Thanks to an incredibly generous gift certificate from some friends, my wife and I spent last weekend at a ritzy hotel in Washington, DC – where the 100-degree temperatures made us quite happy to stay inside, work out in the fitness center, order room service, and watch TV.

But the one time we had to venture outside was to visit the National Air and Space Museum, my favorite spot in Washington and, perhaps, the greatest place in the known universe. Ever since I first visited DC, at nine or ten years old, I have loved the NASM: the satellites suspended from the ceiling, the Imax theater, the giant Robert McCall mural, the silver packets of freeze-dried ice cream, and of course the full-size Skylab sitting on its end like a small cylindrical skyscraper, a constant line of people threading through its begadgeted, submarinelike innards.

I’ve been to the museum several times, so it was a shock to come face-to-face with one of its most famous artifacts, and realize that – somehow – I’d forgotten it was there. It used to hang gloriously over the entrance to some special exhibit (Spaceflight in Science Fiction, maybe?), which has now been replaced by a room devoted to the role of computers in aeronautical design and engineering. As for the marvelous object, it has moved to the lower floor of the gift shop, where it sits toward the back in its own plexiglass box, big enough to hold a Hummer…

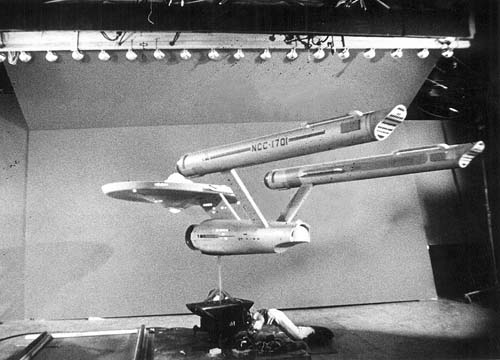

This is the original miniature of the U.S.S. Enterprise, used for optical effects shots in the first series of Star Trek (1966-1969). It’s been part of the Smithsonian collection since 1974, and has undergone several modifications in that time, including a new “mosaic” paint job to simulate square hull plating. (This concept, introduced with the starship’s redesign for Star Trek: The Motion Picture [Robert Wise, 1979], has since become standard for Trek’s vessels, reflected in the numerous sequels and series that constitute the franchise.)

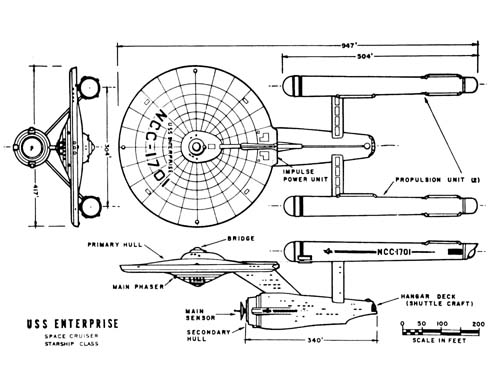

After gazing reverently at the Enterprise for a while, I dragged my wife over to see it. I explained to her – feeling somewhat like a goofball – that this was not just a replica or facsimile, but the actual shooting model that went before the cameras of the Howard Anderson effects company, to which Desilu Studios farmed out its optical work. (Actually, the miniature made the rounds of several FX houses, including Film Effects of Hollywood, the Westheimer Company, and Van Der Veer Photo Effects – Trek demanding a particularly high number of expensive and time-consuming optical effects.) Eleven feet long and weighing 200 pounds, the miniature is made of poplar wood, vacuformed plastic, and sheet metal. It was one of three Enterprises used in shooting (the others included a small balsa-wood version that appeared in the “swish” flybys of the title sequence, and a three-foot version used to show the ship in the far distance). It was designed by Walter “Matt” Jefferies in consultation with series creator Gene Roddenberry, and build by Richard C. Datin, Jr.

The miniature undeniably has a sad aspect to it now. Consigned to what is essentially the museum basement, it sits by a shelf of books about Star Trek and Star Wars like an aging carny hawking its wares. Once lit from within by a complex electrical system of lights and relays, it is now shadowed and gloomy, its sepulchral air made more poignant by the racks of day-glow flags, posters, and coffee mugs that surround it. (In this, the back corner of the gift shop, the air-and-space motif gives way to a randomly-themed grab bag of DC memorabilia: Washington Monument t-shirts, Abraham Lincoln yo-yos.)

Yet despite or perhaps because of the diorama of motley neglect in which I encountered it, the Enterprise miniature possesses an historical solidity, a gravity classifying it as the best kind of museum exhibit: one that belongs simultaneously to past and present, functioning as a material bridge between one moment in time and another. For as I circled the plexiglass case, snapping pictures with my digital camera, I realized that the real magic was not in seeing the Enterprise with my own eyes. It was, instead, in the act of capturing its image — of being physically present at one node of a visual apparatus, framing the model in my viewfinder and recording the light rays reflecting off its surface. In doing so, I fleetingly occupied the position of the original camera operators at Howard Anderson and Van Der Veer in Hollywood in the late 1960s, whose daily job it was to line up and shoot this structure of wood and plastic.

This, I suggest, is the real experience of the Enterprise. As a viewer growing up, watching the show on TV, I saw the starship only in its final composited form – as an “actual” vessel in space – experiencing a play-along immediacy that is the basic perceptual displacement necessary to the operation of television, movies, and videogames (we can only believe what we are seeing if we disbelieve in the fact of its having-been-made). Photographing the model at the National Air and Space Museum on Saturday, I experienced a flash of disbelief’s opposite, what I can only call mediacy, bringing layers of technology and labor – of historical material practice – back into the picture. It was like going to work and going to church at the same time, like punching a timeclock that is also a reliquary holding the bones of a saint. It was great; I’ll never forget it.

Your post made me wonder what the long-term curatorial destiny is for pop culture “relics” like these. We don’t know if King Kong and Star Wars will still have cultural currency in later centuries. The Enterprise certainly seems worth conserving to me, but what if museum visitors just aren’t familiar enough with an item to be interested in it? Will it be moved down to the storage room and forgotten?

King Kong and the Enterprise rotting away in some moldy cellar … Perish the thought, EB!

Actually, I think your question could apply to just about any cultural object, not merely the ones belonging to the realm of pop culture. As values, aesthetics, and epistemes shift, so do the practices by which once-cherished things are preserved and exhibited: some get the snazzy velvet cushion and marble pedestal treatment, others get shoved rudely away in a warehouse of crates like the one at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark. I imagine that part of the archeologist’s joy must be in stumbling across just such overlooked and neglected objects — treasures treated as trash — and restoring them to their “rightful” place of visibility (which of course will be renegotiated by future curators and audiences).

That said, artifacts of specifically popular culture do seem especially at risk, prone to being tossed aside. (I remember bagging up and throwing out dozens of issues of Famous Monsters of Filmland when I was about fifteen and “over” such childish things — a breathtakingly shortsighted action to me now.) Maybe our love for the entertainments of mass culture is unavoidably bound up with scorn? In which case, thank god for collectors like Bob Burns, current owner of Willis O’Brien & Carl Delgado’s stop-motion armature of King Kong from 1933 …

Hi,

I was wondering if maybe you might help me locate the “Trek5.com” photos of Matt Jefferies’s Soundstage model. The Stage 9 / cardboard model that sold on eBay back in 2002.

I stumbled upon it one day but didn’t have the computer know how to hit the “save-as” feature. Transfered it to “my favorites” and sadly realized it was missing one day.

Have tried Profiles in history to no avail, as I guess they figure I’m out to “steal it” somehow!?! I don’t want to keep bugging them. I guess for some folks, a silent answer is understood by all to mean “NO.”

I realize my question is in no way related to your site, please forgive me I’m not sure of how to go about reaching anyone else.

Thank you very much,

Jonathan Bolz

Hi Jonathan. I was in the midst of writing back to you privately when I realized that the more “collectively intelligent” path was to post your question for other readers to see and, hopefully, help with. I’m afraid I don’t know of the Trek5 photos to which you refer, though I have squirreled away many dozens of Enterprise stills (both screen captures from the series as well as studio production shots). I can certainly send these on to you if you guide me a little more specifically. Which scale/version of the Enterprise miniature are you seeking? Are these screen caps or production stills?

In the meantime, can anyone else help Jonathan find the photos he’s looking for?

P.S. I think your question is absolutely related to the site. I’m glad you posted it.

Bob, I’m so sorry for not seeing this sooner!!! THANK YOU for posting it all the same.

The pictures I’m refering to are of Matt Jefferies, 1/4 scale model of the entire Stage #9 “Corridor” that he built at home by himself, in order to show the directors the dimentions & parameters of the sets on which they would be shooting.

All the rooms that were used for filming, he built in 1/4 (1/48th scale I guess), the transporter room, briefing rm, kirk’s quarters, engineering, sickbay etc.etc. and the main hallway. The base is painted flt. black with broken fire eng. red trim strips around the parameter. The bridge mock-up is sitting next to all this, in one of the corners.

I remember the person who took the photo’s, stated that he was observing this model on display before the auction was to take place. (sold on ebay back in: 2002 to the tune of $45,000.00 – $42,000.00) These were not professional photo’s, although they were done very professionaly!!! he had installed one of those + / -, zoom tools…so it was kind of like you were walking around the thing. WAY “2” COOL I tell ya !!!

The website title was: trek5/lower decks.com. http.this.that and the other thing{just kidding, you get the idea} If you want I can copy the address letter for letter, it’s still in my favorites.{everything but the pictures dammit}!

GOD help those people if they trash the 11 footer !!! I so hope maybe it will be up for grabs one day and that maybe GOD might grant me the responsability of caring for her.

P.s. – Everyone, PLEASE excuse my spelling and / or lack of it and / or desire to break out the dictionary !

Jonathan