Driving home from last night’s screening of Jurassic World, I kept thinking back to a similarly humid summer evening in 1997, when I locked horns with a friend over the merits of an earlier film in the franchise, Jurassic Park: The Lost World. We were lingering outside the theater before heading to our cars, digesting the experience of the movie we had just watched together. He’d disliked The Lost World, which (if I remember his stance accurately) he saw as an empty commercial grab, a cynical attempt by Steven Spielberg to repeat the success of Jurassic Park (1993)—a film we agreed was a masterpiece of blockbuster storytelling and spectacle—but possessing none of the spark and snap of the original. As for my position, all I can reconstruct these 18 years later is that I appreciated The Lost World’s promotion of Ian Malcolm to primary protagonist—after The Fly (1986), any movie that put Jeff Goldblum in the driver’s seat was golden in my book—as well as its audacious final sequence in which a Tyrannosaurus Rex runs rampant through the streets and suburbs of San Diego.

Really what it came down to, though, were two psychological factors, facets of a subjectivity forged in the fantastic fictions and film frames of science-fiction media, my own version of Scott Bukatman’s “terminal identity.” The first, which I associate with my fandom, was that in those days I never backed down from a good disagreement, whether on picayune questions like Kirk versus Picard or loftier matters such as the meaning of the last twenty minutes of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). (Hmm, both of those links go to WhatCulture.com—maybe I should add it to my reading list.)

The second reason for my defense of The Lost World was simply my overriding wish that it not be a piece of crap: that it be, in fact, great. Because even then I could feel the tug of loyalty tying me to an emergent franchise, the sense that I’d signed on for a serial experience that might well stretch into decades, demanding fealty no matter how debased its future installments might become. I hadn’t yet read the work of Jacques Lacan—that would come a couple of years later, when I became a graduate student—but I see now that I was thinking in the futur anterieur, peering back on myself from a fantasized, later point of view: “I will have done …” It’s a twisty trick of temporality, and if I no longer stress about contradictions in my viewing practice the way I once did (following the pleasurable trauma of Abrams’s reboot, I have accepted the death of the Star Trek I grew up with), I am still haunted by a certain anxiety of the unarrived regarding my scholarly predilections and predictions (I’d hate to be the kind of academic whom future historians tsk-ingly agree got things wrong.)

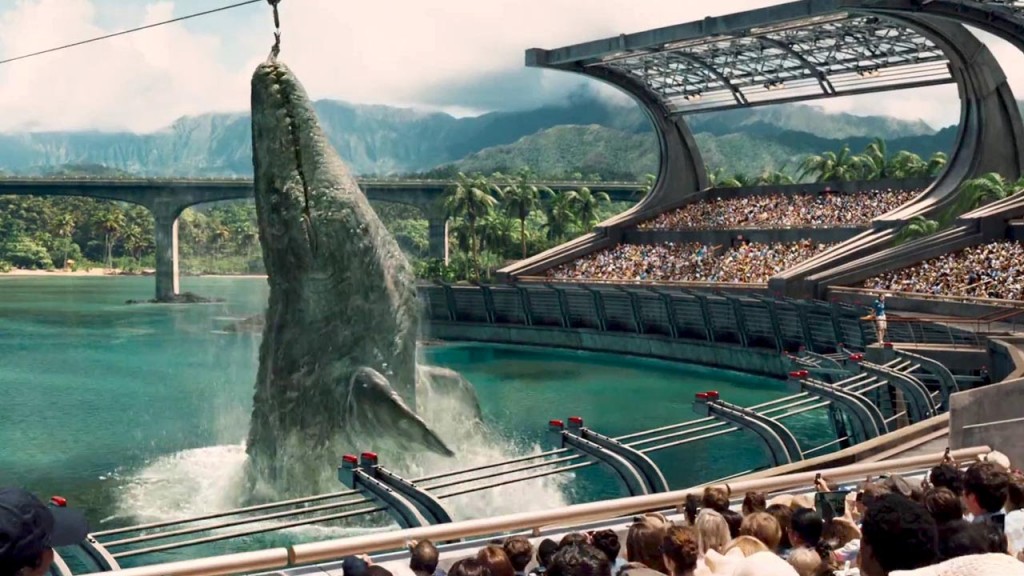

But the tidal pull of the franchise commitment persists, which why I’m having a hard time deciding whether Jurassic World succeeded or sucked. Objectively I’m pretty sure the film is a muddle, certainly worse in its money-grabbing motivations and listless construction than either The Lost World or its follow-up, the copy-of-a-copy Jurassic Park III (2001). Anthony Lane in the New Yorker correctly bisects Jurassic World into two halves, “doggedly dull for the first hour and beefy with basic thrills for most of the second,” to which I’d add that most of that first hour is rushed, graceless, and elliptical to the point of incoherence. One of my favorite movie critics, Walter Chaw of Film Freak Central, damns that ramshackle execution with faint praise, writing: “Jurassic World is Dada. It is anti-art, anti-sense—willfully, defiantly, some would say exuberantly, meaningless. In its feckless anarchy, find mute rebellion against narrative convention. You didn’t come for the story, it says, you came for the set-ups and pay-offs.”

Perhaps Chaw is right, but seeing the preview for this fall’s Bridge of Spies reminded me what an effortless composer of the frame Spielberg can be–an elegance absent from Jurassic World save for one shot, which I’ll get to in a minute–and rewatching the opening minutes of Jurassic Park before tackling this review reminded me how gifted the man is at pacing. In particular, at putting a story’s elements in place: think of the careful build of the first twenty minutes of Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), laying out its globe-jumping puzzle pieces; or of Jaws (1975), as the sleepy beach town of Amity slowly wakes to the horror prowling its waters. Credit too the involvement of the late, great Michael Crichton. His early technothrillers–especially 1969’s The Andromeda Strain and 1973’s Westworld, both of which feed directly into Jurassic Park–might be remembered for their high concepts (and derided for their thin characterizations), but what made him such a perfect collaborator for Spielberg was the clear pleasure he took in building narrative mousetraps, one brief chapter at a time. (Nowadays someone like Dan Brown is probably seen as Crichton’s heir apparent, though I vastly prefer the superb half-SF novels of Daniel Suarez.)

I delve into these influences and inheritances because ancestry and lineage seem to be much on the mind of Jurassic World. DNA and its pandora’s box of wonders/perils have always been a fascination of the Jurassic franchise. In the first film it was mosquitoes in amber; in Jurassic World it’s the 1993 movie that’s being resurrected. Something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue: in front of the camera you’ve got B. D. Wong and a crapload of production design tying the humble beginnings of Isla Nubar to its modern, Disneyesque metastasization, while “behind the scenes” (a phrase I put in scare quotes because, let’s face it, if the material were really meant to stay behind the scenes, we wouldn’t be discussing it), videos like this one work to reassure us of a meaningful connection between the original and its copy:

The “Classic Jurassic Crew” profiled here might seem a little reachy (lead greensman? boom operator?), but the key names are obviously Jack Horner and Phil Tippett, “Paleontology Consultant” and “Dinosaur Consultant” respectively: the former conferring scientific legitimacy upon the proceedings, the latter marking a tie to traditions of special effects that predate the digital. Tippett, of course, made his name in stop-motion animation–the Imperial Walkers in The Empire Strikes Back’s Hoth battle are largely his handiwork–and at first was approached by Spielberg to provide similar animation for Jurassic Park. But when Tippett’s “go motion” technique was superseded by the computer-generated dinosaurs being developed by Dennis Muren, Tippett became a crucial figure, both technologically and rhetorically, in the transition from analog to digital eras. In the words of his Wikipedia entry:

Far from being extinct, Tippett evolved as stop motion animation gave way to Computer-generated imagery or CGI, and because of Phil’s background and understanding of animal movement and behavior, Spielberg kept Tippett on to supervise the animation on 50 dinosaur shots for Jurassic Park.

Tippett’s presence in the film’s promotional field of play thus divulges World’s interest in establishing a certain “real” at the core of its operations, inoculating itself against the argument that it is merely a simulacrum of what came before. It’s a challenge faced by every “reboot event” within the ramifying textualities of a long-running blockbuster franchise, forced by marketplace demands to periodically reinvent itself while (and this is the trick) preserving the recognizable essence that made its forerunner(s) successful. In the case of Jurassic World, that pressure surfaces symptomatically in the discourse around the movie’s visual effects–albeit in a fashion that ironically inverts the test Jurassic Park met and mastered all those years ago. Park’s dinosaurs were sold as breakthroughs in CGI, notwithstanding the brevity of their actual appearance: of the movie’s 127-minute running time, only six contained digital elements, with the rest of the creature performances supplied by Tippett’s animation and Stan Winston’s animatronics. Those old-school techniques were largely elided in the attention given to Park’s cutting-edge computer graphics.

Jurassic World, by contrast, arrives long after the end of what Michele Pierson has called CGI’s “wonder years”; inured to Hollywood’s production of digital spectacle by its sheer superfluity, audiences now seek the opposite lure, the promise of something solid, profilmic, touchable. This explains the final person featured in the video: John Rosengrant of the fittingly-named Legacy Effects, seen operating a dying apatosaurus in one of Jurassic World’s few languid moments. The dinosaur in that scene is a token of the analog era, offered up as emblem of a practical-effects integrity the filmmakers hope will generalize to their entire project. It’s an increasingly common move among makers of fantastic media, one that critics, like this writer for Grantland, are all too happy to reinforce:

J. J. Abrams got a big cheer at the recent Star Wars Celebration Anaheim when he said he was committed to practical effects. George Miller won plaudits for sticking real trucks in the desert in Mad Max: Fury Road. Similarly, [Jurassic World director Colin] Trevorrow gestured to the Precambrian world of special effects by filling his movie with rubber dinos, an old View-Master, and going to the mat to force Universal to pony up for an animatronic apatosaurus. Chris Pratt’s Owen Grady tenderly ministers to the old girl before her death — a symbolic death of the practical effect under the rampage of CGI.

I hope to say more about this phenomenon, in which the digital camouflages itself in a lost analog authenticity, in a future post. For now I will simply note that “Chris Pratt’s Owen Grady” might be the most real thing within Jurassic World. Pratt’s performance here is strikingly different from the jokester he played so winningly in Guardians of the Galaxy: he’s tougher, harsher, more brutish. Spielberg is rumored to want him to play Indiana Jones, and I can see how that would work: like the young Harrison Ford, Pratt can convincingly anchor a fantasy scenario without seeming like’s playing dress-up. But the actor Pratt reminds me of even more than Harrison Ford is John Wayne: his first shot in Jurassic World, dazzlingly silhouetted against sunlight, recalls that introductory dolly in Stagecoach (1939) when the camera rushes up to Wayne’s face as though helpless to resist his primordial photogenie.

As for the rest of Jurassic World, I enjoyed some of it and endured most of it, borne along by the movie’s fitful but generally successful invocations of the 1993 original. “Assets” are one of the screenplay’s keywords, and they apply not only to the dinosaurs that are Isla Nubar’s central attractions but to the swarm of intellectual property that constitutes the franchise’s brand: the logos, the score, the velociraptors’ screeches and the T-Rex’s roar. (Sound libraries, like genetically-engineered dinosaurs, are constructed and owned things too.) Anthony Lane jeers that there is “something craven and constricting in the attitude of the new film to the old,” but I found the opposite: it’s when World is most clearly conscious of Park that it works the best, which is probably why I enjoyed its final half an hour–built, as in Park, as an escalating series of action beats, culminating in a satisfying final showdown–the most.

But that might just be my franchise loyalty talking again. As with The Lost World in that 1997 argument outside the theater, I may be talking myself into liking something not because of its actual qualities, but because it’s part of my history–my identity.

It’s in my DNA.

Brilliantly put. Especially interesting is the work of the shameless “behind the scenes” videos like the one you embedded; I feel like John Caldwell would have something to say about the insincerity of those kinds of industrial texts…

My experience was, I suspect, similar to yours. I just came home from seeing _World_, and walked away from it feelingly like my $10.50 netted me a pleasant jolt of nostalgia (albeit in perhaps a more diluted way than when I went to the midnight screening of the _Park_ 3D rerelease). I think the use of the _Park_ audio library was especially effective in that regard; there’s something triggering (in a positive way) about hearing an instantly recognizable sound that you associate strongly with something you like a lot: the T-rex bellow and the velociraptor chirps come to mind here. (As does, for that matter, the use of the Macintosh startup chime in Wall-E.) I was even, mostly, able to forgive the kinda slapdash opening act, because seeing dinosaurs in 3D is still cool, even if those dinosaurs aren’t doing very much of interest.

Like a handful of other viewers (http://www.ifc.com/fix/2015/06/jurassic-world-doesnt-deserve-cla), though, lost my patience with the film around its portrayal of gender. Where the dyad of Laura Dern’s “tenacious” Ellie and Jeff Goldblum’s moderately sleazy Malcolm showed a compelling push-pull between equals, I found myself mostly disgusted with Pratt’s character. At least one of the film’s writers was aware of the, ahem, obvious problems of workplace impropriety when they included the “I have a boyfriend” interaction in the control room… but apparently that deft hand didn’t extend to the rest of the script.

Yoel, thanks so much for these spot-on observations. John T. Caldwell and other writers in the production-studies tradition have done a lot to awaken me to (and sharpen my critical eye toward) the promotional discourses in which special effects circulate and become objects of contemplation. In fact, I now see the sharing of such behind-the-scenes knowledges as essential to any definition of special and visual effects–which must be seen as technological performances married to controlled acts of public disclosure, with all the ideological and industry-friendly framing that implies.

Yeah, I stayed away from discussing World‘s gender politics in this post, but not because I don’t think they’re significant; on the contrary, the discussion around the characterization of Owen and Claire, the way their roles are inhabited by Pratt and Bryce Dallas Howard, and their direction by Colin Trevorrow (whose defense that he was going for a classical-Hollywoodesque screwball comedy dynamic seems questionable at best) has been one of the most fascinating aspects of the film’s reception. I’m so grateful to Joss Whedon for calling out the problematic on Twitter!

I’d like to delve into those issues in a future post, maybe the overdue one where I round up some of the summer’s other SF films, including the very gender-interested Ex Machina and Mad Max: Fury Road. I think what I was trying to get at in this review was my shock at my own positive reaction to Pratt’s otherwise repellent Grady; I found myself gravitating to his persona the way I also respond to the screen masculinities of John Wayne, Humphrey Bogart, Gary Cooper, even Charlton Heston–sour, unkind, inexpressive icons, yet powerful to me in a totemic way I can’t fully articulate. Daddy issues, I suppose.