This summer will see the release of Ridley Scott’s Prometheus, a project weighted by considerable expectations given its connection to the thirty-year-old Alien franchise. The particulars of that connection have been kept vague by producers — witness the tortuous finessing of the film’s Wikipedia page:

Conceived as a prequel to Scott’s 1979 science fiction horror film Alien, rewrites of Spaihts’ script by [Damon] Lindelof developed a separate story that precedes the events of Alien, but which is not directly connected to the films in the Alien franchise. According to Scott, though the film shares “strands of Alien’s DNA, so to speak,” and takes place in the same universe, Prometheus will explore its own mythology and ideas.

This kind of strategic ambiguity is a hallmark of the viral marketplace, which replaces the saturation bombing of traditional advertising with the planting of clues and fomenting of mysteries. It’s a fan dance in two senses, scattering meaningful fragments before an audience whose passionate interest and desire to interact are a given. Its logic is that of nonlinear equations and unpredictably large outcomes from small causes, harnessing the butterfly effect to build buzz.

Any lingering doubt about the franchise pedigree of Prometheus, however, should be put to rest by this piece of viral marketing, a simulated TED talk from the year 2023.

The link here is, of course, the identity of the speaker: Peter Weyland is one of the founders of Weyland-Yutani, the evil corporation behind most of the important events in the Alien-Predator universe. “The Company,” as it’s referred to in the 1979 film that launched the franchise, is in part a developer and supplier of armaments, and across the films, comics, and novels of the series, the Company pursues the bioweapon represented by the toothy xenomorph with an implacable willingness to sacrifice human lives: capitalism reconfigured as carnivorous, all-consuming force.

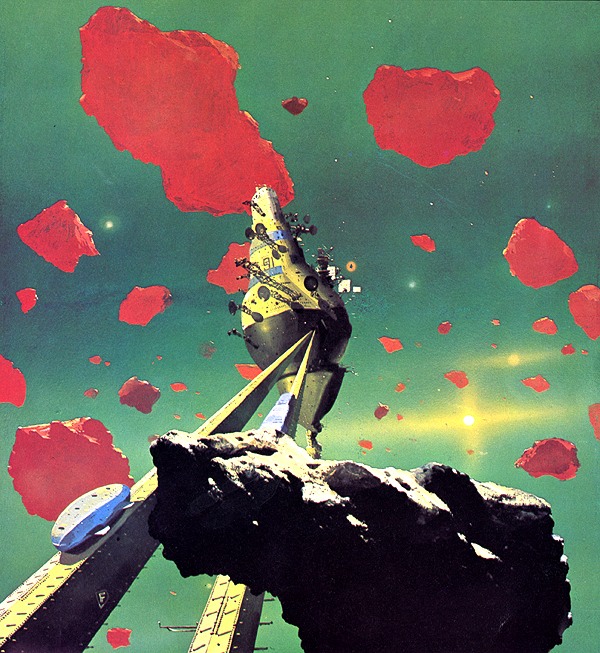

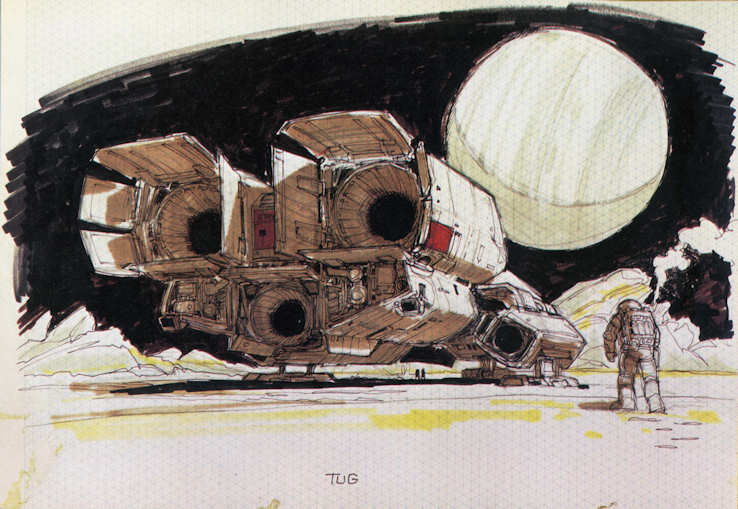

The real-world origins of Weyland-Yutani are quite specific: the name and logo were invented by illustrator Ron Cobb as part of the preproduction and concept art for Alien. Cobb designed many of the symbols and insignia that decorate the uniforms and props of the Nostromo, small but distinctive details that lend the movie’s lived-in future a unity of invented brands. One icon in particular, a set of wings modeled on an Egyptian “sun disk,” was associated with Weyland-Yutani, a name that Cobb threw together as a combination of in-joke and future history:

Science fiction films offer golden opportunities to throw in little scraps of information that suggest enormous changes in the world. There’s a certain potency in those kinds of remarks. Weylan Yutani for instance is almost a joke, but not quite. I wanted to imply that poor old England is back on its feet and has united with the Japanese, who have taken over the building of spaceships the same way they have now with cars and supertankers. In coming up with a strange company name I thought of British Leyland and Toyota, but we couldn’t use “Leyland-Toyota” in the film. Changing one letter gave me “Weylan,” and “Yutani” was a Japanese neighbor of mine.

A version of this logo and the current version of the company name (which adds a “d” to “Weylan”) ends the simulated TED talk, demonstrating another chaos dynamic that shapes the fortunes of fantastic-media franchises: minute details of production design can blossom, with the passage of the years, into giant nodes of continuity. These nodes unify not just the separate installments of a series of films, but their transmedia and paratextual extensions: the fantasy TED talk “belongs” to the Alien universe thanks to its shared use of Cobb’s design assets. Instances like this make a convincing case that 1970s production design in science fiction film laid the groundwork for the extensive transmedia fantasy worlds of today.

As for Peter Weyland’s talk, which was directed by Ridley Scott’s son and scripted by Damon Lindelof (co-creator of another complex serial narrative, LOST), the bridging of science fiction and science fact here manifests as a collusion between brands, one fictional and one “real” — but how real is TED, anyway? I mean this not as a slam, but as acknowledgment that TED often operates in what Phil Rosen has termed “the rhetoric of the forecast,” speculating about futures that lie just around the corner. In this way, perhaps the 2023 TED talk is an example of what Jean Baudrillard called a “deterrence machine,” using its own explicit fictiveness to reinforce the sense of reality around TED, much like Disneyland in relation to Los Angeles:

Disneyland is there to conceal the fact that it is the “real” country, all of “real” America, which is Disneyland (just as prisons are there to conceal the fact that it is the social in its entirety, in its banal omnipresence, which is carceral). Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real, when in fact all of Los Angeles and the America surrounding it are no longer real, but of the order of the hyperreal and of simulation. It is no longer a question of a false representation of reality (ideology), but of concealing the fact that the real is no longer real, and thus of saving the reality principle.

One wonders what Baudrillard would have made of the contemporary transmediascape, with its vast and dispersed fictional worlds superintending a swarm of texts and products, the nostalgic archives of its past, the hyped adumbrations of its present. Certainly our entertainment industries are becoming ever more sophisticated in the rigor and reach of their fantasy construction: a fan dance with the future, and a process in which observant audiences eagerly assist.