The opening act of the summer movie season, Iron Man, is much like the machine armor worn by Tony Stark (Robert Downey Jr.): a potent blend of advanced technology, sleek style, and glowing energy. The fetishism of the super-suit has rarely been quite so explicitly rendered, or embraced with such pornographic shamelessness, in comic-book cinema. Sure, movies and television have given us plenty of heroes whose iconic power resides in the costume (whether caped or capeless): Christopher Reeve’s Superman, Tobey Maguire’s Spider-Man, the leather-overcoat-and-sunglasses combo of Wesley Snipes in Blade, the patriotic bustier worn by Lynda Carter as Wonder Woman. Often these sartorial choices become flashpoints of controversy with fans: think of Bryan Singer’s X-Men adaptation, which did away with the classic yellow costumes of the comic series, or the many nippled and sculpted variations of the Batsuit worn by the Batactors playing a series of Batmen in the Batfranchise.

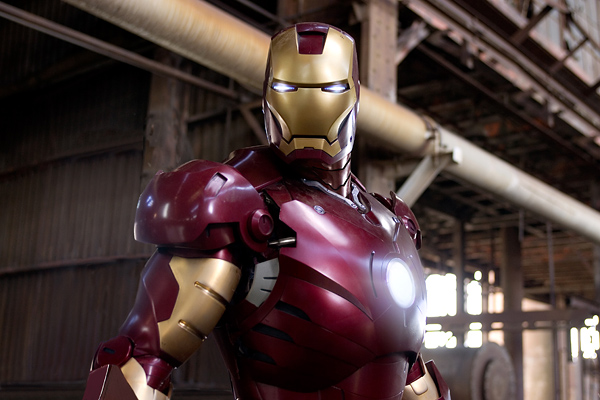

In Iron Man, the situation is different, for Iron Man is his suit, the “secret identity” within a compromised figure both morally and physically. Over the course of the story, Stark’s transformation from a hard-partying weapons magnate to a passionately peace-committed and (mostly) teetotaling cyborg is made concrete — made metal, really — through the metaphor of the successively more sophisticated armor shells in which he encases himself. The first is a kitbashed monstrosity the color of corroded tin cans, crisscrossed with scars of solder. Like a rustbucket car, it survives just long enough to convey Stark to version two, a more compact silver exoskeleton reminiscent of Ginsu knives and Brookstone gadgets. It’s quite satisfying when Stark arrives at the canonical configuration, a red-and-gold chassis of interlocking plates, purring hydraulics, and HUD graphics that answers the question “What would it be like to wear a Lamborghini?”

What’s clever is how these upgrades express Stark’s ethical evolution while recapitulating decades of shifting design in the Marvel comic series from which this movie sprang. (It’s kind of like a He’s Not There version of James Bond in which the lead is played over the course of the film by Sean Connery, then Roger Moore, followed by Timothy Dalton, Pierce Brosnan, and Daniel Craig — with a quick dream interlude, of course, starring George Lazenby.) Iron Man, in other words, manages to honor superhero history rather than pillaging it, and this — along with the film’s smart screenplay and glossy digital mise-en-scene — wins it a sure place in future best-of lists when it comes to the spotty genre of comic-book adaptations.

Another weapon in the film’s arsenal, riding within in its narrative delivery system like he pilots his mechanical costume, is Robert Downey Jr., who seems to have arrived at a point of perfect intertextual harmony with this turn in his career. His performance as Stark is properly lived-in and mischievous (indeed, the actor’s persona is yet another kind of suit, this one built of bad publicity) yet alive with disarmingly sincere warmth. In one of the film’s facile yet pitch-perfect tropes, Stark must wear a pulsing blue-and-white generator on his chest, a kind of electromagnetic pacemaker that doubles as an energy source for his armor and trebles as a signifier of the character’s humanity. Downey Jr. is himself a kind of power source that propels the vehicle of Iron Man forward while lending it, in stray moments, genuine moral weight. His portrayal reminds us that, while a superhero’s technological or organic essence is important, the larger ingredient is something harder to quantify and calibrate — in Stark’s case, a kludge of intellect, imagination, and compassion that easily trades one outfit for another.

That’s not all that’s going on under the hood: the fight scenes, not to mention flight scenes, are awesome, and Jeff Bridges is remarkably menacing with all his hair relocated from his head to his chin. There’s some nimble ideological shadowboxing around the the military-industrial complex and the terrible allure of “shock and awe” (there’s your real pornography). And while Stan Lee makes his trademarked cameo, branding this as yet another item in Marvel’s transmedia catalog, a quirky counterpoint is sounded when a villain taunts Stark by asking “Did you really think that just because you had an idea, it belongs to you?” For comic fans, it’s hard not to hear this and think of Marvel’s infamous screwing of Jack Kirby. At the same time, we should count our blessings that concepts like Iron Man travel so fluidly through our mediascape, rephrasing themselves in the transformational grammar of convergence cinema. Too often, the result is an ugly and lifeless thing — a strangled fragment like Daredevil, a run-on sentence like Van Helsing. But once in a lucky while, you get a perfect little poem like Iron Man.

“A perfect little poem”–now I’m even more bummed that I didn’t get to see it Thursday night. Kids and finals have a way of getting between me and geeky pleasures.

Yeah. For some reason, that quote about “ideas” from “OB” Stane was the thing that stuck with me most in the film — not that I didn’t feel the rest of it wasn’t amazingly well done, equally reverential and inspired. And always been a personal fan of Downey, Jr. — great to see him find a role that fits him like a glove, and now get press for his true talents.

Another Sunday $2.50 show, another late response to your blog…

Saw this last night. I thought it was a hoot, and I don’t much like comic-book superhero adaptations.

Not much to add to or subtract from the above. I’ll just mention that I enjoyed the adroit use of relevant tunes: the theme from the old TV cartoon, that punk tune from the _Repo Man_ soundtrack, and of course, the eponymous Black Sabbath classic. It was easy to predict that that last one would cover the closing credits, but the segue into it was a nice touch in a film full of nice touches.

On a philosophical note, I sort of agree with the bad guy about the ownership of ideas, in a way. From those to whom much is given, much is demanded.