It’s not hard to see what Doug Liman intended Jumper (2008) to be: a slick, stylish action-adventure, paced to the quick rhythm of its protagonist’s wormhole-assisted leaps through space. In terms of emotional tone, something a bit less serious than The Bourne Identity (2002) and more serious than Mr. and Mrs. Smith (2005), with a touch of the structural experimentation of 1999’s Go (probably my favorite of Liman’s movies, even over Swingers [1996], which, while funny, bared its brand of prefab indie classic a little too emphatically).

But Jumper turns out to be an anemic misfire, its frictionless construction (which might, during preproduction, have seemed a strength) resulting in something like those Olestra Doritos I used to eat: tasty, low in calories, and passing with liquid brevity through the digestive system. Or — a better metaphor — like David Rice (Hayden Christiansen) himself, a young man who through some never-explained and never-sweated mutation of genetics, neurochemistry, or both, can teleport instantly from one place on earth to another. Building a plot around a person unbound by basic physical laws is always risky. First, there’s the problem of identification: truly super superbeings are impossible to empathize with, a notion explored brilliantly through the figure of Doctor Manhattan in Alan Moore’s Watchmen. Second, it’s hard to embed super-powerful beings in dramatic situations that offer any real challenge or suspense. Think of the “burly brawl” in The Matrix Revolutions (2003): Neo’s hyperkungfu turned his showdown with hundreds of Agent Smiths into an inadvertantly funny dance number, spectacular in the manner of Busby Berkeley musicals and charming in the manner of Buster Keaton slapstick — but never exciting, because nothing was at stake.

To get around this dilemma, our fantasies of superpower have yoked the anomalous beings at their center to various forms of existential and psychological ennui. DC got it right with Superman and Batman, both orphans, one an extraterrestrial “stranger in a strange land” and one a PTSD-afflicted vigilante. Superman’s love for Lois Lane is ultimately a hobbling force, locking him to a human scale of emotions and practical concerns (why else would he need to take a 9-5 job at the Daily Planet?). In literature, Billy Pilgrim — the haunted hero of Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five (1969) — travels through time, but not under his own direction; instead he revisits traumatic moments of war and family life, adrift in a temporal ocean. (A similar theme organizes the lovely, tearjerking tapestry of Audrey Niffenegger’s 2003 novel The Time Traveler’s Wife.)

Jumper would have been more interesting if David’s teleporting ability took him only to places where he’d fallen in love or feared for his life — or if he compulsively returned to the same locations over and over, without meaning to: a Freudian trip. The film’s mystery might then have resonated as much inwardly as outwardly. As it is, the situation with which the screenwriters have saddled David, and us, is both needlessly elaborate and absurdly simplistic. Bad guys called Paladins hunt those who can teleport, using a range of electrified devices (again, both baroque and silly in their design) to anchor, trap, and ultimately kill the jumpers. It may not be a sin that the Paladins’ motivation isn’t explained in more detail — the opening crawl of Star Wars taught a generation of filmgoers the value of ruthlessly boiling down exposition — but it would have been nice to learn even a little bit about how their “civil war” with the jumpers has played out over history. (Since jumpers must use images to target their more exotic jumps, how would they have functioned in a pre-photographic era?)

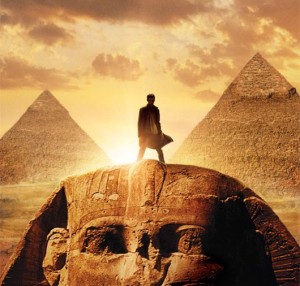

Ah well. The film is more interested in portraying David as a kind of supertourist, someone who can go wherever he wants, whenever he wants — enjoying a picnic atop the head of the Sphinx, followed by surfing in Thailand. This has the effect of equating teleportation with ownership of a really good credit card, a consumerist fantasy of total access and freedom. A shame, because the charm of Steven Gould’s 1992 source novel is in showing how David learns his way gradually into his power, staged as a series of plausibly awkward experiments and epiphanies. The book, that is, eases us into a superhuman life by showing us each incremental point on the hero’s journey. The movie, by contrast, skips all that — “jumps” past it — giving us a protagonist who seems petulant rather than plaintive, arrogant rather than awesome. (The fact that he is played by the same piece of plastic who sank the Star Wars prequels doesn’t help.)

Liman’s comments to the contrary, Jumper is very much a visual-effects film; the teleportation effect is as much the movie star as Christiansen. According to the DVD extras (and here’s a tip: if the FX get their own doc, there’s a safe bet the picture was bankrolled on the basis of them), considerable R&D went into getting the jumps just right. Wikipedia records over 100 jumps in the film, each subtly adjusted to reflect distance and emotional state of the jumper. The effect itself is really a package of techniques. Characters appear and disappear in a swirl of particles, as though they’ve turned into ash and blown away; the local environment is stirred as though in a strong wind, papers fluttering, doors slamming; and hazy, prismatic “jump scars” remain in their wake, marking the point at which spacetime has conveniently ruptured. Often all of this is accompanied by offhand flicks of the camera, as though following the body’s transit through hyperspace; a shot might begin with a quick pan downward to street level, an instant before the jumper appears.

For the most part, we witness jumps from the “outside,” that is, with a body popping out of and back into presence without traveling the intervening distance. (Some of the most pleasing instances are long, motion-controlled takes in which a body — or car! — might appear five or six times, dancing from spot to spot in the frame.) But every once in a while, the camera goes virtual and follows David through a jump, as in the example below, in which he shifts himself from an icy lake to a local library:

All this jumping about is undeniably fun, a kind of cat-and-mouse in which each leap arrives slightly before or after the audience predicts. It looks stylish, as though the jumpers are being sucked away by concealed vacuums. But ultimately, it doesn’t add up to anything more than itself: in an act of accidental self-referentiality, Jumper the movie is a movie that Jumps, and that’s all.

Hey Bob, sorry I haven’t responded for a while. Jumper holds a very dubious honor for me, though: it’s one of the first films I’ve stopped in a long, long time. I was watching it on a plane, and ended up thinking that I was enjoying sitting looking into space better than looking at this film. It seemed to try to be funky by approximating the feeling of jumping with its own editing and plot, and with Hayden Christiansen having attended the Keanu School of Acting, I needed the film around him to do a little more. Your suggested edits all sound like a much better film — pity that your 1000 words or so proved considerably more intelligent than the combined “talents” of the Jumper production staff 😉