Thanks to an incredibly generous gift certificate from some friends, my wife and I spent last weekend at a ritzy hotel in Washington, DC – where the 100-degree temperatures made us quite happy to stay inside, work out in the fitness center, order room service, and watch TV.

But the one time we had to venture outside was to visit the National Air and Space Museum, my favorite spot in Washington and, perhaps, the greatest place in the known universe. Ever since I first visited DC, at nine or ten years old, I have loved the NASM: the satellites suspended from the ceiling, the Imax theater, the giant Robert McCall mural, the silver packets of freeze-dried ice cream, and of course the full-size Skylab sitting on its end like a small cylindrical skyscraper, a constant line of people threading through its begadgeted, submarinelike innards.

I’ve been to the museum several times, so it was a shock to come face-to-face with one of its most famous artifacts, and realize that – somehow – I’d forgotten it was there. It used to hang gloriously over the entrance to some special exhibit (Spaceflight in Science Fiction, maybe?), which has now been replaced by a room devoted to the role of computers in aeronautical design and engineering. As for the marvelous object, it has moved to the lower floor of the gift shop, where it sits toward the back in its own plexiglass box, big enough to hold a Hummer…

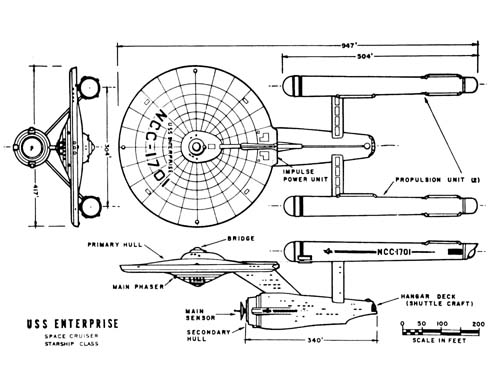

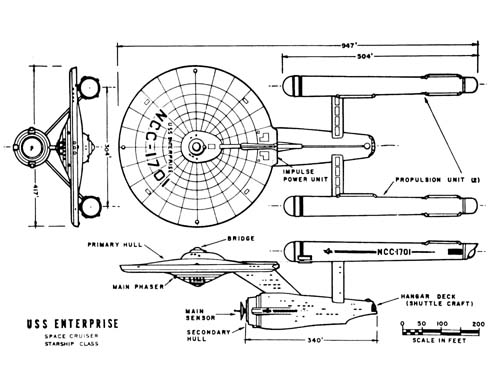

This is the original miniature of the U.S.S. Enterprise, used for optical effects shots in the first series of Star Trek (1966-1969). It’s been part of the Smithsonian collection since 1974, and has undergone several modifications in that time, including a new “mosaic” paint job to simulate square hull plating. (This concept, introduced with the starship’s redesign for Star Trek: The Motion Picture [Robert Wise, 1979], has since become standard for Trek’s vessels, reflected in the numerous sequels and series that constitute the franchise.)

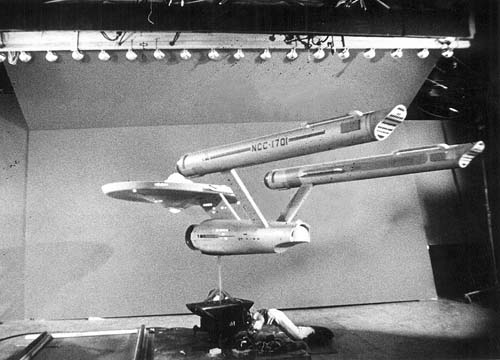

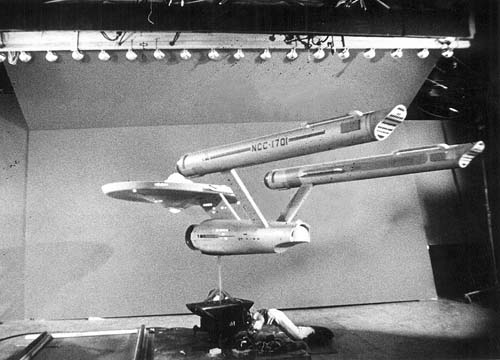

After gazing reverently at the Enterprise for a while, I dragged my wife over to see it. I explained to her – feeling somewhat like a goofball – that this was not just a replica or facsimile, but the actual shooting model that went before the cameras of the Howard Anderson effects company, to which Desilu Studios farmed out its optical work. (Actually, the miniature made the rounds of several FX houses, including Film Effects of Hollywood, the Westheimer Company, and Van Der Veer Photo Effects – Trek demanding a particularly high number of expensive and time-consuming optical effects.) Eleven feet long and weighing 200 pounds, the miniature is made of poplar wood, vacuformed plastic, and sheet metal. It was one of three Enterprises used in shooting (the others included a small balsa-wood version that appeared in the “swish” flybys of the title sequence, and a three-foot version used to show the ship in the far distance). It was designed by Walter “Matt” Jefferies in consultation with series creator Gene Roddenberry, and build by Richard C. Datin, Jr.

The miniature undeniably has a sad aspect to it now. Consigned to what is essentially the museum basement, it sits by a shelf of books about Star Trek and Star Wars like an aging carny hawking its wares. Once lit from within by a complex electrical system of lights and relays, it is now shadowed and gloomy, its sepulchral air made more poignant by the racks of day-glow flags, posters, and coffee mugs that surround it. (In this, the back corner of the gift shop, the air-and-space motif gives way to a randomly-themed grab bag of DC memorabilia: Washington Monument t-shirts, Abraham Lincoln yo-yos.)

Yet despite or perhaps because of the diorama of motley neglect in which I encountered it, the Enterprise miniature possesses an historical solidity, a gravity classifying it as the best kind of museum exhibit: one that belongs simultaneously to past and present, functioning as a material bridge between one moment in time and another. For as I circled the plexiglass case, snapping pictures with my digital camera, I realized that the real magic was not in seeing the Enterprise with my own eyes. It was, instead, in the act of capturing its image — of being physically present at one node of a visual apparatus, framing the model in my viewfinder and recording the light rays reflecting off its surface. In doing so, I fleetingly occupied the position of the original camera operators at Howard Anderson and Van Der Veer in Hollywood in the late 1960s, whose daily job it was to line up and shoot this structure of wood and plastic.

This, I suggest, is the real experience of the Enterprise. As a viewer growing up, watching the show on TV, I saw the starship only in its final composited form – as an “actual” vessel in space – experiencing a play-along immediacy that is the basic perceptual displacement necessary to the operation of television, movies, and videogames (we can only believe what we are seeing if we disbelieve in the fact of its having-been-made). Photographing the model at the National Air and Space Museum on Saturday, I experienced a flash of disbelief’s opposite, what I can only call mediacy, bringing layers of technology and labor – of historical material practice – back into the picture. It was like going to work and going to church at the same time, like punching a timeclock that is also a reliquary holding the bones of a saint. It was great; I’ll never forget it.