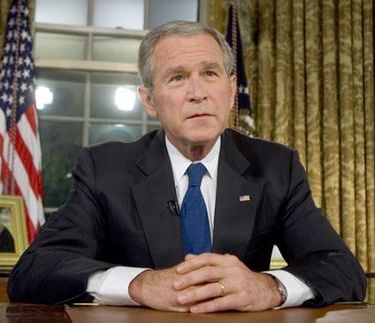

This cheerful fellow is Chuck Bartowski (Zachary Levi), the lead character on NBC’s new series Chuck. Notable not just for its privileged placement as the lead-in to Heroes on Monday nights, Chuck stands out to me as a particularly significant shift in how primetime network TV audiences are conceptualized and spoken to — or to use a fancy but endlessly useful term from Louis Althusser’s work, interpellated. Like Heroes, Chuck offers viewers a user-friendly form of complex, mildly fantastical narrative: call it science-fiction lite, albeit several shades “liter” than Heroes‘s chase-structured saga of anxious, insecure superheroes or Lost‘s island of brooding mindgamers. In fact, as I think back over the family tree from which Chuck seems to have sprouted, I detect a steady march toward the innocuous: consider the progression from Twin Peaks to The X-Files to Buffy: The Vampire Slayer to Lost and its current offspring. Dark stuff, yes, but delivered in ever more buoyantly funny and sexy packages. (Only Battlestar Galactica seems determined to honor its essentially traumatic and decentering premise.)

But maybe I’m putting Chuck in the wrong box. The show is a cross between Alias and Ed, with a little sprinkle of Moonlighting and a generous glaze of rapid, self-conscious dialogue in the style of Gilmore Girls and Grey’s Anatomy. The main character works at a big electronics chain (think The 40-Year-Old Virgin, though here the brand milieu has not even been disguised to the degree it was in that movie — Chuck is a member of the “Nerd Herd,” a smug shoutout to the corporately-manufactured tech cred of Best Buy’s Geek Squad). The conceit on which the show gambles the audience’s disbelief is that Chuck has acquired a vast trove of classified “intel” through exposure to an image-filled email (think the cursed videotape of The Ring crossed with the brainwashing montage of The Parallax View) and now finds himself at the intersecting foci of several large, conspiratorial, deadly government organizations. Not a setup that necessarily oozes laughs and romance. But laughs and romance is what, in this case, we get. Like Levi’s unassuming good looks, Chuck‘s puppydog appeal seems destined to win over audiences — though handicapping shows this early is a fool’s game.

Monday’s pilot episode efficiently established that Chuck will be aided in his navigation of the dangers ahead not just by a beautiful female secret agent (Yvonne Strahovski), but his nebbishly sidekick at “Buy More.” In case we were skeptical of Chuck’s pedigree as a leading man, that is, the scenario helpfully supplies a socially-stunted homunculus in the form of his buddy Morgan Grimes (Joshua Gomez), shifting the burden of comic relief from Chuck and thereby moving him a crucial rung up the status ladder. While Chuck responds to his sudden aquisition of epistemological ordnance with deer-in-the-headlights cluelessness, Morgan takes to the larger game right away, advising Chuck on sexual tactics and the correct way to defeat a ninja with a sureness of touch derived equally, one presumes, from excessive masturbation and too many hours playing Splinter Cell and Metal Gear Solid.

What impresses me is that Chuck not only gives us a scenario geared toward geek fetishes, but embeds within itself a passel of geeks as decoding agents and centers of action. In this regard, it’s something like a virtual-reality program running on Star Trek‘s holodeck: a choose-your-own-adventure game whose ideological lure consists of nakedly mirroring its player/viewer in the form of a central character who is not, at least at first glance, a fantasy ideal, a performative mask, a second skin. It impresses me, but also alarms me. It is a storytelling tactic that all too serendipitously echoes the larger strategies of that most expert and ephemeral of modern commodities, the TV serial, which seeks to win from us one simple thing: our ongoing commitment. Chuck acknowledges that its audience is made up of prefab fans, eager for new affiliations, no matter how machine-lathed and focus-group-tested those engines of imaginary engagement may be. (In fact, it congratulates the audience for “getting” its nested inside jokes, chief among which is the fact of their own commodification; the ideal viewer of Chuck is precisely the illegal torrenter of media that NBC hopes to convert with its downloadable content.) Plotwise, with what I’m confident will be a spiraling shell-game of reveals and cliffhangers building toward some season-ending epiphany, Chuck will surely feed the jouissance of genre-based prediction and diegetic decryption that Tim Burke has labelled “nerd hermeneutics.”

I may or may not watch Chuck, depending on my taste for my own taste for cotton candy. By comparison, Heroes, which opened its second season on Monday night, was reassuringly byzantine and willing to frustrate. Perhaps that’s the value of new TV shows, which seem so offputtingly transparent in the way they play on our pleasures — revealing to us how easily we are taken in (and taken aboard), again and again. New shows come along and retroactively establish the authenticity of their predecessors, just as Chuck, measured against next year’s new offerings, will surely ripen from empty copy to cherished original.