Ordinarily I’d start this with a spoiler warning, but under our current state of summer siege — one blockbuster after another, each week a mega-event (or three), movies of enormous proportion piling up at the box office like the train-car derailment that is Super 8‘s justly lauded setpiece of spectacle — the half-life of secrecy decays quickly. If you haven’t watched Super 8 and wish to experience its neato if limited surprises as purely as possible, read no further.

This seems an especially important point to make in relation to J. J. Abrams, who has demonstrated himself a master of, if not precisely authorship as predigital literary theory would recognize it, then a kind of transmedia choreography, coaxing a miscellany of texts, images, influences, and brands into pleasing commercial alignment with sufficient regularity to earn himself his own personal brand as auteur. As I noted a few years back in a pair of posts before and after seeing Cloverfield, the truism expounded by Thomas Elsaesser, Jonathan Gray, and others — that in an era of continuous marketing and rambunctiously recirculated information, we see most blockbusters before we see them — has evolved under Abrams into an artful game of hide and seek, building anticipation by highlighting in advance what we don’t know, first kindling then selling back to us our own sense of lack. More important than the movie and TV shows he creates are the blackouts and eclipses he engineers around them, dark-matter veins of that dwindling popular-culture resource: genuine excitement for a chance to encounter the truly unknown. The deeper paradox of Abrams’s craft registered on me the other night when, in an interview with Charlie Rose, he explained his insistence on secrecy while his films are in production not in terms of savvy marketing but as a peace offering to a data-drowned audience, a merciful respite from the Age of Wikipedia and TMZ. No less clever for their apparent lack of guile, Abrams’s feats of paratextual prestidigitation mingle the pleasures of nostalgia with paranoia for the present, allying his sunny simulations of a pop past with the bilious mutterings of information-overload critics. (I refuse to use Bing until they change their “too much information makes you stupid” campaign, whose head-in-the-sand logic seems so like that of Creationism.)

The other caveat to get out of the way is that Abrams and his work have proved uniquely challenging for me. I’ve never watched Felicity or Alias apart from the bits and pieces that circulated around them, but I was a fan of LOST (at least through the start of season four), and enjoyed Mission Impossible III — in particular one extended showoff shot revolving around Tom Cruise as his visage is rebuilt into that of Philip Seymour Hoffman, of which no better metaphor for Cruise’s lifelong pursuit of acting cred can be conceived. But when Star Trek came out in 2009, it sort of short-circuited my critical faculties. (It was around that time I began taking long breaks from this blog.) At once a perfectly made pop artifact and a wholesale desecration of my childhood, Abrams’s Trek did uninvited surgery upon my soul, an amputation no less traumatic for being so lovingly performed. My refusal to countenance Abrams’s deft reboot of Gene Roddenberry’s vision is surely related to my inability to grasp my own death — an intimation of mortality, yes, but also of generationality, the stabbing realization that something which defined me as for so many years as stable subject and member of a collective, my herd identity, had been reassigned to the cohort behind me: a cohort whose arrival, by calling into existence “young” as a group to which I no longer belonged, made me — in a word — old. Just as if I had found Roddenberry in bed with another lover, I must encounter the post-Trek Abrams from within the defended lands of the ego, a continent whose troubled topography was sculpted not by physical law but by tectonics of desire, drive, and discourse, and whose Lewis and Clark were Freud and Lacan. (Why I’m so touchy about border disputes is better left for therapy than blogging.)

Given my inability to see Abrams’s work through anything other than a Bob-shaped lens, I thought I would find Super 8 unbearable, since, like Abrams, I was born in 1966 (our birthdays are only five days apart!), and, like Abrams, I spent much of my adolescence making monster movies and worshipping Steven Spielberg. So much of my kid-life is mirrored in Super 8, in fact, that at times it was hard to distinguish it from my family’s 8mm home movies, which I recently digitized and turned into DVDs. That gaudy Kodachrome imagery, adance with grain, is like peering through the wrong end of a telescope into a postage-stamp Mad Men universe where it is still 1962, 1965, 1967: my mother and father younger than I am today, my brothers and sisters a blond gaggle of grade-schoolers, me a cheerful, big-headed blob (who evidently loved two things above all else: food and attention) showing up in the final reels to toddle hesitantly around the back yard.

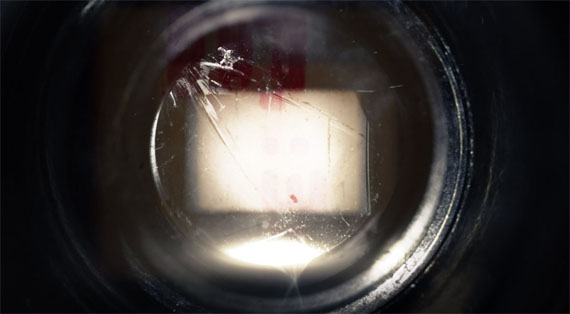

Fast-forward to the end of the 70s, and I could still be found in our back yard (as well as our basement, our garage, and the weedy field behind the houses across the street), making movies with friends at age twelve or thirteen. A fifty-foot cartridge of film was a block of black plastic that held about 3 minutes of reality-capturing substrate. As with the Lumiere cinematographe, the running time imposed formal restraints on the stories one could tell; unless or until you made the Griffithian breakthrough to continuity editing, scenarios were envisioned and executed based on what was achievable in-camera. (In amateur cinema as in embryology, ontology recapitulates phylogeny.) For us, this meant movies built around the most straightforward of special effects — spaceship models hung from thread against the sky or wobbled past a painted starfield, animated cotillions of Oreo cookies that stacked and unstacked themselves, alien invaders made from friends wrapped in winter parkas with charcoal shadows under the eyes and (for some reason) blood dripping from their mouths — and titles that seemed original at the time but now announce how occupied our processors were with the source code of TV and movie screens: Star Cops, Attack of the Killer Leaves, No Time to Die (a spy thriller containing a stunt in which my daredevil buddy did a somersault off his own roof).

Reconstructing even that much history reveals nothing so much as how trivial it all was, this scaling-down of genre tropes and camera tricks. And if cultural studies says never to equate the trivial with the insignificant or the unremarkable, a similar rule could be said to guide production of contemporary summer blockbusters, which mine the detritus of childhood for minutiae to magnify into $150 million franchises. Compared to the comic-book superheroes who have been strutting their Nietzschean catwalk through the multiplex this season (Thor, Green Lantern, Captain America et-uber-al), Super 8 mounts its considerable charm offensive simply by embracing the simple, giving screen time to the small.

I’m referring here less to the protagonists than to the media technologies around which their lives center, humble instruments of recording and playback which, as A. O. Scott points out, contrast oddly with the high-tech filmmaking of Super 8 itself as well as with the more general experience of media in 2011. I’m not sure what ideology informs this particular retelling of modern Genesis, in which the Sony Walkman begat the iPod and the VCR begat the DVD; neither Super 8′s screenplay nor its editing develop the idea into anything like a commentary, ironic or otherwise, leaving us with only the echo to mull over in search of meaning.

A lot of the movie is like that: traces and glimmers that rely on us to fill in the gaps. Its backdrop of dead mothers, emotionally-checked-out fathers, and Area 51 conspiracies is as economical in its gestures as the overdetermined iconography of its Drew Struzan poster (below), an array of signifiers like a subway map to my generation’s collective unconscious. Poster and film alike are composed and lit to summon a linkage of memories some thirty years long, all of which arrive at their noisy destination — there’s that train derailment again — in Super 8.

I don’t mind the sketchiness of Super 8‘s plot any more than I mind its appropriation of 1970s cinematography, which trades the endlessly trembling camerawork of Cloverfield and Star Trek for the multiplane composition, shallow focus, and cozily cluttered frames of Close Encounters of the Third Kind. (Abrams’s film is more intent on remediating CE3K‘s rec-room mise-en-scene than its Douglas-Trumbull lightshows.) To accuse Super 8 of vampirizing the past is about as productive as dropping by the castle of that weird count from Transylvania after dark: if the full moon and howling wolves haven’t clued you in, you deserve whatever happens, and to bring anything other than a Spielberg-trained sensibility to a screening of Super 8 is like complaining when Pop Rocks make your mouth feel funny.

What’s exceptional, in fact, about Super 8 is the way it intertextualizes two layers of history at once: Spielberg films and the experience of watching Spielberg films. It’s not quite Las Meninas, but it does get you thinking about the inextricable codependence between a text and its reader, or in the case of Spielberg and Abrams, a mainstream “classic” and the reverential audience that is its condition of possibility. With its ingenious hook of embedding kid moviemakers in a movie their own creative efforts would have been inspired by (and ripped off of), Super 8 threatens to transcend itself, simply through the squaring and cubing of realities: meta for the masses.

Threatens, but never quite delivers. I agree with Scott’s assessment that the film’s second half fails to measure up to its first — “The machinery of genre … so ingeniously kept to a low background hum for so long, comes roaring to life, and the movie enacts its own loss of innocence” — and blame this largely on the alien, a digital McGuffin all too similar to Cloverfield‘s monster and, now that I think about it, the thing that tried to eat Kirk on the ice planet. Would that Super 8‘s filmmakers had had the chutzpah to build their ode to creature features around a true evocation of 70s and 80s special effects, recreating the animatronics of Carlo Rambaldi or Stan Winston, the goo and latex of Rick Baker or Rob Bottin, the luminous optical-printing of Trumbull or Robert Abel, even the flickery stop motion of Jim Danforth and early James Cameron! It might have granted Super 8‘s Blue-Fairy wish with the transmutation the film seems so desperately to desire — that of becoming a Spielberg joint from the early 1980s (or at least time-traveling to climb into its then-youthful body like Sam Beckett or Marty McFly).

Had Super 8‘s closely-guarded secret turned out to be our real analog past instead of a CGI cosmetification of it, the movie would be profound where it is merely pretty. Super 8 opens with a wake; sour old man that I am, I wish it had had the guts to actually disinter the corpse of a dead cinema, instead of just reminiscing pleasantly beside the grave.

I found watching Super 8 an unusual experience. I’m a bit younger and I did make a couple films on vhs so I could relate to the story a lot. On the other hand the academic in me found the fact that the only 3 black people with speaking parts all died, the relative lack of any women and the fact that the boys had to rescule the helpless girl.

Regarding the look of the creature, I thought it looked like Cloverfield too. I was kind of hoping that it would secretly be a prequel or something.

I saw a lot of people online talking about the lens flares. I didn’t notice them really. What I did notice and found distracting was the use of shallow focus and pulling focus from a person in the foreground to one in the background.

Yep, the film definitely imports the biases and blind spots of the era along with its cars and hairstyles. I’m planning to write more about gender in Super 8 in an upcoming post.

I noticed the lens flares, but only because they’ve become a running joke in Abrams’s work (and recall specifically the blue flaring, signs of multiverse bleed, in Fringe). The shallow DOF and rack focuses are straight out of the playbook of Spielberg and his cinematographers.