This is the second of a series of posts on a new project of mine exploring movie-monster fandom and “kid culture” in the U.S. from the early 1960s onward. My focus will be less on monster movies themselves than on the objects that circulated around and constituted the films’ public — and personal — presence: model kits, toys, games, and other paraphernalia. Approaching media culture through its object practices, I argue, reveals a dynamic space of production in which texts, images, and objects translate and transform one another in flows of commodities, collectibles, and creativity. [Previous posts can be found here.]

Although Famous Monsters of Filmland launched its first issue in 1958, the figure that grounds this study — the Aurora line of plastic model kits based on classic movie monsters — did not appear there until the middle of 1962. Up to that point, the magazine’s “Monster Mail Order” pages featured a collection of materials sharing a vaguely horrific theme: shrunken heads, monster hands and feet, talking skulls, dangling skeletons, and — usually set off on a page of its own, bordered in black — a line of rubber masks that included Screaming Skull; Witch; Vampire; Igor; and Werewolf. By Issue 3 (April 1959), “monster stationery” and 3D comics had been added; by Issue 5 (November 1959), horror movies themselves joined the lineup, with full-length and abridged versions of The Phantom of the Opera (1925), It Came from Outer Space (1953), and The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) available for home viewing in 8mm and 16mm versions.

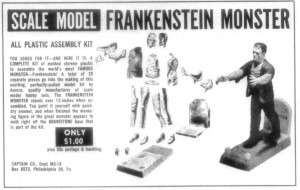

I will return to the range of products featured in FM’s advertising pages later, as part of a larger consideration of the magazine’s content and evolution. But for now I want to focus on an ad that appeared in Issue 18 (July 1962) for the first of what would become a long line of monster kits from Aurora:

Selling for a dollar (plus 35 cents postage and handling) from the newly-formed Captain Company, which operated out of FM’s original home base in Philadelphia, this figure differed from the other products advertised in the magazine in that it wore its DIY nature on its tattered, graveyard-smelling sleeve. A finished and painted version of the kit appears beside an exploded view of its parts, emphasizing rather than eliding the act of construction required to make it whole. Reflecting this, the ad copy trumpets:

YOU ASKED FOR IT — AND HERE IT IS: A COMPLETE KIT of molded styrene plastic to assemble the world’s most FAMOUS MONSTER — Frankenstein! A total of 25 separate pieces go into the making of this exciting, perfectly-scaled model kit by Aurora, quality manufacturer of scale model hobby sets. The FRANKENSTEIN MONSTER stands over 12-inches when assembled. You paint it yourself with quick-dry enamel, and when finished the menacing figure of the great monster appears to walk right off the GRAVESTONE base that is part of this kit.

Taken with the insistent second-person you, the conscious avowal of the kit’s “kit-ness” suggests that, from the start, the appeal of modeling monsters stemmed from its inherently involved and interactive quality: not just activity, but your activity was needed to bring this monster to life. The advertisement hailed readers of FM in a textual foreshadowing of the later “objectual” interpellation promised by the plastic kit itself. In addition, the agency of the reader-cum-builder blurs into that of the creature, which, though a static and nonarticulated figure in its final form, “appears to walk right off” its base. In all, this first appearance of an Aurora kit in FM embodies a nested series of felicitous symmetries, down to the choice of its subject: the Frankenstein Monster, which, in both the Mary Shelley novel that originated it and the 1931 film adaptation that supplied its most iconic rendering, was built from dead parts — an act of promethean “assembly” whose fulcrum is precisely the animate/inanimate divide.

The same principle, of course, could be said to underlie any plastic model kit, whose essence is that it comes in pieces requiring assembly by its owner. Model kits thus metaphorize the object practices of 1960s monster fandom, which similarly took the “pieces” offered by mass culture — in this case, the archive of Universal Studios’ classic horror-film output of the 1930s and 1940s — and transmuted them through a variety of activities into a variety of forms. Significantly, these activities and the forms to which they gave rise often involved movement along what I will call the dimensional axis of media fictions: from printed texts and two-dimensional imagery (both still and moving) into three-dimensional shapes and artifacts. The rubber masks, motorized banks, desktop dioramas, and clay figurines that replicated in the bedrooms and basements of FM readers manifested in material form the texts and images of horror movies and TV shows, enabling fans not just to buy and build, but handle and share, horror culture in tactile form. In turn, these objects often fed back into the production of new texts and images, for example the filming of amateur 8mm monster movies. All of these aspects of horror-media culture came together in Famous Monsters‘ readers, writers, editors, and vendors, and the play of texts and objects that bound and defined them.

In the next installment, I will look more closely at the history of model-kit building as it emerged from hobby, crafting, and collecting cultures in the first half of the twentieth century and, with the introduction of injection-molded plastic kits after World War II, became big business.