjoy comparing Flynn and CLU.

But what about those who, for reasons of age or taste, never saw the first Tron? Certainly Disney made no effort to share the original with us; their decision not to put out a Blu-Ray version, or even rerelease the handsome two-disk 20th anniversary DVD, has led to conspiratorial muttering in the blogosphere about the studio’s coverup of an outdated original, whose visual effects now read as ridiculously primitive. Perhaps this is so. But then again, Disney has fine-tuned the business of selectively withholding their archive, creating rarity and hence demand for even their flimsiest products. It wouldn’t at all surprise me if the strategy of “disappearing” Tron pre-Tron: Legacy were in fact an inspired marketing move, one aimed less at monetary profit than at building discursive capital. What, after all, do fans, cineastes, academics, and other guardians of taste enjoy more than a privileged “I’ve seen it and you haven’t” relationship to a treasured text? Comic-Con has become the modern agora, where the value of geek entertainment items is set for the masses, and carefully coordinated buzz transmutes subcultural fetish into pop-culture hit.

It’s maddeningly circular, I know, to insist that it takes an appreciation of Tron to appreciate Tron: Legacy. But maybe the apparent tautology resolves if we substitute terms of evaluation that don’t have to do with blockbuster cinema. Does it take appreciation of Ozu (or Tarkovsky or Haneke or [insert name here]) to appreciate other films by the same director? Tron: Legacy is not in any classical sense an auteurist work — I couldn’t tell you who directed it without checking IMDb — but who says the brand itself can’t function as an auteur, in the sense that a sensitive reading of it depends on familiarity with tics and tropes specific to the larger body of work? Alternatively, we might think of Tron as sub-brand of a larger industrial genre, the blockbuster, whose outward accessibility belies the increasingly bizarre contours of its experience. With its diffuse boundaries (where does a blockbuster begin and end? — surely not within the running time of a single feature-length movie) and baroque textual patterns (from the convoluted commitments of transmedia continuity to rapidfire editing and slangy shorthands of action pacing), the contemporary blockbuster possesses its own exotic aesthetic, one requiring its own protocols of interpretation, its own kind of training, to properly engage. High concept does not necessarily mean non-complex.

Certainly, watching Tron: Legacy, I realized it must look like visual-effects salad to an eye untrained in sensory overwhelm. I don’t claim to enjoy everything made this way: Speed Racer made me queasy, and Revenge of the Fallen put me into an even deeper sleep than did the first Transformers. T:L, however, is much calmer in its way, perhaps because its governing look — blue, silver, and orange neon against black — keeps the frame-cramming to a minimum. (The post-1983 George Lucas committed no greater sin than deciding to pack every square inch of screen with nattering detail.) Here the sequel’s emulation of Tron‘s graphics is an accidental boon: limited memory and storage led in the original to a reliance on black to fill in screen space, a restriction reinvented in T:L as strikingly distinctive design. Our mad blockbusters may indeed be getting harder to watch and follow. But perhaps we shouldn’t see this as proof of commercially-driven intellectual bankruptcy and inept execution, but as the emergence of a new — and in its way, wonderfully difficult and challenging — mode of popular art.

T:L works for me as a movie not because its screenplay is particularly clever or original, but because it smoothly superimposes two different orders of technological performance. The first layer, contained within the film text, is the synthesis of live action and computer animation that in its intricate layering succeeds in creating a genuinely alternate reality: action-adventure seen through the kino-eye. Avatar attempted this as well, but compared to T:L, Cameron’s fantasia strikes me as disingenuous in its simulationist strategy. The lush green jungles of Pandora and glittering blue skin of the Na’vi are the most organic of surfaces in which CGI could cloak itself: a rendering challenge to be sure, but as deceptively sentimental in its way as a Thomas Kinkade painting. Avatar is the digital performing in “greenface,” sneakily dissembling about its technological core. Tron: Legacy, by contrast, takes as its representational mission simulation itself. Its tapestry of visual effects is thematically and ontologically coterminous with the world of its narrative; it is, for us and for its characters, a sea of simulation.

Many critics have missed this point, insisting that the electronic world the film portrays should have reflected the networked environment of the modern internet. But what T:L enshrines is not cyberspace as the shared social web it has lately become, but the solipsistic arena of first-person combat as we knew it in videogames of the late 1970s. As its plotting makes clear, T:L is at heart about the arcade: an ethos of rastered pyrotechnics and three-lives-for-a-quarter. The adrenaline of its faster scenes and the trances of its slower moments (many of them cued by the silver-haired Flynn’s zen koans) perfectly capture the affective dialectics of cabinet contests like Tempest or Missile Command: at once blazing with fever and stoned on flow.

The second technological performance superimposed on Tron: Legacy is, of course, the exhibition apparatus of IMAX and 3D, inscribed in the film’s planning and execution even for those who catch the print in lesser formats. In this sense, too, T:L advances the milestone planted by Avatar, beacon of an emerging mode of megafilm engineering. It seems the case that every year will see one such standout instance of expanded blockbuster cinema — an event built in equal parts from visual effects and pop-culture archetypes, impossible to predict but plain in retrospect. I like to imagine that these exemplars will tend to appear not in the summer season but at year’s end, as part of our annual rituals of rest and renewal: the passing of the old, the welcoming of the new. Tron: Legacy manages to be about both temporal polarities, the past and the future, at once. That it weaves such a sublime pattern on the loom of razzle-dazzle science fiction is a funny and remarkable thing.

***

To those who have read to the end of this essay, it’s probably clear that I dug Tron: Legacy, but it may be less clear — in the sense of “twelve words or less” — exactly why. I confess I’m not sure myself; that’s what I’ve tried to work out by writing this. I suppose in summary I would boil it down to this: watching T:L, I felt transported in a way that’s become increasingly rare as I grow older, and the list of movies I’ve seen and re-seen grows ever longer. Once upon a time, this act of transport happened automatically, without my even trying; I stumbled into the rabbit-holes of film fantasy with the ease of … well, I’ll let Laurie Anderson have the final words.

I wanted you. And I was looking for you.

But I couldn’t find you.

I wanted you. And I was looking for you all day.

But I couldn’t find you. I couldn’t find you.You’re walking. And you don’t always realize it,

but you’re always falling.

With each step you fall forward slightly.

And then catch yourself from falling.

Over and over, you’re falling.

And then catching yourself from falling.

And this is how you can be walking and falling

at the same time.