[This is the second of four posts counting down the final episodes of Battlestar Galactica. To see the other entries, click here.]

I suggested in last week’s Galactica post that viewing the conclusion of a series “live” — that is, at the juncture of its initial broadcast — is more like witnessing than watching: there is a ritualistic, communal aura to the process, a kind of terrible necessary togetherness. The point is simply to be present, sharing breath with other viewers (even if they exist only as an extrapolated throng beyond the darkened chamber of my living room). And present, of course, with the show itself as it spins its final variations on a theme, its last acts of parole from a lovingly-established langue. In this sense, being with a series as it draws to a close is something like hospice.

In the case of BSG, though, watching live has its drawbacks. Namely, the commercial breaks, inescapable symptom of advertiser-supported TV and part of its formal DNA (funny how impossible it is to imagine BSG or other good shows minus the structuring aporia and epiphany of teasers, acts, cliffhangers, and recaps imposed by a combo of serialization and the need to hawk Hummers and Taco Bell’s Fourthmeal). The DVR lets me skip easily enough past these brightly-lit, tone-deaf ruptures in Galactica‘s noir sensibility, but I have a harder time ignoring the SciFi Channel’s own promotional appeals to fandom: they’re selling off parts of the show, whether through online auctions of production materials or through items of dubious diegetic appropriateness such as the Battlestar Galactica Black Cylon Toaster.

I know, I know: as a professional nerd who divides his loyalties between Star Trek and Star Wars, the marketing of my own passions back to me should have long ago lost its power to scandalize. But there’s something uniquely crass about the avid dispatch with which the fantasy world of BSG is being carved up and sold for scrap. If we are indeed sitting with a friend who’s slipping away, these ads are like someone knocking on the window, asking how much we want for the furniture.

There’s a neat symmetry, though, to the idea of BSG (the show) coming apart at the seams and the way this mirrors the fragmentation of Galactica “herself” — that battered warship under the command of William Adama, cracks opening in her hull as a result of too many FTL jumps and near-fatal encounters with nuclear warheads and Basestar missile volleys. (In my next post, I’ll have more to say about my favorite part of the reimagined BSG, its awesome space battles.) More to the point, being indignant about someone making money off BSG ignores the truth at the heart of its franchising: it’s always been about the bucks, baby. Glen Larson conceived BSG back in the late 1970s as a televisual answer to that redefining juggernaut of science-fiction media, Star Wars, and in this sense the show has been cashing in from the very start.

The years between (what we would eventually come to know as) A New Hope in 1977 and The Empire Strikes Back in 1980 seemed like an eternity to me; during that period I went from being 11 to 14 years old, and in retrospect I didn’t know how good I had it. Teenage turbulence and Ronald Reagan hadn’t yet pounced on either my own body or the body politic; each year brought new releases of films (Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Superman, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Alien) that have since become load-bearing members of my imaginary; yet I was ever hungry for more. Battlestar Galactica premiered on September 17, 1978 on ABC, a network that had already demonstrated to this young viewer that it could do no wrong with Charlie’s Angels and The Six Million Dollar Man.

My excitement about the first BSG had little to do with its characters, who seemed like cookie-cutter TV types (I blame Lorne Greene’s Adama, who carried an overpowering intertextual odor of Bonanza everywhere he went; years later I would realize, with Firefly and Serenity, that I don’t like westerns in my science-fiction peanut butter, no matter how structurally compatible the two genres may be). BSG’s storyline was similarly uninspiring: I’ve never cared for Gilligan’s Island-style narratives in which a group of characters search desperately for home. Perhaps because the Colonials’ psychological and existential state approximated too closely my own preadolescent anxieties about school that led me to fetishize the comfort and familiarity of home, I preferred the manifest-destinied explorations of Star Trek. Better to boldly go than to run scared; better to launch a wagon train to the stars than to circle the wagons and pray for survival. (Ironic, then, that several series later, Voyager would fall into the same delayed-gratification trap of a constantly thwarted quest for earth.)

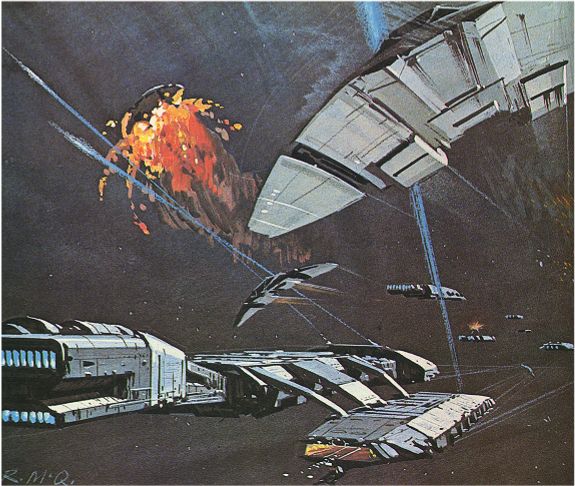

Instead, I was infatuated with BSG’s world and the props and visual effects that constituted it. The Battlestar, its “ragtag fleet,” the fighter-jet Vipers and manta-ray Cylon Raiders, all existed in three separate yet indivisible frameworks, like water in solid, liquid, and gaseous phases: there were the ships in their diegetic reality, composited against starry backgrounds and lit with rotoscoped laser beams; the detailed miniatures I knew had been built in some FX house’s model shop, affixed to neon pylons and photographed against blue screens by a motion-controlled camera that tracked, tilted, and panned while the ships themselves remained stationary; and finally, replicated in my own bedroom, plastic model kits glued together with Testor’s hallucination-inducing goo, smeared with paint from tiny square glass jars. My models possessed less detail than the studio versions but were enormously more powerful in their totemic aura: localized, three-dimensional concretizations of the vast immaterial universe that was in part BSG’s production design and in part the mental system those designs organized, my own (possibly glue-enhanced) hallucinations.

The appeal of BSG’s universe faded somewhat as the series went on, I suppose because the heavily-repeated FX shots began to be outweighed by the narrative’s predictable and uninspired plotting. My sense of wonder has always worked better in two-hour chunks than in the twenty-odd hourly helpings of a television season: I can watch Logan’s Run over and over in motion-picture form, but was never engaged by the serial incarnation that ran on CBS from 1977 to 1978. This hypothesis was proven for me in 1979, when BSG’s two-hour pilot was released theatrically. I went to see it several times in matinees at the Campus Theater in Ann Arbor, holding my arms (sunburned and peeling from a canoe trip on the Huron River) stiffly in front of me. Projected on a huge screen with all commercials excised, the opening hours of BSG — its primal scene of civilization and military order knocked permanently akimbo by sneak attack — regained the mythic resonance Glen Larson had always intended them to have, a resonance channeled from Pearl Harbor by way of Star Wars. By that time I’d learned from the invaluable resource Starlog that Ralph McQuarrie and John Dykstra, artists responsible for so much of Star Wars‘s texture and text, had worked on BSG, and that the pleasure I took from the series was in fact a complex echo (and, undeniably, a dilution) of a purer, prior signal. At 13, my first encounter with nostalgia, fittingly motivated by texts themselves obsessed with lost golden ages.

No matter: in those hours of BSG’s reencounter I discovered a truth about stories and special effects: they can be recycled, revisited, and reinvented without harm. Whether in the replaying of videotapes and DVDs, the sequelization of movies, the serial sinewaves of TV narrative, or the radial expansions of transmedia, there is always more to be had — more to be discovered, judged, dismissed or cherished. It’s what gives me hope that our current Battlestar Galactica will not be the last; that what has happened before will (always) happen again.

[Next week’s post will turn to Zoic, the visual-effects house responsible for much of Galactica‘s signature visualization and logics of action.]

How could anyone possibly doubt the appropriateness, diegetic or otherwise, of a Cylon-themed toaster that burns “Frak off” onto your toast? I want one, and I’ve never even seen the show.

Mike, while your comment might make some diehard BSG fans grind their teeth, I appreciated it — in plain fact, I hadn’t looked closely enough at the tie-in toaster to realize its range of capabilities. And considering that I own a Red Dwarf coffee mug that says “Smeg Off,” I’m hardly one to lecture others!

For some reason, I’m not nearly as offended by the sale of BSG toasters or t-shirts/coffee mugs/posters/baby outfits emblazoned with the word “frak” as I am by the auctioning off of props from the show.

Particularly, when I first saw the advertisement for the sale of Caprica 6’s red dress (which has come to be one of the true icons of the show, at least if its prominence on the DVD boxes for seasons 1-3 indicates anything), I couldn’t help but think, in rapid succession: (1) “That’s pretty cool.. you can own the red dress and pretend that you’re one of Gaius Balthar’s hallucinations!”; and (2) “There’s something wrong with that. It’s Caprica 6’s dress, not some fanboy’s collector’s item.”

We’re in agreement on this one, Yoel. It’s like TPTB have short-circuited the normal process by which production materials circulate to fans through casual networks.