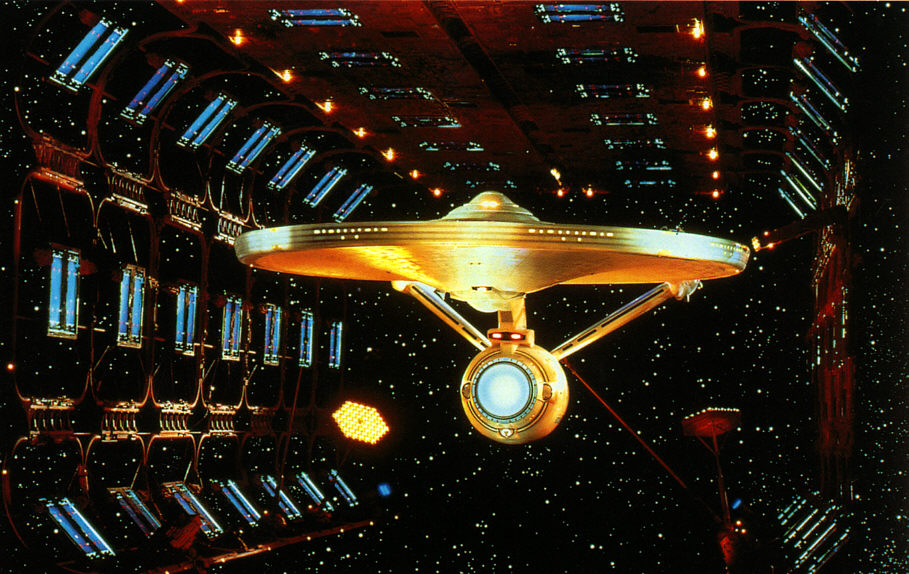

Reading Sean Howe’s Marvel Comics: The Untold Story (New York: Harper Perennial, 2013) I am learning all sorts of things. Or rather, some things I am learning and some things I am relearning, as Marvel’s publications are woven into my life as intimately as are Star Trek and Star Wars: other franchises of the fantastic whose fecundity — the sheer volume of media they’ve spawned over the years — mean that at any given stage of my development they have been present in some form. Our biographies overlap; even when I wasn’t actively reading or watching them, they served at least as a backdrop. I would rather forget that The Phantom Menace or Enterprise happened, but I know precisely where I was in my life when they did.

Star Wars, of course, dates back to 1977, which means my first eleven years were unmarked by George Lucas’s galvanic territorialization of the pop-culture imaginary. Trek, on the other hand, went on the air in 1966, the same year I was born. Save for a three-month gap between my birthday in June and the series premiere in September, Kirk, Spock and the universe(s) they inhabit have been as fundamental and eternal as my own parents. Marvel predates both of them, coming into existence in 1961 as the descendent of Timely and Atlas. This makes it about as old as James Bond (at least in his movie incarnation) and slightly older than Doctor Who, arriving via TARDIS, er, TV in 1963.

My chronological preamble is in part an attempt to explain why so much of Howe’s book feels familiar even as it keeps surprising me by crystallizing things about Marvel I kind of already knew, because Marvel itself — avatarizalized in editor/writer Stan Lee — was such an omnipresent engine of discourse, a flow of interested language not just through dialogue bubbles and panel captions but the nondiegetic artists’ credits and editorial inserts (“See Tales of Suspense #53! — Ed.”) as well as paratextual spaces like the Bullpen Bulletins and Stan’s Soapbox. Marvel in the 1960s, its first decade of stardom, was very, very good not just at putting out comic books but at inventing itself as a place and even a kind of person — a corporate character — spending time with whom was always the unspoken emotional framework supporting my issue-by-issue excursions into the subworlds of Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four, and Dr. Strange.

Credit Howe, then, with taking all of Marvel’s familiar faces, fictional and otherwise, and casting each in its own subtly new light: Stan Lee as a liberal, workaholic jack-in-the-box in his 40s rather than the wrinkled avuncular cameo-fixture of recent Marvel movies; Jack Kirby as a father of four, turning out pages at breakneck speed at home in his basement studio with a black-and-white TV for company; Steve Ditko as — and this genuinely took me by surprise — a follower of Ayn Rand who increasingly infused his signature title, The Amazing Spider-Man, with Objectivist philosophy.

It’s also interesting to see Marvel’s transmedial tendencies already present in embryo as Lee, Kirby, and Ditko shared their superhero assets across books: Howe writes, “Everything was absorbed into the snowballing Marvel Universe, which expanded to become the most intricate fictional narrative in the history of the world: thousands upon thousands of interlocking characters and episodes. For generations of readers, Marvel was the great mythology of the modern world.” (Loc 125 — reading it on my Kindle app). Of course, as with any mythology of sufficient popular mass, it becomes impossible to read history as anything but a teleologically overdetermined origin story, so perhaps Howe overstates the case. Still, it’s hard to resist the lure of reading marketing decisions as prescient acts of worldbuilding: “It was canny cross-promotion, sure, but more important, it had narrative effects that would become a Marvel Comics touchstone: the idea that these characters shared a world, that the actions of each had repercussions on the others, and that each comic was merely a thread of one Marvel-wide mega-story.” (Loc 769)

I like too the way Untold Story paints comic-book fandom in the 1960s as a movement of adults, or at least teenagers and college students, rather than the children so often caricatured as typical comic readers; Howe notes July 27, 1964 as the date of “the first comic convention” at which “a group of fans rented out a meeting hall near Union Square and invited writers, artists, and collectors (and one dealer) of old comic books to meet.” (Loc 876) The company’s self-created fan club, the Merry Marvel Marching Society or M.M.M.S., was in Howe’s words

an immediate smash; chapters opened at Princeton, Oxford, and Cambridge. … The mania wasn’t confined to the mail, either — teenage fans started calling the office, wanting to have long telephone conversations with Fabulous Flo Steinberg, the pretty young lady who’d answered their mail so kindly and whose lovely picture they’d seen in the comics. Before long, they were showing up in the dimly lit hallways of 625 Madison, wanting to meet Stan and Jack and Steve and Flo and the others. (Loc 920)

A forcefully engaged and exploratory fandom, then, already making its media pilgrimages to the hallowed sites of production, which Lee had so skillfully established in the fannish imaginary as coextensive with, or at least intersecting, the fictional overlay of Manhattan through which Spider-Man swung and the Fantastic Four piloted their Fantasticar. In this way the book’s first several chapters offhandedly map the genesis of contemporary, serialized, franchised worldbuilding and the emergent modern fandoms that were both those worlds’ matrix and their ideal sustaining receivers.

Howe is attentive to these resonances without overstating them: Lee, Kirby and others are allowed to be superheroes (flawed and bickering in true Marvel fashion) while still retaining their earthbound reality. And through his book, so far, I am reexperiencing my own past in heightened, colorful terms, remembering how the media to which I was exposed when young mutated me, gamma-radiation-like, into the man I am now.