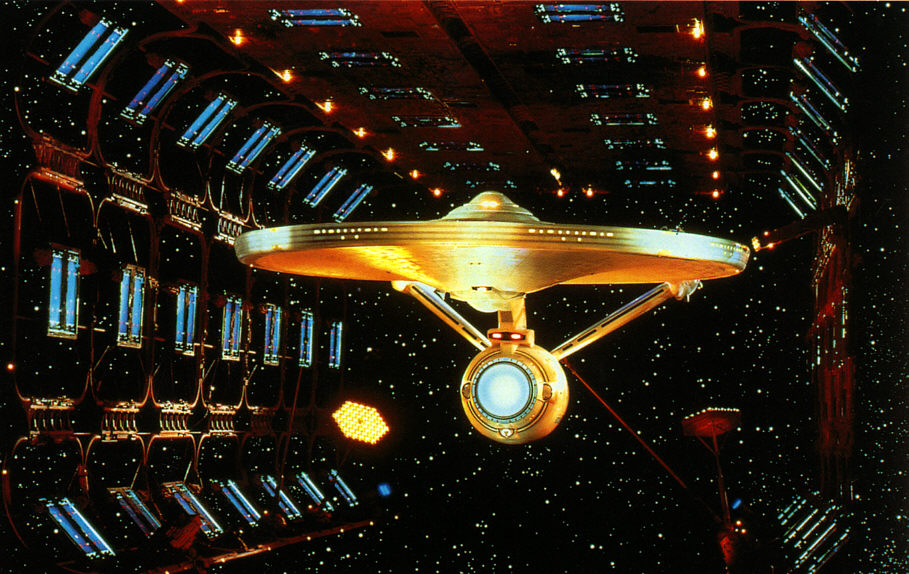

The teaser for J. J. Abrams’s Star Trek reboot, previously playing only to privileged viewers of Cloverfield, is now available for global consumption and scrutiny on Paramount’s official movie site. My own attention — and imagination — are captured less by the teaser’s aural invocations of real and virtual history (oratory by John F. Kennedy and Leonard Nimoy, the opening strains of Alexander Courage’s Trek score, even a weird snippet of the transporter sound effect) and more by the big eyeball-kick of a reveal that arrives at the end: the Enterprise itself, “under construction” (screen grab above).

Those two words close out the teaser and also adorn the website, clearly inviting us to indulge in the metaphorical collapse of film and starship. In Trek‘s calculus of the imaginary, this is nothing new; from the franchise’s 1966 “launch” onward, a happy equation — perhaps homology is the better term — has existed between the various televisual and filmic incarnations of Trek and the spacefaring vessel that is its primary characters’ means of exploration. The Enterprise, in other words, has always served as something akin to the gun-gripping hand at the bottom of the screen in a first-person shooter: an interface between our world and fictive future history, a graphic conceit easing us over the screen border that separates living room from starship bridge. (It’s not an original insight on my part to point out that Kirk and crew seek out strange new worlds while essentially sitting on comfy recliners and watching a big-screen TV.) Befitting their status as new textual “technologies,” each installment of the franchise has redesigned the Enterprise slightly, even given us new ships in which to take our weekly voyages: the Voyager, the Defiant, and all those goofy runabouts on Deep Space Nine.

In recent weeks I’ve grown weary of contemplating the ingenious, demonic ways in which Abrams builds interest in his projects, using feints and dead-ends to set us buzzing with anticipation and antagonism toward experiences that lie buried in our future (what the Cloverfield monster looks like, what’s really going on on Lost, and so forth). Every dissection of the Abrams effect, it now seems to me, just adds to the Abrams effect; the name of the game in a transmedia age is the viral replication of text, cultivation of mind-share expertly timed to the release calendar. In the end it doesn’t really matter whether our chatter is in the service of bunking or debunking. It’s all, in the eyes of the media industries, good.

So I think I’ll sidestep the argumentative bait offered by the teaser image, namely the degree to which Abrams’s Enterprise is faithful — or not — to the Enterprise(s) of history. Suffice to say that the ship hasn’t been reinvented to the egregious extent of the Jupiter II’s makeover in the 1998 film version of Lost in Space (a sin against science fiction for which Akiva Goldsman has partly compensated with the impressive I Am Legend). From the head-on view we’re given, the new Enterprise maintains the classic saucer-and-twin-nacelles configuration of Walter “Matt” Jefferies’s 60s design, which is good enough for me.

What I will point out is how insistently the “under construction” trope has recurred in Star Trek‘s big picture — its diegesis, metatext, or whatever we’re calling the giant mass of still and moving images, documents and data, that constitute its 42-year-old corpus. Scenes where the ship is in drydock abound in the movies and more recent TV series. 1979’s Star Trek: The Motion Picture, the first viable expansion of the franchise and proof of its ability to endlessly regenerate itself, contains an extended sequence in which Kirk and Scotty circle the under-construction Enterprise-A.

This rhapsodic interlude, derided by many critics and even some fans as evidence of ST:TMP‘s visual-effects metastasis — the elephantine marriage of budgetary excess and narcissistic self-indulgence — seems, over the years, to have undergone a kind of greening, emerging as the film’s kernel of authentic Trek, the powerfully beating heart (throbbing dilithium crystal?) of what is otherwise a rather gray and inert film.

And this image, from the 2005 Ships of the Line calendar, even more succinctly pinpoints the lovely lure of a starship under construction. “Christopher Pike, Commanding” and the class of favored images it exemplifies are like Star Trek‘s primal scenes. Often generated by nonprofessionals using 3D rendering programs, they are what inspired me to write a dissertation chapter about Star Trek‘s “hardware fandom” — those who spend their time buying blueprints of Constitution-class starships, doodling D7 Klingon cruisers and Romulan Birds of Prey, building model kits of the Galileo-7 shuttlecraft, and taping together cardboard-tube and cereal-box mockups of phasers, communicators, and tricorders.

All of those objects were imperfect, and none quite measured up to the onscreen ideal. But it was their very imperfections — their under-constructedness — that marked them as ours, as real and full of possibility. Better the dream of what might come to be then the grim result of its arrival. When it comes right down to it, the Enterprise is always being built, always under construction. I don’t mind waiting another year with the partial version that Abrams has given us.

“the ship hasn’t been reinvented to the egregious extent of the Jupiter II’s makeover in the 1998 film version of Lost in Space (a sin against science fiction for which Akiva Goldsman has partly compensated with the impressive I Am Legend).”

…Yet Akiva will never make up for the sins he committed by writing “Batman & Robin”…

😉

Nice optimistic analysis of the teaser, Bob.

Michael, you’re right — Akiva Goldsman retains his crown as antichrist. And of course we must not forget A BEAUTIFUL MIND.

I’m glad you liked the analysis — actually, I meant to give you a shout-out in it for your excellent chapter on digital reinventions of the Enterprise. That ship has borne quite the burden of semiosis over the years!

Why does Akiva Goldsman get scripts? Seriously, one of the great mysteries of our times. In 500 years, that will be the basis of a fiction rather like the Da Vinci Code, an obscure mystery of which much can be made.

I keep hoping that the next moldering box in the garage that my mom goes through in the slimming down of her inventories will have my Star Trek blueprints set in them. Jebus, that was the greatest Christmas ever.

The new remastered Star Trek original series episodes are a very interesting piece of this puzzle.

There has certainly never been a more pornographic use of special effects than the extended Enterprise fly-around scene in ST: TMP. And I mean that seriously.

Tim, I assume your DA VINCI CODE reference was an elaborate intertextual joke — since Goldsman wrote the screenplay for the film — thus replicating in miniature the whole clues-buried-in-plain-sight vibe of that story? Or am I reading too much into it?

Regarding Trek blueprints, I somehow managed to hold onto the General Plans for the U.S.S. Enterprise and the Technical Manual, both of which came out in 74-75, when I must have been — jeez — nine years old. Got ’em in my office if you want to borrow them!

Agree about the remastered episodes; alongside them I see the fan-produced New Voyages, with their very handsome digital recreations of the old-school miniatures, as key to understanding what Trek has become.

The code of the code. Golds man. Man of Gold? Man of Code? Akiva. A kivu–a ruined structure indigenous to America. Inside the script a labryinth. Lose money? But make money! How?

Tim, thank you for your comment.

I have dispatched an albino monk assassin to kill you.