As my attention shifts to one of the major goals of the summer — drafting a proposal for my book on special and visual effects — I’ve started to augment my movie-a-day habit with some classic FX titles. These are films I’ve seen before, in some cases many times, but which need revisiting. Seeing them now can be a corrective shock, revealing my memory for the sloppy generalizing mechanism it is. Impressions of movies watched in childhood blend together, in the adult mind, like ingredients of a stew, a delicious melange that is nevertheless a kind of monotaste: a tidy averaging of visual and narrative pleasures that, with a fresh viewing, shatter back into discrete components. The movie again becomes a complex terrain rather than a distant map, a succession of contrasting images rather than a single iconic poster still, a cascade of rediscovered characters, tableaux, action setpieces, and lines of dialogue. It’s like opening a box of forgotten photographs.

In the case of Planet of the Apes — Franklin J. Schaffner’s 1968 original, not Tim Burton’s lousy 2001 remake — I was stunned to find a film far more stark, confident, somber, chilling, and stylish than the simplistic caricature to which I’d reduced it. My first encounter with Planet of the Apes came sometime in the mid-1970s, when it ran as part of “Ape Week” on our local ABC affiliate’s Four-O’Clock Movie. I’d get home from school in time to watch an hour or so of cartoons before the feature came on; Ape Week was just one of several themed lineups I looked forward to eagerly, including “James Bond Week” and “Monster Week” (a string of Eiji Tsuburaya‘s Godzilla and Mothra movies).

The Apes series was a perfect fit for the Four-O’Clock Movie because there was one for every day of the week: from Monday’s installment of the first film through Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970) on Tuesday, Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971) on Wednesday, Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (1972) on Thursday, and Battle for the Planet of the Apes (1973) on Friday. The end of the week didn’t mean an end to Apes, though. Right about that time, a live-action TV series aired, followed by an animated counterpart on Saturday mornings. It would be thirty years before I heard the term transmedia franchise, but — along with daily reruns of the original Star Trek series — Apes was my inaugural passport to the labyrinthine landscape of distributed science-fiction storyworlds.

What I loved about Planet of the Apes back then, and what has stayed with me over the years, can be summarized in two images that sent me into an ecstasy of eeriness: the ape makeup created by Ben Nye and implemented by John Chambers; and the famous final shot, in which the hero Taylor (Charlton Heston) stumbles across the ruins of the Statue of Liberty and realizes he’s been on Earth — not an alien world, but his own home — all this time. The frame is below; a grainy YouTube version can be found here.

It’s one of the great twist endings in SF — contributed, fittingly enough, by Rod Serling. But its unfortunate effect was to instantly reduce the movie to a grand cliche, a semiotic Shrinky-Dink, source of endless quotations and parodies in the decades that followed. The sad truth about twist endings is that they follow a logic opposite that of genre (in which the same patterns reappear over and over again without anyone taking offense; we applaud them, in fact, for their iterative familiarity): once given its Big Reveal, a twist shrivels on the vine, spoiled by critics, lampooned for its very memorability. Citizen Kane‘s Rosebud, The Sixth Sense‘s dead psychiatrist, St. Elsewhere‘s world-in-a-snowglobe — each exists, like Taylor’s final, horrible epiphany, as the ultimate self-annihilating closure, shutting down not just a particular narrative instance, but the possibility of its own resurrection in anything but smirkily insincere form. Shots like the one that concludes Planet of the Apes are, to me, a perfect example of Lacanian captation: they arrest and hold us in an escape-proof hermetic prison of the imaginary.

OK, psychoanalytic blather aside, what was so great about watching Planet of the Apes again? I suppose my answer is yet more Lacan, for both the apes and humans are trapped by and within their own misrecognitions. Taylor and his fellow astronauts firmly believe themselves to be on an alien planet, despite evidence to the contrary (the apes speak English); for their part, the apes see the humans as completely Other and cannot countenance any notion that there is an evolutionary link between them. It’s a comedy of evolutionary errors, the Scopes Trial replayed simultaneously as farce and deadpan drama. The truth of the situation is hidden, like the purloined letter, in plain sight; it is not until the end, in a traumatic confrontation with the Real, that Taylor traverses his fantasy. (Maybe that’s why the joke has been replayed so frequently in pop culture, from Spaceballs to The Simpsons; what is repetition but the insistent revisiting of trauma?) Of course, as often occurs in science fiction, the meta-misrecognition that operates here is failing to see in the portrayal of a “future” the actual representation of a “present.” Eric Greene’s Planet of the Apes as American Myth explores this aspect of the film and its sequels, arguing that Apes is a funhouse mirror held up to racial politics in the United States.

Bringing this all back home to the movie and its special effects, I see two kinds of misrecognition at play in the visuals, both of them integral to the suspension of disbelief by astronauts, apes, and audiences alike. First, of course, are the actual human beings (Roddy McDowell, Kim Hunter, Maurice Evans) beneath the prosthetics and hair appliances. The makeup and costumes that turn these actors into sentient, speaking apes do not mask or muffle the performances, but rather estrange and amplify them: we watch and listen for nuances of emotion, an amused glint in the eye, a subtle shift in intonation, precisely because they are cloaked in filmmaking technology. At first glance the masquerade is comical, almost grotesque, but it quickly gives way to some remarkably graceful performances. Our twinned awareness of the trickery and investment in the fantasy reflects the knife-edge calibration of disbelief attending the finest FX work.

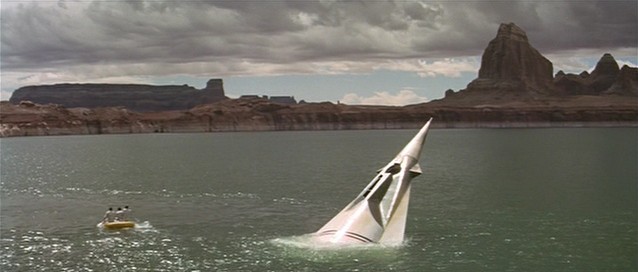

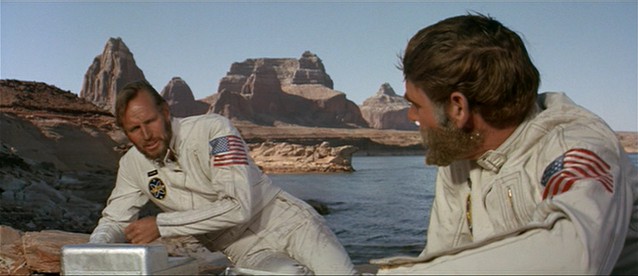

But there’s a second register of misrecognition here, one I would have missed completely if I hadn’t been watching a pristine widescreen transfer of the film. The first act of Planet of the Apes consists of Taylor and his fellow astronauts trekking across the forbidding but beautiful scenery of Arizona and Utah — in particular, the area of the Colorado River known as Lake Powell:

I was dumbstruck by this natural backdrop of mountains, deserts, and water, as gorgeously alien as anything in Nicolas Roeg’s Walkabout (1971). It occurred to me that the genius of this portion of the movie — an opening thirty minutes before the apes even show up — is that it places the spectator in a homologous position to the stranded astronauts. Like them, we stare at a world that is at once ours and another’s; a landscape both earthly and unearthly. Like the ape makeup, the cinematography forces us into sublime attentiveness, consuming every detail of a setting made familiar by our experience with terrestrial features, then unfamiliar through a storyline that presents it as an alien world, then familiar again in the final beachside revelation.

I guess what I’m saying with all this is that Planet of the Apes stands out to me as much for its planet as for its apes; and that in both constructs (and our response to them) we glimpse something of the multitiered, shuttling structure of belief and disavowal that great special effects provoke.