As my attention shifts to one of the major goals of the summer — drafting a proposal for my book on special and visual effects — I’ve started to augment my movie-a-day habit with some classic FX titles. These are films I’ve seen before, in some cases many times, but which need revisiting. Seeing them now can be a corrective shock, revealing my memory for the sloppy generalizing mechanism it is. Impressions of movies watched in childhood blend together, in the adult mind, like ingredients of a stew, a delicious melange that is nevertheless a kind of monotaste: a tidy averaging of visual and narrative pleasures that, with a fresh viewing, shatter back into discrete components. The movie again becomes a complex terrain rather than a distant map, a succession of contrasting images rather than a single iconic poster still, a cascade of rediscovered characters, tableaux, action setpieces, and lines of dialogue. It’s like opening a box of forgotten photographs.

In the case of Planet of the Apes — Franklin J. Schaffner’s 1968 original, not Tim Burton’s lousy 2001 remake — I was stunned to find a film far more stark, confident, somber, chilling, and stylish than the simplistic caricature to which I’d reduced it. My first encounter with Planet of the Apes came sometime in the mid-1970s, when it ran as part of “Ape Week” on our local ABC affiliate’s Four-O’Clock Movie. I’d get home from school in time to watch an hour or so of cartoons before the feature came on; Ape Week was just one of several themed lineups I looked forward to eagerly, including “James Bond Week” and “Monster Week” (a string of Eiji Tsuburaya‘s Godzilla and Mothra movies).

The Apes series was a perfect fit for the Four-O’Clock Movie because there was one for every day of the week: from Monday’s installment of the first film through Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970) on Tuesday, Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971) on Wednesday, Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (1972) on Thursday, and Battle for the Planet of the Apes (1973) on Friday. The end of the week didn’t mean an end to Apes, though. Right about that time, a live-action TV series aired, followed by an animated counterpart on Saturday mornings. It would be thirty years before I heard the term transmedia franchise, but — along with daily reruns of the original Star Trek series — Apes was my inaugural passport to the labyrinthine landscape of distributed science-fiction storyworlds.

What I loved about Planet of the Apes back then, and what has stayed with me over the years, can be summarized in two images that sent me into an ecstasy of eeriness: the ape makeup created by Ben Nye and implemented by John Chambers; and the famous final shot, in which the hero Taylor (Charlton Heston) stumbles across the ruins of the Statue of Liberty and realizes he’s been on Earth — not an alien world, but his own home — all this time. The frame is below; a grainy YouTube version can be found here.

It’s one of the great twist endings in SF — contributed, fittingly enough, by Rod Serling. But its unfortunate effect was to instantly reduce the movie to a grand cliche, a semiotic Shrinky-Dink, source of endless quotations and parodies in the decades that followed. The sad truth about twist endings is that they follow a logic opposite that of genre (in which the same patterns reappear over and over again without anyone taking offense; we applaud them, in fact, for their iterative familiarity): once given its Big Reveal, a twist shrivels on the vine, spoiled by critics, lampooned for its very memorability. Citizen Kane‘s Rosebud, The Sixth Sense‘s dead psychiatrist, St. Elsewhere‘s world-in-a-snowglobe — each exists, like Taylor’s final, horrible epiphany, as the ultimate self-annihilating closure, shutting down not just a particular narrative instance, but the possibility of its own resurrection in anything but smirkily insincere form. Shots like the one that concludes Planet of the Apes are, to me, a perfect example of Lacanian captation: they arrest and hold us in an escape-proof hermetic prison of the imaginary.

OK, psychoanalytic blather aside, what was so great about watching Planet of the Apes again? I suppose my answer is yet more Lacan, for both the apes and humans are trapped by and within their own misrecognitions. Taylor and his fellow astronauts firmly believe themselves to be on an alien planet, despite evidence to the contrary (the apes speak English); for their part, the apes see the humans as completely Other and cannot countenance any notion that there is an evolutionary link between them. It’s a comedy of evolutionary errors, the Scopes Trial replayed simultaneously as farce and deadpan drama. The truth of the situation is hidden, like the purloined letter, in plain sight; it is not until the end, in a traumatic confrontation with the Real, that Taylor traverses his fantasy. (Maybe that’s why the joke has been replayed so frequently in pop culture, from Spaceballs to The Simpsons; what is repetition but the insistent revisiting of trauma?) Of course, as often occurs in science fiction, the meta-misrecognition that operates here is failing to see in the portrayal of a “future” the actual representation of a “present.” Eric Greene’s Planet of the Apes as American Myth explores this aspect of the film and its sequels, arguing that Apes is a funhouse mirror held up to racial politics in the United States.

Bringing this all back home to the movie and its special effects, I see two kinds of misrecognition at play in the visuals, both of them integral to the suspension of disbelief by astronauts, apes, and audiences alike. First, of course, are the actual human beings (Roddy McDowell, Kim Hunter, Maurice Evans) beneath the prosthetics and hair appliances. The makeup and costumes that turn these actors into sentient, speaking apes do not mask or muffle the performances, but rather estrange and amplify them: we watch and listen for nuances of emotion, an amused glint in the eye, a subtle shift in intonation, precisely because they are cloaked in filmmaking technology. At first glance the masquerade is comical, almost grotesque, but it quickly gives way to some remarkably graceful performances. Our twinned awareness of the trickery and investment in the fantasy reflects the knife-edge calibration of disbelief attending the finest FX work.

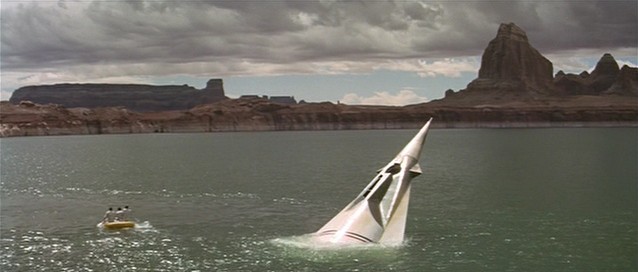

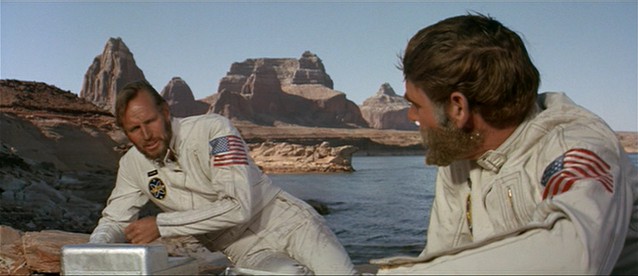

But there’s a second register of misrecognition here, one I would have missed completely if I hadn’t been watching a pristine widescreen transfer of the film. The first act of Planet of the Apes consists of Taylor and his fellow astronauts trekking across the forbidding but beautiful scenery of Arizona and Utah — in particular, the area of the Colorado River known as Lake Powell:

I was dumbstruck by this natural backdrop of mountains, deserts, and water, as gorgeously alien as anything in Nicolas Roeg’s Walkabout (1971). It occurred to me that the genius of this portion of the movie — an opening thirty minutes before the apes even show up — is that it places the spectator in a homologous position to the stranded astronauts. Like them, we stare at a world that is at once ours and another’s; a landscape both earthly and unearthly. Like the ape makeup, the cinematography forces us into sublime attentiveness, consuming every detail of a setting made familiar by our experience with terrestrial features, then unfamiliar through a storyline that presents it as an alien world, then familiar again in the final beachside revelation.

I guess what I’m saying with all this is that Planet of the Apes stands out to me as much for its planet as for its apes; and that in both constructs (and our response to them) we glimpse something of the multitiered, shuttling structure of belief and disavowal that great special effects provoke.

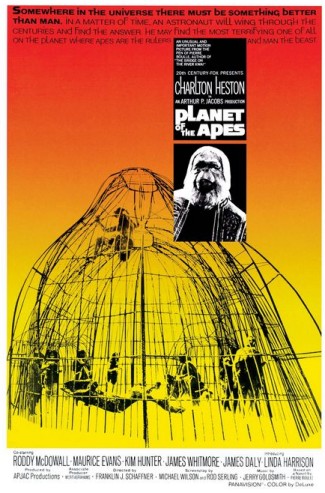

Love that poster — don’t think I’ve ever seen that before.

This is a franchise I admit that I’m not very familiar with — but I hope to become more so in the near future; although I know all of the sequels were distinctly different animals (no pun intended) than the first film. I haven’t watched the original “Apes” since I was a kid on television, and even then I’m not sure I saw the whole thing; but I recently picked up the DVD box set of all the films for a very good price, so I look forward to digging into them later this year. Late last year I caught a bit of one of the later entries with Ricardo Montalban (“Conquest” ?) on BBC; it does stick in my memory, even though I had it on in the background and was only half-paying attention…

I really like your idea about the landscape; on immediate recognition I can think of Ang Lee’s Hulk, the concluding bits of Star Trek V, and yes, Burton’s Apes redux as some of the only contemporary mainstream Hollywood films in my memory that feature such landscapes similarly, if not quite as meaningfully photographed (Word is J.J. Abrams has filmed some grand stuff out in the deserts of California for the new “Trek” film, in some of the same locations that Trek has used previously to represent Vulcan, I think). I kind of miss the great landscape shooting that we don’t seem to see so often anymore — with much of the Hollywood product shot in Vancouver or (studios in) Australia, I’m getting a little sick of seeing the same old Vancouver forests and pseudo-cityscape sets.

[Can you tell me how you capture film stills, by the way?]

I’m not ashamed to admit that I really enjoy all of the “Ape” elements of Burton’s “re-imagining” — particularly Tim Roth and Helena Bonham Carter (and Heston’s cameo – really interesting in its irony!). I really responded to their through-the-makeup performances (yes, in a good way); and if fact, I would argue that the “Ape” performances in Burton’s film are equally as interesting as any of those in the original film series. And Danny Elfman’s score I feel is one of his most unique and interesting. But yes, all the rest, including all the human elements, are pretty much rubbish; definitely one of Burton’s most soulless movies.

Did “St. Elsewhere” really end in a snowglobe??

_Beneath the Planet of the Apes_ holds a special place in my memory because that was where I first learned about the threat of nuclear arms (as I mentioned in that photo-comic I sent you.)

Re: growing up in SE MI in the 70s and watching genre movies on TV — I’m feeling lazier than usual today, so I’m going to paste something I wrote on another site on the occasion of the death of Sir Graves Ghastly last April:

Good ol’ Sir Graves! I almost never watched the movies he showed, but I’d sometimes watch the opening gags he’d do. I wonder what “the Ghoul” is up to these days?

You never know what you have ’til it’s gone. Back in the day, there used to a lot more movies on broadcast TV. I remember Bill Kennedy showing those old film noir classics around 1pm on WKBD channel 50 (“the Kaiser”), and the afternoon movies on channel 7. At the time, though, I didn’t appreciate old movies. I almost never watched Bill K. and only watched the channel 7 movies during “Monster Week”, when they showed Godzilla movies, and “Planet of the Apes” week. By the time I acquired a taste for those old movies, those movie shows had been replaced by Oprah and her ilk. Now a person has to get cable or find a decent video store to see those movies.

Michael: I use VLC for my screencaps, though the frame-by-frame navigation is imprecise. My application of choice used to be PowerDVD, but under the latest Windows XP patches, that program no longer runs — aargh! These are PC solutions, of course; in Mac environments I use the built-in DVD player and a tiny freeware frame grabber whose name I’m currently blanking on.

So you liked Burton’s Apes, eh? I’ll have to take a second look. I think I’ve enshrined the 1968 film and its sequel chain to the degree that no remake could measure up, but that doesn’t mean my mind is *completely* closed …

Re: landscapes in SF film, I’ve always wanted to write about the environments in the first Star Wars trilogy (Eps 4-6) versus the digital-backlot equivalents in Eps 1-3. I’m leery of replaying yet another round of the practical-vs-digital debate, but I can’t shake the sense of reality that the environments of Tunisia, Norway, the Pacific Northwest, etc. lent those films — in contrast to the blah CG spaces of Naboo and Coruscant. (True, there were artificial-natural settings in Eps 4-6 — Dagobah, for example — and Lucas used Tunisia again for Tatooine in the prequels. But still.)

Re: St. Elsewhere, you’ll just have to watch for yourself! It’s a great series, one of my favorites from the 80s.

Mike, so glad you brought up Sir Graves Ghastly and The Ghoul. These horror-movie hosts have been coming up in conversations lately with synchronistic consistency. Someone needs to do a project! And I do remember your comic on Beneath‘s underground Church of the Apocalypse — it’s one of the things that reinvigorated my interest in the Apes films.

The St. Elsewhere ending didn’t really remap my view of the series because it felt so self-evidently false, an afterthought. The others you cite, though, you’re completely right about: once seen, they cannot be unseen, and they tend to reduce all that came before to mere prologue. And you’re completely right about how much you then miss out on–the opening trek through Powellworld is totally one of the most spellbindingly “alien” representations that I can think of, completely eerie. (The score in those scenes helps a lot with that sensation.)

This also makes me think a bit of the ongoing fan reactions to Crystal Skull, which echo your thinking about location in Episodes 4-6 of Star Wars, lots of complaints about the loss of that sense of presence and tangibility to digital representations.

I think one way to think about that sensation is that the real settings seem to have the capacity to surprise or awe the audience without feeling “authored”. This is, as with photography, a misleading sensation–pull the camera back on the Tunisian settings of Episode 4 like Aunt Beru and Uncle Owen’s farmstead and they look rather differently, obviously. But there’s still some difference between framing and creating.

No, you’re right about St. Elsewhere‘s final scene — it was a curious moment, a “huh” moment, but little more. I suppose most endings of the “It was all a dream” variety feel like cheats rather than truly shocking twists (beginning fiction writers often use it, making the mistake of thinking they’ve rediscovered the wheel, until they learn better). Maybe because we’re already invested in one kind of dream — the story itself — so that to suddenly shell out to a meta-reality feels unexceptional.

Agree completely about the importance of Planet of the Apes‘s music; it was an early one from the great Jerry Goldsmith, who went on to compose some of my favorite film scores, including Capricorn One, Alien, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Innerspace, and (much later) The Mummy.

The point about authored vs. unauthored settings is interesting. On one hand, yes, Crystal Skull‘s blended CG/practical environments are like those of the prequels in their plastic unconvincingness (though Crystal Skull bothered me less, because I chose to interpret it as intentional pulp — unlike the recent Star Wars films, which seemed like earnest but spectacularly unsuccessful attempts to awe). On the other hand, the issue never seems to come up in regard to the most authored cinematic environments out there: the diegeses of things like WALL-E and Kung-Fu Panda. Such CG settings have precedents in predigital animation, of course, but something about the 3D-ness and cartographic consistency of the Pixar and DreamWorks spaces brings them much closer to the kinds of passing-for-live-action digital backlot work that has fans in an uproar. Yet no one points at WALL-E‘s world and cries “fake!” (except offended conservatives, and they’re talking about ideology, not environmental realism).

So I dunno: where do we draw the lines? How do we taxonomize these hybrid spaces? And at what point does framing give way to creating?

It’s all creating. A lot of it is framing, too. Pixar’s movies work because they completely establish a universe within their own digital fabric. The problem is getting a digital fabric to work with live-action elements and “real” actors. It’s also very difficult to convince the audience when they nowadays hear so much about the pre-production of the movie online and on chat shows. Things like Sky Captain are interesting experiments, but it’s still hard to completely manage these “hybrid” worlds, I’d argue. Even certain shots and small bits of Lord of the Rings bug me, despite the film’s overall excellent integration of practical and digital techniques. Personally, I find Pixar’s movies incredibly romantic as well (although maybe this is all in the scripts), so much so that I find them hard to watch without a “significant other.” There, you’ve learned something else new about me today. 😉

Actually I’m going to go one further and argue that, no, the “romantic” feeling I get in/from Pixar films is due to *more* than just the script — it is possibly due to the very conception and fabrication of characters and environments in their own unique and special way, in other words, yes, “authored.” There’s a reason why these movies have been so successful, and I’d argue that it’s something more than just what’s on the surface.

Nice POTA post. I just screened it last week for my Futurism class, touching on some of the notions of spatial and temporal defamiliarization that you note here. Interestingly, as much of Conquest was shot on the UCI campus, I showed that as well, adding an entirely new dimension to the classroom discussion.

Brilliant cinematography by Leon Shamroy, deft direction by the underrated Franklin J. Shaffner, and, yes, an inspired percussive score by Jerry Goldsmith.

By the way, though it fits so neatly with our general understanding of Rod Serling, he didn’t come up with the twist ending. The meat-and-potatoes of the script, including the twist (which Pierre Boulle hated), came from Michael Wilson (though it remains debatable as to who originated the notion of Taylor finding the Statue of Liberty – both Serling and producer Arthur P. Jacobs claimed they thought of it). Serling added some of the more obvious and rather forced dialogue when he was hired to “clean up” Wilson’s script. (The opening sequence of the film is also interesting in this respect, as it seems to be anticipated by a 1960 episode of The Twilight Zone titled “I Shot an Arrow into the Air.” In it four astronauts believe they have crashed onto a desert planet and kill each other for their small water reserves. The surviving astronaut then stumbles over a dune to be confronted by a highway and sign for Las Vegas. It’s worth noting that this was a story by Madelon Champion, not Serling.)

As for other films that effectively use a natural landscape, I never stop being impressed by the Vermont setting of Hitchcock’s woefully under-appreciated “The Trouble With Harry.”

One curious thing about WALL-E that I noticed, though, was the strong visual resemblance to some of the sub-mediocre film Idiocracy. Given what I think is an overlap in production between the two, I don’t think it’s deliberate, more an accidental convergence. But clearly as far as audience reaction goes, it has more to do with the frame that audiences are trained to watch: animation isn’t forced to by audiences to climb out of the uncanny valley until it starts to creep towards photorealism not just in its technology but also in the typological claims it makes about itself. You’re really thinking about an unravelling of the historical training of audiences, and about what will happen when audiences stop “remembering” a categorical distinction between animation and live-action, or “real” settings and CG settings.

Hello Bob.

I too am enthralled by the original movie.

My father took me and my three older brothers to see it when is first appeared at the cinema in Brisbane, Australia. I was about 7 years old, can you believe how lax the laws were back then and my dad was friends with the fella at the theatre. To me the most startling visual aspect of the movie was the opening 30+ minutes. I still watch it when it is aired in TV.

But there is nothing like the spectacle of the big screen, huge sound reverberation and sitting the dark engulfed by those images.

Superb film.