[Warning: this review contains spoilers — and at the end, a blue penis.]

One wonders if Masahiro Mori, the roboticist who introduced the term “uncanny valley” in 1970, now wishes he’d had the foresight to trademark it; after laying largely dormant for a couple of decades, the concept came into its own, bigtime, with the advent of photorealistic CG. Or perhaps I should say CG posing as photorealistic, for what nearly passes muster in one year — the liquid pseudopod in The Abyss (1986), the lipsynched LBJ in Forrest Gump (1994), the entire casts of Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within (2001), The Polar Express (2004), and Beowulf (2007) — lapses into reassuringly spottable artifice the next. The only strategy by which CG convincingly and sustainably replicates organic life, in fact, is Pixar’s, and their method is simultaneously a cheat and a transcendent knight’s-move of FX design. Engaging in what Andrew Darley has called second-order realism, Pixar’s characters wear their manufactured status on their skin, er, surface (toys, bugs, fish, cars) while drawing on expressive traditions derived from cel- and stop-motion animation to deliver believable, inhabited performances and make us forget that what we’re watching are essentially, with their sandwiching of organic and synthetic elements, cyborgs.

Of course, by casting its films in this manner, Pixar retreats from true uncanniness. Humanity has always been an easier sell when it comes to cartoonish abstractions; ask anyone from Pac-man to Punch and Judy. The uncanny valley actually kicks in when a simulation comes close enough to almost fool us, only to fall back into uncomfortable, irreducible alterity. Such is the fate, I think, of Watchmen.

That calm, urbane salon that is the internet is already abuzz with evaluations of the movie adaptation of Alan Moore’s and Dave Gibbons’s graphic novel — actually, it’s been buzzing for months, even years, another instance of what I have elsewhere termed the cometary halo that precedes any hotly-anticipated media property. Fans have been speculating, cogitating, and arguing about the whys and wherefores of overnight techno-auteur Zack Snyder’s approach for so long that the arrival of the film itself marks the conversation’s end rather than its beginning. The Christmas present has been unwrapped; Schoedinger’s Cat is out of the box; we’ve traveled into the Forbidden Zone only to learn we were on Earth the whole time.

My own take on Watchmen is that it’s an impressive feat of engineering: detailed, intricate, and surprisingly unified in tone. Beyond a splendid opening-credit sequence, however, it isn’t particularly invigorating or dramatic — hell, I’ll just say it, the thing’s boring for long stretches. As Alexandra DuPont, my absolute favorite reviewer on Ain’t-It-Cool News, points out, the boring bits are unfortunately more prevalent toward the end, giving the movie as a whole the feeling of a party that peters out once the fun people leave, or a hot date that takes a wrong turn when someone brings up religion. (And while I’m linking recommendations, let me encourage you toward the smartest movie site out there.) Watchmen is still a rather miraculous object, an oddly introverted and idiosyncratic epic whose very existence lends support to the idea that fans have become an audience important enough to warrant their own blockbuster. Tastewise, the periphery has become the center; the niche the norm.

For Watchmen, love it or hate it, is fanservice with a $120 million budget. Let’s remember that to hardcore fandom, love and hate are as difficult to disarticulate as the tattoos on Harry Powell‘s knuckles; the object is never simply accepted or rejected outright (that’s a mark of the fickle mainstream, whose media engagements resemble one-night stands or trips to the drive-through) but instead studied and anatomized with scholarly rigor, its faults and achievements tabulated and ranked with an accountant’s thoroughness. Intimacy is the name of the game — that and passing the object from hand to hand until it is worn smooth as a worry bead. I’ve no doubt that Watchmen will be worried to death in coming weeks, the only thing keeping it from complete erasure the periodic infusion of new material: transmedia expansions like Tales of the Black Freighter, or the four-hour director’s cut rumored to be lurking on Snyder’s hard drive.

The principal focus of all this discussion will undoubtedly be the pros and cons of adaptation, for that is the process which Watchmen foregrounds in all its contradiction and mystery. Viewing the film, I thought irritably of all the adaptations to which we give a free pass, the ones that don’t get scrutinized at a subatomic level: endless versions of Pride and Prejudice, and let’s not forget that little gift that keeps on giving, Romeo and Juliet. Shakespeare, it seems to me, is as viral as it gets, and Masterpiece Theater a breeding ground that could compete with Nadya Suleman‘s womb. Watchmen simply takes faithfulness and fidelity to a cosmic degree, its mise-en-scene a mimetic map of the printed panels that were its source.

Or source code; for what Synder has achieved is not so much adaptation as transcription, operationalization; a phenotypic readout of a genetic program, a “run” in cinematic hardware of an underlying instruction set. Watchmen verges, that is, on emulation, and its spiritual fathers are not Moore and Gibbons but Turing and von Neumann. Snyder probably thought his hands were tied; there’s no transposing Watchmen to a new setting without disrupting its elaborate weavework of political and pop-cultural signifiers. The origin of the story in graphic form means that cinema’s primary ability, visualization, had already been usurped; faced with a publicly-available reference archive and a legion of fans ready to apply it, Synder may have felt his only option was to replicate down to the tiniest prop and wardobe detail what’s shown in the panel. Next level up is the determining rhythm of Moore’s scripting: storytelling and dialogue have been similarly transposed from printed page to filmed frame, and while some critics laughingly excoriate Rorschach’s purple prose, his overheated voice-overs sounded fine to me (Rorschach’s a rather self-important character, after all — as narcissistic and monomaniacal in his way as the ostensible villain Ozymandias). Editing, too, copies over with surprising fluidity: some of the most effective sequences, like the Comedian’s funeral interwoven with flashbacks to his ignoble career, or Jon Osterman’s tragic temporal tapestry of an origin story, are crosscut almost precisely as laid out on the page.

What’s left to Synder and the cinematic signifier, then, is a handful of sensory registers, deployed sometimes with subtlety and sometimes an almost slapstick obviousness. Music plays a crucial role in the film, as does the casting; some choices are dead-on effective, others (Malin Akerman, I’m looking at you — with sympathy) not so much. The most talked-about aspect of Synderian style is probably his use of variable speed or “ramping,” and on this front I’m with DuPont: the effect of all the slow-mo is to suggest something of the fascinated readerly gaze we bring to comic books, lingering over splash pages, reconstituting in our internal perceptions the hieroglyphic symbolia of speed lines and large-fonted “WHOOSHES.”

But back to the uncanny valley. The world of Watchmen is undoubtedly digital in ways we can’t even detect; there are certainly some showstopping visual moments, but I’d argue that more important to the movie’s cumulative immersive impact are the framing, composition, and patterns of hue, saturation, and texture that only a digital intermediate makes possible. It’s less garish than Sin City, and nowhere near the green-screened limbo of Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow, but all the exterior shots and real-world sets shouldn’t blind us to the essential constructedness of what we’re seeing.

And here’s where the real uncanniness resides. We’re often hoodwinked into thinking that the visual (indeed, existential) crisis of our times is the rapidly closing gap between profilmic truth and what’s been simulated with computer graphics. But CG is merely the latest offspring of a vast heritage of manipulation, a tradition of trickery indistiguishable from cinema itself. Watchmen is uncanny not because of its visual effects, but because it comes precariously close to convincing us that we are seeing Moore’s and Gibbons’s graphic novel preserved intact, when, after all, it is only a copy — and a lossy one at that. In flashes, the film fools us into forgetting that another version exists; but then the knowledge of an original, an other, comes crashing back in to sour the experience. It is not reality and its digital double whose narrowing difference freaks us out, but the aesthetic convergence between two media, threatening to collapse into each other through the use of ever more elaborate production tools and knowing appeals to fannish competencies. At stake: the very grounds of authenticity — the epistemic rules by which we recognize our originals.

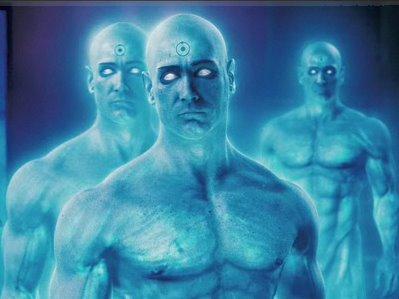

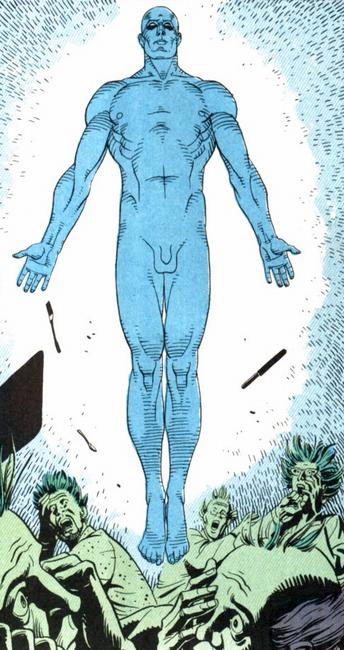

I’ll conclude by noting that the character who most fascinated me in the graphic novel is also the one I couldn’t tear my eyes from onscreen: Dr. Manhattan. He’s “played” by Billy Crudup, and as I noted in my post on Space Buddies, the actor’s voice is our central means of accepting Manhattan as a living character. Equally magnificent, though, is the physical performance supplied by Manhattan’s digital surface, an iridescent azure body hanging from Crudup’s motion-captured face. Whether intentionally or through limits in the technology, Dr. Manhattan never quite fits into his surroundings, and that’s exactly as it should be; as conceived by Moore, he’s a buzzing collection of hyperparticles, a quantum ghost, and Snyder uses digital effects to nail Manhattan’s transhuman ontology. (He is, both diegetically and non-, a walking visual effect.) Presciently, the print version of Watchmen — published between 1986 and 1987, when CG characters were just starting to creep into movies (see Young Sherlock Holmes) — gave us in Dr. Manhattan our first viable personification of digital technology. The metaphysical underpinning and metaphorical implications of the print Manhattan, of course, are radioactivity and the atomic age, not digitality and the information revolution. But in the notion of an otherwordly force, decanted into a man-shaped vessel but capable of manipulating the very fabric of reality, they add up to much the same: Dr. Manhattan — synthespian avant la lettre.

I guess you don’t want to know that I read to the end just to see the blue penis.

On the contrary — this knowledge made my day.

Now that’s what we call a “man-shaped vessel”, Bob. The first CGI willy in a Hollywood movie? (I think Irreversible has that honour in Europe, though I’ve not done much research on the matter)

Hi, Bob…

Love this review, esp. the speculations on emulation. Good stuff.

Cheers.

-j

Dan: I don’t know of any other specifically digital augmentations of the male anatomy — though Mark Wahlberg did wear a latex, uh, prosthesis in Boogie Nights. (Hmm. There’s got to be a paper in here somewhere.)

John: thanks so much! I liked your Watchmen review a great deal as well …

Of course one of the big points in the fan debate out there is the decision to NOT use CGI to represent the giant Cthuhluoid-squid-vagina of the original graphic novel, and change the conclusion rather substantively. Ok for blue penises, not for alien vagina monsters. Hm.

Anyway, great essay, one of your best here.

I agree, Tim: the filmmakers’ decision to jettison the squid is supremely odd, if only because of the rest of the enterprise’s relentless fidelity. (Viewed in this light, maybe all the detail is a guilty overcompensation?) I chose not to tackle this key elision of the film, not because it isn’t interesting, but just the opposite — it’s a huge symptom of something, I’m just not sure what.

If pressed, I’d suggest (glibly) that New York’s destruction by manufactured psychic squid becomes “unsayable” in the aftermath of 9/11 — itself a catastrophe that seemed, at least in America’s immediate characterization of it, beyond comprehension, as illegible as an staged alien invasion. Sadly funny that, in Moore’s forecast, such an event would unify the planet rather than triggering more scorched-earth foreign policy. And a logical but disappointingly conservative decision by Snyder and screenwriters Hayter and Tse to substitute Dr. Manhattan as the supposed external threat.

I suspect we’ll be seeing a “fan edit” sometime soon that restores the squid to its rightful place — perhaps this is already the case with the motion comics, which I haven’t had a chance to check out.

Your observation about the uncanny trickery at work in Watchmen is quite brilliant. Thanks for this thorough discussion of the depth of this film adaptation. You’ve given me a new way to think of Dr. Manhattan, too, when I revisit the film!